Thomas Dormandy, a retired British pathologist who knows whereof he speaks, has a great deal to tell us about opium as well as morphine and heroin, the two even more powerful painkilling drugs derived from it. His exhaustive, but not exhausting, new book, Opium: Reality’s Dark Dream (Yale University Press, US$40), is a splendidly informative and enjoyably written social history of the subject.

Naturally it is full of information on the use of opiates in medicine and the role they play in crime, but it also deals quite substantively with opiates in art, literature, pop culture, myth, politics, business and war. For example, Dr. Dormandy offers frightening statistics about addiction levels among U.S. military personnel during the Vietnam War, when heroin was North Vietnam’s most effective weapon. I was halfway through this intriguing book, having just passed a photo of U.S. soldiers spraying insecticide on Afghan poppy fields in 2008 (“Eradicating the poppy was later recognized as incompatible with the winning of hearts and minds”) when I paused to pick up the morning newspaper and spotted a pertinent story.

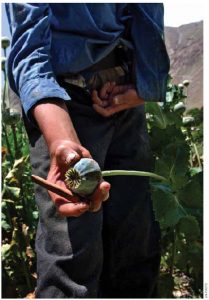

By a large margin, Afghanistan is the world’s biggest producer of opium (a title long held by India during the days of the Raj). The paper reported that the white poppy harvest in Afghanistan — the red variety, which grows wild, has no narcotic effect — peaked in 2007 and in the past several years has been declining, despite its importance as the primary cash crop of the country’s poor and one of the main sources of revenue for insurgent fighters. Now, the news story reported, a new plant disease is blighting the crop. This led to “heroin droughts” in some places, apparently causing many users to turn to drugs made, not from the poppy, but rather, like cocaine, from the coca plant.

The report put particular emphasis on desomorphine (the street name is “krokodil”): “a crude codeine-based drug that users inject.” What all the above says to me is that opium, unlike methamphetamine and the other man-made drugs that are quickly eroding opium’s market share internationally, has often been bound up with classical economics and with social and foreign policy and hence, sometimes, with diplomacy as well.

The most famous physician of the 19th Century, Sir William Osler of McGill University and later Oxford, called opium “God’s own medicine,” for it certainly eliminated pain and did so quickly. In Switzerland, there is archeological evidence of opium use during the Stone Age, long before it spread to the ancient Assyrians, the Sumerians (who called it Hul Gil or “plant of joy”), the Persians, the Egyptians, and so on, down into Greek and Roman times. In those last two civilizations, it took the form of a hard cake mostly for consumption at home. Arab traders introduced what they called affyon (also romanized as af-yum, ufian or asiun) to India and China.

The stuff had uses even when not smoked, taken as a tincture or (later on) mixed with alcohol to make laudanum. Early Arabic sources, Dr. Dormandy tells us, indicate that it “could also be used in diplomatic bargaining.” Certainly it could be taxed, becoming thereby a multi-purpose treatment for political and social woes as well as relief of human suffering. In time, its use spread almost everywhere, especially to Europe, Britain and the young American republic. Franklin Roosevelt owed his family fortune to his ancestors, the Delano clan, who prospered in the opium business. But it was only when the two Asian giants, India and China, were forced into two-way trade on an unheard-of scale that opium became a major international epidemic.

Chinese physicians had been prescribing medicinal opium for ages when, in the late 17th Century, Dutch and Portuguese sailors introduced the population to tobacco — and to the maritime practice of adding a touch of opium to the bowl of the pipe. Tobacco addiction became so widespread that the emperor banned it — but not opium, which became the new addiction, at least for the wealthy. Then, in 1793, the East India Company, the London-based joint-stock company that had taken over much of the Indian subcontinent — operating its own army and navy, even issuing its own coinage — sent an emissary to the Manchu court in Beijing, which had banned foreign opium 14 years earlier. A long and maddeningly complex series of diplomatic initiatives brought the British no satisfaction, though opium still got through.

In 1839, the emperor began publicly burning stocks of imported opium. The following year, two British frigates arrived and destroyed the Chinese fleet, igniting what has gone down in infamy as the First Opium War (to distinguish it from the Second Opium War of 1853, another one-sided victory for the British). Foreign traders had long been limited to one small section of Canton (Guangzhou). The British and others demanded and got free “treaty ports” and fat reparations. Opium from British India now floated into China almost to the point of drowning it.

China’s opium problem lasted into the first half of the 20th Century. Chiang Kai-shek’s dictatorship was backed up by opium taxes as well as American aid money. Whatever else they did, the communists under Mao Zedong banned opium effectively, italicizing their point by executing tens of thousands of addicts and suppliers. The sudden availability, in the 19th Century, of syringes for subcutaneous injection had given medical people and self-medicating individuals a new and faster way to deliver the drug to the brain. The device was especially useful in wartime. Florence Nightingale not only used it to treat her wounded charges but regularly injected herself as well. By then, and for several generations afterwards, opium was an element in all manner of quack remedies and patent medicines. One especially popular American elixir named Mother’s Friend was given to infants who cried more than their parents could tolerate. Some of the babies died of an overdose.

Opium was legal in North America until the early 20th Century, by which time more dangerous souped-up opium products had long been available. As long ago as 1827, Merck, now one of the largest drug companies in the world, began marketing morphine. Although many unsupervised individuals would become addicted to it as time wore on, the drug was under the control of medical professionals to an extent that plain old opium never was. But this “medicalisation,” to use Dr. Dormandy’s term, was double-edged. While many physicians expressed concern about use of the drug for purposes other than surgery, many others were themselves recreational users. Dr. Dormandy cites an American physician who proclaimed in 1885 that one-third of all medical doctors in New York City were addicted to morphine.

This was not the case with heroin, which was made available in 1898 by the German firm that is now the worldwide purveyor of Aspirin and such, Bayer AG (pronounced BY-er in German). Heroin had five times the power of morphine. The medical community respected its potential to harm and kill, even though, paradoxically, heroin in its early days was not thought habit-forming and indeed was considered a cure for morphine addiction. The 1930s American gangster, Lucky Luciano, was, so to speak, the marketing genius behind the spread of heroin to his nation’s back alleys and other dark urban spaces.

Opium, which requires enormous labour, skill and patience to cultivate and harvest, has been fighting a losing battle for decades now with drugs that any smart chemistry grad student might concoct: ecstasy, crystal meth, and so on. Yet, as Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy shows us in his book, Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy (Harvard University Press, US$27.95), opium and its two main derivatives still command attention and warrant great concern, partly because they are very much victors and victims in geopolitics and the policies of various governments.

First, there was the area of northern-most Thailand and Myanmar that became known as the Golden Triangle, because opium middlemen would trade their commodity to other middlemen in exchange for ingots of 99-percent pure gold. (So claimed Bertil Lintner from Sweden, one of the world’s most skilled reporters, who for years somehow managed to file from inside Myanmar when being a journalist there was, to say the least, a felony.) The Triangle lost much of its importance by the late 1990s, but continues to provoke thoughtful books such as a recent work by Thein Swe and Paul Chambers titled Cashing in across the Golden Triangle: Thailand’s Northern Border Trade with China, Laos, and Myanmar (University of Washington Press, US$20 paper). Such works have a slightly historical ring to them now that attention has turned instead to the Golden Crescent in Central Asia.

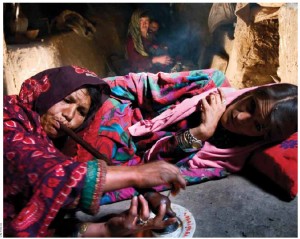

The Crescent’s rise was slow at first, owing to politics and war. For example, when the last shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, banned opium in 1955, he opened the door for increased production in Pakistan and Afghanistan, which, by the time of his death in 1980, were flooding the market — Afghanistan especially. This has been the pattern: as one supplier nation has been forced to cut back, another rises to prominence.

The Crescent’s rise was slow at first, owing to politics and war. For example, when the last shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, banned opium in 1955, he opened the door for increased production in Pakistan and Afghanistan, which, by the time of his death in 1980, were flooding the market — Afghanistan especially. This has been the pattern: as one supplier nation has been forced to cut back, another rises to prominence.

On the one hand, opium exists, or doesn’t, at the whim of various governments. One suspects that the U.S. will force the newly liberalized Myanmar to suppress opium — as a trade-off, one might say, for the office towers, luxury hotels and Starbucks that will begin popping up there before too long. But drug suppliers worldwide are skilled manipulators, as sensitive to economic change as any foreign-exchange arbitrageur. Mr. Chouvy, who is a fellow of the Centre national de la recherche scientifique of Paris, points out that a kilogram of Afghan opium sold for between US$95 and US$120 once the Taliban drove down the market price, but rose to US$500 after American troops arrived.

Mr. Chouvy has written a thorough book. If not nearly so readable as Dr. Dormandy’s, it has a section of useful maps and a fine bibliography — from which we learn that the fellow author Mr. Chouvy quotes most often is A.W. McCoy, who wrote The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972, later revised), a work that stands alongside Mr. Lintner’s own classic in the field, Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948 (1994).

Mr. Chouvy has written a thorough book. If not nearly so readable as Dr. Dormandy’s, it has a section of useful maps and a fine bibliography — from which we learn that the fellow author Mr. Chouvy quotes most often is A.W. McCoy, who wrote The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia (1972, later revised), a work that stands alongside Mr. Lintner’s own classic in the field, Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948 (1994).

Are there still opium addicts here in the West when chemical opioids and other not entirely organic drugs have sopped up the market? Unfortunately, yes, on the basis of Steven Martin’s dramatic-sounding book, Opium Fiend: A 21st Century Slave to a 19th Century Addiction (Random House of Canada, $31 cloth). Mr. Martin was an expat American and naval veteran when he worked in Thailand as a travel writer and freelance reporter. He became fascinated with opium pipes and the other paraphernalia used in opium smoking in earlier times. He built an important collection of these artifacts, which he then drew on for his first book, The Art of Opium Antiques. Unfortunately, he was also using them for the purpose for which they were intended. His new book describes how he underwent a successful withdrawal. It is every bit as horrifying as Thomas De Quincey’s famous Confessions of an English Opium-Eater but, needless to say, far more readable. Near the beginning he writes, “I began to dwell on morbid visions of my corpse being discovered, the centerpiece of a room that looked as though it had been ransacked by a madman.” You get the idea.

AND BRIEFLY…

More than once I’ve written in this space about Robert D. Kaplan, the virtually unique combination of foreign policy analyst, defence and security consultant, travel writer extraordinaire and all-round public intellectual. His new book The Revenge of Geography (Random House of Canada, $34) puts the emphasis on geo in the word geopolitics. It’s astonishingly wide-ranging if also a trifle familiar, as it reprints much material from four of Mr. Kaplan’s previous books, albeit four of his lesser known ones, not Balkan Ghosts: A Journey through History or Ends of the Earth: A Journey at the Dawn of 21st Century.

Timothy Wilford’s book, Canada’s Road to the Pacific War (UBC Press, $37.95 paper), is the latest work of scholarship to further the growing interest in Canada’s Asia Pacific role in the mid-20th Century. “Intelligence, Strategy, and the Far East Crisis” is its subtitle.

One of the more topical new books of interest is Thomas Graham Jr.’s Unending Crisis: National Security Policy after 9/11, focusing on North Korea, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and other hot spots. Another is Contagion: Health, Fear, Sovereignty, in which Bruce Magnusson and Zahi Zalloura assemble recent thinking on biological warfare and naturally occurring epidemics. Both books are University of Washington Press paperbacks (US$24.95).

As for humanitarian disasters, they are the subject of Africa’s Deadliest Conflict (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, $38.95 paper), in which Walter C. Soderlund and three others examine the sorry story of the media’s coverage of — and the United Nations’ role in — the war in the Congo. These events figure prominently in Ian McKay and Jamie Swift’s Warrior Nation: Rebranding Canada in an Age of Anxiety (Between the Lines, $26.95 paper), a study of rising militarism.

George Fetherling’s book The Writing Life: Journals 1975—2005 will be published in April by McGill-Queen’s University Press.