A remarkable true story of enterprise and espionage, of mystery and mayhem, in the Far East

Jim Thompson was the best-known western businessman in Thailand, arguably the best known in all of Southeast Asia. Then one day, during a brief holiday in the highlands of Malaysia, he simply vanished — and became famous round the world for his mysterious disappearance. The military and civil authorities of three countries carried out extensive searches and investigations. They were aided or hindered by Thompson’s family and friends, professional trackers, helicopter pilots, local tribal peoples, a squad of Ghurkhas, an assortment of soothsayers and mystics (one of them a Jesuit brother), and the usual crowd of busybodies and reward-hunters — all of them egged on by such powerful forces as Time magazine. Almost as soon as he went missing, crackpots and publicity-seekers would report sighting Mr. Thompson in bizarre locations, just as people would do with respect to Elvis Presley a decade later.

No one has ever proved what happened to Mr. Thompson (who, after seven years, was declared legally dead in 1974). Right from the beginning, however, there have been many competing theories, which continue to be reflected in the ongoing stream of literature on the subject. Some believe Mr. Thompson, who was known as the Thai Silk King for the way he made a fortune invigorating the country’s silk industry beginning in the late 1940s, was kidnapped by Chinese gangsters, even though no ransom demand was ever received. Still others argue he was captured, and presumably killed, by one or another Thai political faction, for the victim was deeply involved in the inner-workings of that coup-prone nation. In his 1970 book Bangkok: The Story of a City, the English novelist Alec Waugh (elder brother of the more prominent Evelyn) summarized the numerous theories without voting for any, though between the lines he seemed to express sympathy with Time’s predictable view that communists were behind it all.

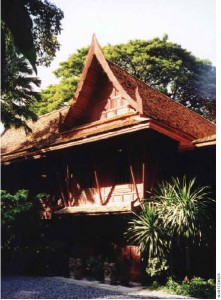

The most prolific writer on the subject, and in stylistic terms the most pleasing, is William Warren, the elder statesman of the conspicuously large community of expat English-language authors in Bangkok and a true gentleman known to all. He first met Jim Thompson on arriving in Bangkok in 1959 and has written about him frequently in such books as The Jim Thompson House (US$20) and, more recently, At the Table of Jim Thompson (ditto). The former concerns one of Bangkok’s most visited landmarks, the extraordinary canal-side residence that Mr. Thompson constructed for himself and his collection of Asian art by reassembling and joining together five traditional teak houses taken from the ancient capital of Ayutthaya. The latter work deals with the chain of three high-end Bangkok restaurants that strive to recreate the cuisine that Mr. Thompson, a compulsive and convivial host, served to guests. Both are published in Singapore by Archipelago Press.

So too is Jim Thompson: The Unsolved Mystery (US$12.50), first released in 1969 and revised several times since then. In it, Mr. Warren recalls his friendship with the book’s subject and weighs the numerous theories. In the end, he concludes that Mr. Thompson either perished in some accident or else committed suicide (for his personal and professional lives were often at hazard with the sunny urbane face he showed the public). Mr. Warren doesn’t dignify the pet theory of another often-reprinted work, Solved! The “Mysterious” Disappearance of Jim Thompson, the Legendary Thai Silk King (Word Association Publishers, US$10.95). Solved! is the work of Edward Roy De Souza, a rather odd Singaporean prose stylist indeed, who believes that Mr. Thompson was murdered because he was using the internationally regarded Jim Thompson Thai Silk Company as a front for drug trafficking. Of course, that’s not to dismiss the suggestion that Mr. Thompson had what might be called interesting friends. That was never a secret. Yet it is only now that we have a book that soberly assembles pieces of the jigsaw puzzle, including many not previously known to us: The Ideal Man: The Tragedy of Jim Thompson and the American Way of War by Joshua Kurlantzick (John Wiley & Sons Canada, $30.95).

James Harrison Wilson Thompson, born in 1906 and trained as an architect, was an American aristocrat who grew up in Delaware with people named Rockefeller and du Pont. His maternal grandfather was a Union general in the American Civil War who, interestingly, entertained members of Siam’s royal family when they visited the U.S. In the Second World War, Jim Thompson was recruited into the Office of the Strategic Services by its aptly named leader, Wild Bill Donovan. He served first in Europe, once parachuting into France behind the German lines to blow up bridges. Later he was sent to Thailand, where he helped organize the Free Thai resistance movement against the Japanese, who had been welcomed by Thailand’s ruler, Field Marshall Phibul (that is, Phibul Songkhram, but known by his forename alone, as is Thai practice). After V-J Day, Mr. Thompson remained in Bangkok, spying for the U.S. government despite his evolving sympathy for those whom Washington, for all its anti-colonialist rhetoric, most feared: the nationalist insurgents not only in Thailand but also in the French territories of Laos, Cambodia, and the three other colonies that made up what’s now Vietnam.

Jim Thompson was typical of the OSS, which relied heavily on members of such institutions as Yale’s Skull and Bones and Princeton’s various dining clubs. But he was unusual, dangerously so, in that his sympathies were with Pridi (that is, Pridi Banomyong, the leader of Thai’s pro-democracy opposition, who might be called the Franklin Roosevelt of Thailand, in contradistinction to Phibul, its Chiang Kai-shek). Still a patriotic American but one increasingly at odds with the hardline policies that gripped the U.S. after Mao Zedong’s triumph in China, Mr. Thompson wanted to set up his own freelance intelligence network for feeding information back to Washington.

In this, he would be competing with another American spy, Willis Bird, who is said to have been the inspiration for the title character in William Lederer and Eugene Burdick’s novel The Ugly American. Mr. Bird was also going rogue but in support of the pro-fascist forces inside the country, operating a gun-running ring for private profit and advancement of his own beliefs. As for Jim Thompson, Mr. Kurlantzick, who is a thorough, diligent and cautious reporter, will say only that “according to several sources, some of the Southeast Asian fighters depended on Jim Thompson [who,] with his knowledge of arms stocks and his contacts among the Thai leadership, could arrange arms deals for insurgents more easily than any Thai broker.” The author continues: “Because of his old OSS ties, Thompson knew where the United States had left arms caches in Southeast Asia after World War II, and he and other former OSS men, who enjoyed the immunity of working for the new world power, supposedly could get these weapons without having to wade through a thicket of Thai police and other officials asking for bribes.”

In an interview with Mr. Kurlantzick, Rolland Bushner, the U.S. ambassador to Thailand from 1948 to 1952, damned Mr. Thompson as “kind of a romantic. He’d get carried away advocating for these people, like the Vietnamese, like Ho Chi Minh, who was a friend of his, but he didn’t understand the politics of it, that he could get in trouble for what he said.” Trouble could take the form of actions as well as loose talk or overly candid cablegrams. Mr. Thompson, whose marriage back in the States broke up once he failed to leave Asia after the war, was having an affair with the wife of Charles Yost, another senior American diplomat in Thailand (later the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations during the Richard Nixon administration).

The U.S. became increasingly serious about Thailand, which it believed might become the only stable pro-American country in the region as French rule over Indochina weakened. One sign of such growing concern, and growing bad news for Jim Thompson, came when his old boss Wild Bill Donovan succeeded Rolland Bushner as ambassador. Mr. Donovan was free to take up the posting because the OSS had been disbanded not long after the war, supplanted by the new Central Intelligence Agency, which was even more hostile to people such as Jim Thompson, whom it probably considered not even a respectable pro-American entrepreneur but only a freelance of uncertain allegiance. CIA personnel were forbidden to meet or talk with Mr. Thompson, whom the FBI was investigating as well.

Mr. Thompson was still an anti-communist. He was alleged to keep cyanide tablets in his Bangkok bedroom should the communists stage a coup in that city of coups. But he felt that Ho and the others weren’t communists, certainly not first and foremost, but socialists and, most of all, nationalists who wanted their countries back. As time went on, Mr. Thompson also lost much of his support among Thais as the country tumbled through a prolonged series of political and constitutional crises and Pridi, who served as prime minister only briefly, was driven into exile, first in China and eventually in France (where he died in 1983, age 73).

Mr. Kurlantzick is much too sophisticated a writer on politics to fall back on lame conspiracy theories. He is an excellent explainer and interpreter with a special grasp of the history of American foreign policy and the turmoil that Southeast Asia endured in the second half of the 20th Century (including, for example, such unanticipated developments as a three-way civil war in Laos).

What he does conclude is that, given “America’s staunch support for the conservative leadership in Thailand and in Vietnam, Thompson’s views could [have] put him in danger. He openly questioned the Thai leadership and worried that America’s policies were hindering democracy in Southeast Asia and turning the United States into a new type of colonialist.” Less we miss the importance of this sentence, he adds, as his book draws to a close, that Jim Thompson “had increasingly become a nuisance if not an outright danger to the Thais and their American allies….”

Is that all there is to say? Perhaps not. The Jim Thompson case has now engaged the considerable forensic skills of Charles Nicholl, the wonderful British literary historian (one might almost say “literary detective”) whose books include some of the most significant modern biographical studies of Elizabethan figures such as Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Sir Walter Ralegh (scholars no longer spell the name “Raleigh,” feeling that “Ralegh” more accurately reflects its West Country origins). Prof. Nicholl consistently receives high honours for his work, including, most deservedly so, the magnificent biography Leonardo da Vinci: The Flights of Mind (2004). His new book Traces Remain: Essays and Explorations (Penguin Canada, $32) takes a hard look at the site of Jim Thompson’s disappearance and brings us up-to-date in a footnote that, like all his footnotes, is fascinating, if also, in this instance, a trifle long.

Prof. Nicholl describes “a recent flurry in the Malaysian media [that] may be worth mentioning. According to a Cameron Highlands hotel manager, Mr. Lim Wai Ming, a local farmer on his deathbed confessed to his family that ‘he had once knocked down and killed a European man and buried him in an unmarked grave.’ This claim is unsupported — no name for the farmer, no location for the grave — but a former Malaysian police officer, Captain Philip Rivers, backed up the possible connection with the Thompson case. ‘In 1967, it was rumoured that a lorry had struck Thompson on the road, but this was not reported to the police. It was said the driver in his panic placed the body on to the back of his vehicle, drove off and buried the body in the outskirts of a vegetable patch. An alternative story says the culprit was driving a timber lorry and the body was disposed of in a sawmill’ (The Star, Kuala Lumpur, 23 March 2010). A few days later Rivers added a further twist. In about 2000, he claimed, when the old hospital at Tanah Rata was transferred to new premises, a box was found containing human bones which had been ‘brought by an orang asli [forest tribesman] from the jungle’ (Ipoh Echo, 1 April 2012). He speculated that these bones might be Thompson’s and urged local authorities to have them tested, but as far as I know, this has not been done.”

Was there a plot? And if there was, has it thickened or thinned? Who’s to say?

Canadian/Chinese relations: the early days

A book on the order of John D. Meehan’s Chasing the Dragon in Shanghai: Canada’s Early Relations with China, 1858−1952 (UBC Press, $32.95 paper) has been needed for a long time. As the author, a Jesuit scholar in the best tradition, states early on: “Few commentators have seen the need for a comprehensive history of Canada’s Pacific relations. Despite [most historians’] North Atlantic focus, Asian nations, particularly China, had a significant impact on the lives, work, and imagination of many Canadians.” Similarly, Norman Bethune or the thousands of Canadian missionaries were not alone in the impact they themselves had on China. There were Canadian scoundrels, too, such as Two-Gun Cohen, the Nationalist mercenary, and Trebitsch Lincoln, a spy, Anglican curate and later Buddhist monk who supported the warlords on the other side. Mr. Meehan’s deals with all of these but is primarily concerned with the little-known story of Canada’s early attempts at forming a foreign policy towards China and the way such efforts benefitted Canadian business.

The opening date of 1858 in the book’s subtitle is an editorial conceit. That was when Lord Elgin, who had been the governor general of Canada a few years earlier, arrived in Shanghai, which was even then China’s principal city. There he proceeded to wage war until he had captured the imperial seat of Beijing — technically on behalf of the entire British Empire, including ourselves. The book’s closing date, 1952, was when Canada finally closed its diplomatic and consular shops in the new People’s Republic, signalling a period of darkness that lasted two decades. The span of time between the two dates is when Canada, increasingly seen as a distinct strain of British diplomacy and finally, of course, a voice of its own, did much of its best work, however small the scale.

The opening date of 1858 in the book’s subtitle is an editorial conceit. That was when Lord Elgin, who had been the governor general of Canada a few years earlier, arrived in Shanghai, which was even then China’s principal city. There he proceeded to wage war until he had captured the imperial seat of Beijing — technically on behalf of the entire British Empire, including ourselves. The book’s closing date, 1952, was when Canada finally closed its diplomatic and consular shops in the new People’s Republic, signalling a period of darkness that lasted two decades. The span of time between the two dates is when Canada, increasingly seen as a distinct strain of British diplomacy and finally, of course, a voice of its own, did much of its best work, however small the scale.

Japan, not China, was Canada’s largest trading partner in the Pacific. In 1930, Shanghai, population four million, was the sixth-largest city in the world. Of the 60,000 resident foreigners there, a mere 250 were Canadian. Modest though it seemed, the Canadian presence had been built up slowly over the years. When, in 1909, Mackenzie King visited Shanghai for a conference on opium (which Canada had banned the year before) he found copies of the Toronto Globe hanging on rods in the Shanghai Club on the famous Bund, where Canada would locate its trade offices later on. By the time Vincent Massey landed in 1931, heading the Canadian delegation to the Institute for Pacific Relations conference, Canadian businesses were profitably established there. The list of them included not only the Canadian Pacific steamship line but also, for example, a number of Canada’s largest and richest insurance companies such as Sun Life.

Chinese immigration to Canada was another major concern of course. In 1913, 7,444 Chinese immigrated to Canada despite ever-worsening restrictions, such as the notorious “head tax,” brought about by the demands of the western provinces. In 1923, a new act effectively banned Chinese immigration altogether; the legislation wasn’t abolished until 1947. Such racism at home hardly made the job of Canadian diplomats in China, or Canadians there for whatever purpose, any easier. But then the underlying lesson of Mr. Meehan’s narrative is that meaningful interaction with China was always exceptionally difficult, what with China’s failing imperial system succeeded by unstable attempts at republican government, followed by Chiang Kai-shek’s brand of fascism, a Japanese invasion, and a long civil war. During the Second World War, China, again fighting the Japanese, was aligned with the Allied powers. Only then did China and Canada reach their peak of mutual co-operation and respect.

Chinese immigration to Canada was another major concern of course. In 1913, 7,444 Chinese immigrated to Canada despite ever-worsening restrictions, such as the notorious “head tax,” brought about by the demands of the western provinces. In 1923, a new act effectively banned Chinese immigration altogether; the legislation wasn’t abolished until 1947. Such racism at home hardly made the job of Canadian diplomats in China, or Canadians there for whatever purpose, any easier. But then the underlying lesson of Mr. Meehan’s narrative is that meaningful interaction with China was always exceptionally difficult, what with China’s failing imperial system succeeded by unstable attempts at republican government, followed by Chiang Kai-shek’s brand of fascism, a Japanese invasion, and a long civil war. During the Second World War, China, again fighting the Japanese, was aligned with the Allied powers. Only then did China and Canada reach their peak of mutual co-operation and respect.

Two figures in Chasing the Dragon in Shanghai seem to stand out in invisible italics. One is a Methodist cleric, scholar, linguist, lexicographer, Canada-booster — and humanitarian: Rev. Donald McGillivray (1862−1931) of the Christian Literature Society, a familiar figure in the wretched slums of Shanghai. The other is Victor Wentworth Odlum (1880−1971), a far-right Liberal and Vancouver businessman who held the rank of general in both world wars. In 1943, when the invading Japanese had driven Chiang Kai-shek’s forces 1,500 miles up the Yangzi River from Shanghai to Nanjing to Wuhan and finally to remote Chongqing, General Odlum was appointed Canada’s first ambassador extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to China. This required him to arrive in the temporary capital of Chongqing by plane, landing on a sandbar in the river as the city had no airport. When Imperial Japan formally surrendered on the U.S. battleship Missouri in 1945, ending the war, he signed the document on behalf of Canada — but did so on the wrong line. Nevertheless, the treaty was legal and the peace went right ahead.

General Odlum is among the great many diplomats, journalists, spies, scholars and Old China Hands who populate Pursuing China (University of Alberta Press, $34.95 paper) by Brian L. Evans, a pioneer in the growth of Chinese studies in Canadian universities and, later, a junior diplomat himself. His book makes compelling reading but it is an odd affair at times. It begins as an evocative memoir of growing up in rural southern Alberta during the Depression and the war years (and of marrying his high school French teacher). One of his contemporaries in tiny Taber, Alberta, is a Chinese-Canadian named Herbert How whose family’s background first ignites young Brian’s interest in studying Chinese history and culture. He was coming of age, however, at a time when pursuing China was no easy matter.

The communist victory there in 1949 helped to fuel McCarthyism in the U.S., resulting in, for example, the censoring or outright banning of many scholarly works on contemporary China. The American academic community, he writes, more or less “turned to the study of Taiwan and closed itself off from the New China.” The atmosphere “further fuelled my anti-Americanism and turned me toward London.” For Britain, which had recognised the new People’s Republic in January 1950, had a long history of such scholarship. Prof. Evans went to London to study at the esteemed School of Oriental and African Studies (known in jest as the School of Ornamental and Accidental Studies). His doctoral topic concerned “the history of French, British, and Chinese diplomacy regarding China’s southwest frontier in the last half of the nineteenth century.” But the fact that he was appalled by America’s new concern with the “loss” of China to communism doesn’t mean he was sympathetic towards Mao Zedong. China’s Great Leap Forward, intended to redraw and animate the country’s economy, instead led to economic collapse and a famine “in which an estimated twenty million people starved to death […] In three years the Leap was over and China sought wheat from Canada to help feed its people.”

Canada, however, was in no position to be smug. Chinese studies were routinely neglected at universities here. (In 1937, McGill simply gave away its important research collection of 5,000 Chinese books to Princeton in the United States.) The only exception was in Toronto, where interest in the subject was kept alive by a large community of people who had done missionary work in China. Prof. Evans did a great deal to correct this situation when he joined the University of Alberta faculty.

Oddly, it was only in 1964 that he visited China for the first time. Much later, once the Trudeau government recognised the PRC, he signed on as a cultural officer at the Canadian embassy in Beijing. It’s at this point that the tone of the book changes sharply, to use an adverb that is appropriately double-edged. The book’s unfortunate subtitle is “Memoir of a Beaver Liaison Officer”. This refers to an anecdote about how the author was put in charge of caring for a group of beavers sent to China as an official gift, in return, it was hoped, for a panda. The whole last section of the book suddenly becomes rather arch, not to say smart-assed. For example, Prof. Evans is vicious in describing a flying visit to Beijing in 1973 by Jeanne Sauvé, who was then secretary of state for science and technology (and later, of course, governor general). He leaves an impression of her as having been snobbish, uncaring and gauche. But then he himself isn’t always the soul of tact. He remembers that Madame Sauvé brought along her friend Sylvia Ostry, the economist, who said such things as “What do you have to do to get a steak in this goddamned country?”

AND, BRIEFLY…

For reasons having to with both climate change and sovereignty, all of us have become increasingly concerned with Canada’s portion of the Arctic — and with those of the other Arctic nations as well. Yet it’s difficult for us to see the whole situation with the detachment and exactitude that Sara Wheeler, the British travel writer, brings to her new book The Magnetic North: Notes from the Arctic Circle (Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Douglas & McIntyre, $26). As in her previous books, especially Terra Incognita: Travels in Antarctica, she perfectly balances personal experience, description and observation with research, history and science — all in the right proportions. Alas, the photos are reproduced rather poorly.

Xiaobing Li, a Chinese-born American academic, does something quite worthwhile in Voices from the Vietnam War: Stories from American, Asian, and Russian Veterans (University of Kentucky Press, US$25 paper). Our library shelves are heavy with recollections by U.S. veterans of the Vietnam War — and with more examples by Vietnamese veterans than you might expect to have been translated into English or French. Prof. Li looks farther afield, setting down the stories of, for example, Russian missile experts and Chinese railway-builders seconded to North Vietnam, or a South Korean battlefield surgeon working with the Americans. Their perspectives help to round out the picture of that war. The same author previously published A History of the Modern Chinese Army (in which he once served). Now the subject is updated a bit in the revised edition of A Military History of China (also University of Kentucky Press, US$25 paper). The editors, David A. Graff and Robin Higham, assemble a wide range of academics and independent scholars from the U.S., Canada and, of course, China. This type of symposium-between-covers is an ever-growing part of academic publishing. Another fresh example is Canada’s National Security in the Post−9/11 World: Strategy, Interests, and Threats (University of Toronto Press, $27.95 paper). The editor, Donald S. McDonough, gathers a sampling of academic and military thought from Americans and Britons as well as Canadians. Among the latter are Senator Hugh Segal and J.L. Granatstein, the historian. (See an excerpt from one of the essays, “Shift to the Pacific” by Thomas Adams, beginning on page 38 of this issue.)

The idea of travel literature organized around some framing device (or editorial gimmick) never seems to grow stale. Authors of such books often set out to follow in the footsteps of — well, somebody, just about anyone, who went before. In Landfalls: On the Edge of Islam from Zanzibar to Alhambra (John Murray, $16.99 paper), Tim Mackintosh-Smith shadows Ibn Battutah, a Medieval traveller from Tangier. Much more imaginative is Rachel Polonsky’s book Molotov’s Magic Lantern: Travels in Russian History (Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Douglas & McIntyre, $31). The author is a British writer who moves to Moscow and finds the residence once occupied by Vyacheslav Molotov (1890−1986), the old Stalinist associated with the notorious Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pack of 1939. Inside she discovers his personal library, still intact (as well as his magic lantern). Ms Polonsky then traipses round the new Russia, visiting the places that Molotov knew from his personal reading: sites associated with Pushkin, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, and others. Sounds a bit contrived but it all works beautifully.

George Fetherling’s book The Writing Life: Journals 1975−2005, edited by Brian Busby, will be published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in the spring.