Canada and Mexico, living alongside and often in the shadow of the colossus of the 20th Century, have long seen their place in the world as deeply coloured by the reality that they are of the Americas, but not Americans. The two countries have benefited from their proximity to the largest economy on Earth and shelter under its security shield, but have been equally determined to maintain their separate identities and values. As a result, they have honed the skills of idea shapers, coalition brokers and bridge builders. Unlike Americans, they have had to learn how to speak softly, but convincingly, in the full knowledge that they do not carry a big stick.

Canada and Mexico, living alongside and often in the shadow of the colossus of the 20th Century, have long seen their place in the world as deeply coloured by the reality that they are of the Americas, but not Americans. The two countries have benefited from their proximity to the largest economy on Earth and shelter under its security shield, but have been equally determined to maintain their separate identities and values. As a result, they have honed the skills of idea shapers, coalition brokers and bridge builders. Unlike Americans, they have had to learn how to speak softly, but convincingly, in the full knowledge that they do not carry a big stick.

What surprises is that Canada and Mexico have accomplished so little together, given their similar interests in learning how to live in harmony with, but remaining distinct from, the United States, and their analogous experiences as middle-level powers. While they can celebrate nearly 70 years of diplomatic relations, those years have not been distinguished by many major achievements. Relations have been cordial and harmonious, but they cannot be said to have been productive. The potential for more has always been there, but until recently, that potential never seemed capable of being translated into concrete results.

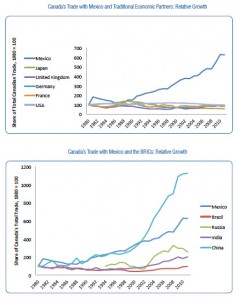

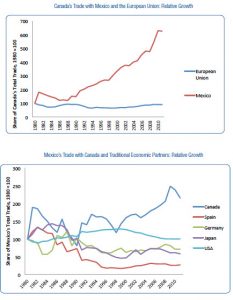

The 1994 NAFTA provided the opportunity to redefine the bilateral relationship. While Canada may have joined the NAFTA talks to preserve the gains from the 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, this “reluctant” decision proved to be remarkably rewarding (Bugailiskis and Dosma, 2012). Canada not only succeeded in protecting its primary market with its most important trading partner — the United States — but it also found a new partner in Mexico. Since NAFTA, Canada’s trade with Mexico has grown nearly six-fold. Today, Mexico is Canada’s third-largest trading partner, with two-way trade reaching $34.4 billion in 2011. Canada’s exports to Mexico reflect the breadth of the Canadian economy and run the gamut — from pulses to airplanes.

The 1994 NAFTA provided the opportunity to redefine the bilateral relationship. While Canada may have joined the NAFTA talks to preserve the gains from the 1988 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, this “reluctant” decision proved to be remarkably rewarding (Bugailiskis and Dosma, 2012). Canada not only succeeded in protecting its primary market with its most important trading partner — the United States — but it also found a new partner in Mexico. Since NAFTA, Canada’s trade with Mexico has grown nearly six-fold. Today, Mexico is Canada’s third-largest trading partner, with two-way trade reaching $34.4 billion in 2011. Canada’s exports to Mexico reflect the breadth of the Canadian economy and run the gamut — from pulses to airplanes.

Growth in bilateral trade started slowly, but has picked up speed over the past decade as Mexico put the peso crisis of the mid-1990s behind it and learned to take advantage of NAFTA’s opportunities. Increasingly, Mexico has become an integral part of North American-based supply chains, and much of its trade with its NAFTA partners is inter-corporate. As the Financial Times points out: Mexico is now vying with China as the manufacturing hub of choice for U.S., [Canadian], and other multinational companies — it is as economically integrated with the U.S. [and Canada] as any two members of the euro-zone are to each other. Much of this is driven by the rise in the cost of oil, which makes transport costs increasingly pricey for U.S. companies to make goods for domestic consumption as far away as East Asia. And most of the rest is driven by Chinese wage inflation. In 2000, the average Chinese worker was paid 35 cents an hour versus US$1.72 in Mexico, according to HSBC. Now the Mexican gets paid US$2.11 an hour and the Chinese US$1.63. Pretty soon Mexico will have the lower labour costs. (Luce, 2012.)

The growth in the bilateral economic relationship has not been limited to trade. Canadian investments in Mexico have more than doubled since the late 1980s, as Canada has become one of Mexico’s largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI). More than 2,600 Canadian companies have offices and operations in Mexico, including major firms such as Bombardier, Goldcorp and Linamar. Companies in industries ranging from finance to pharmaceuticals, such as Scotiabank and Apotex, have used their Mexican operations as launch pads to reach other markets in Central and South America. Mexican firms such as Cemex, Grupo Bimbo and Univision have begun to make significant inroads into the United States, but to date have not shown much interest in expanding to Canada.

The growth in the bilateral economic relationship has not been limited to trade. Canadian investments in Mexico have more than doubled since the late 1980s, as Canada has become one of Mexico’s largest sources of foreign direct investment (FDI). More than 2,600 Canadian companies have offices and operations in Mexico, including major firms such as Bombardier, Goldcorp and Linamar. Companies in industries ranging from finance to pharmaceuticals, such as Scotiabank and Apotex, have used their Mexican operations as launch pads to reach other markets in Central and South America. Mexican firms such as Cemex, Grupo Bimbo and Univision have begun to make significant inroads into the United States, but to date have not shown much interest in expanding to Canada.

After the United States, Mexico is now the largest foreign destination for Canadians. The majority of these are short-term visitors, but there are also a growing number of business, student and other long-term residents living in Mexico. In the other direction, Mexico is the second-largest source of temporary foreign workers for Canada, boosting the productivity of Canada’s agricultural sector through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program. As Canada’s labour force continues to age, Mexico offers a rich source of younger workers upon which to draw. The earlier flood of illegal migration across the Mexico-U.S. border has slowed to a trickle, while many older Mexicans are now returning home to pursue new opportunities closer to their families. Agreed labour mobility programs have become much more attractive. Mexicans are also studying abroad in increasingly large numbers, yet Canada attracts only five percent of this market.

Despite these growing levels of economic interaction, most Canadians and Mexicans still hold largely stereotypical images of each other. Many Canadians see Mexico as sun, sand and margaritas, while others focus on criminality, corruption and drugs (Jiménez, 2012). Mexicans, meanwhile, when polled, often reply that Canada is their favourite foreign country, but as the editor of the Mexican daily Excélsior puts it, “we know nothing about Canada and that may be the reason we like it” (Carreño Figueras, 2012). In short, the two countries have much to learn about one another, and there is a tremendous opportunity to increase that knowledge by, for example, increasing exchanges between Mexicans and Canadians through labour and student mobility agreements and initiatives.

The election of Mexico’s new president presents an opportunity to recalibrate bilateral relations and look for ways to upgrade and change those relations to a strategic partnership. The ongoing shift in global economic power from Western Europe and North America to the emerging economies of Asia and Latin America and their burgeoning middle classes provides a compelling reason to strengthen Canada’s engagement with Mexico. Everyone, including Canada, may be preoccupied with the fast-growing economies of China, India and Brazil, but the success of these economies remains a mixed bag for Canada. On one hand, they offer new investment and trade opportunities. On the other, multinational firms from these economies increasingly do not “play by conventional, market-based rules,” and their governments are unafraid to guide these firms to act in the state’s interest. (Burney et al., 2012).

As global competition becomes more intense, Canada and Mexico could each benefit from taking a broader view of North American relations and from thinking about how to strengthen regional economies. The three North American economies enjoy enormous complementary potential. Canada and the United States are rich in skilled labour and value-added industries, Mexico boasts a young and growing workforce, and all three are rich in natural resources. An enhanced economic partnership among Canada, Mexico and the United States will make North America as productive and competitive as any other major economic area. To make such an enhanced partnership a reality, Canada and Mexico must first strengthen their bilateral bonds.

To that end, the two countries should realize that despite growth in bilateral trade and investment, they may be leaving economic opportunities lying on the table. Today, Canada’s economy is larger than Mexico’s, but within a few decades the relative position of the two countries will switch. PricewaterhouseCoopers projects that, on a purchasing power parity basis, Mexico’s GDP will be US$6.6 trillion by 2050 — the seventh-largest economy in the world — twice Canada’s projected GDP of $3.3 trillion (Elliot, 2011). Additionally, by 2050, one in six Americans will be of Mexican ancestry (Zubieta, 2012). In short, the Mexican economy and the Mexican diaspora will provide new and compelling opportunities for trade and investment far too large for Canadians to ignore.

The Canada-Mexico relationship may also become progressively more important as a result of demographic factors. In many of Canada’s traditional developed-world trading partners, population and economic growth have slowed; Mexico, on the other hand, enjoys the economic dividends that come from having a relatively young population and a growing middle class. Not surprisingly, while trade with Mexico has grown six-fold since 1980, Canada’s trade with its traditional economic partners such as Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and France has remained flat or declined. Even Canada’s trade with the United States has declined as a proportion of total trade since the early 2000s. v

The two economies complement one another: Canada’s older, relatively skilled workforce can provide research and design services, while Mexico’s abundance of lower-skilled younger workers are ideal for manufacturing and resource extraction. Both countries also have large reserves of natural gas, oil and mineral resources that are being developed to their maximum potential. Additionally, Mexico is not just a lucrative market for Canadian businesses: it also offers a gateway to the U.S. Spanish-speaking market and the rest of Spanish-speaking Latin America.

Canada may also become an increasingly important source of capital for Mexico. The United States has traditionally been Mexico’s principal investment partner, supplying more than 70 percent of foreign direct investment in Mexico in the early 2000s. The global financial crisis highlighted Mexico’s need to diversify its FDI sources: as the United States fell into recession in 2009, Mexico’s FDI inflows collapsed to 60 percent of their 2008 levels (Laudicina, Gott and Pohl, 2010). Canadian FDI in Mexico has doubled since NAFTA, and Canada is now Mexico’s fourth-largest source of FDI. While this growth is important for boosting Mexican productivity and lessening its reliance on American capital, it is a modest increase when compared with trade growth. It also represents less than one percent of Canada’s overseas FDI stocks, suggesting that there may be mutually profitable investment opportunities waiting to be pursued.

In the immediate future, there are useful opportunities for Canada and Mexico to collaborate on regional and international issues. Both boast large hydrocarbon industries and both have relatively carbon-intensive economies. It may be in both states’ interests, for example, to co-ordinate their planning for a carbon-pricing scheme that will eventually involve the United States. Given the gross inequality in power between the United States and Canada or Mexico alone, Mexican-Canadian co-ordination on some continental issues could help even the playing field. This applies, for example, to pursuing greater alignment in regulatory regimes.

At the same time, it is important not to lose sight of the significant transnational crime challenges confronting the government of President Peña Nieto. Mexico has suffered 55,000 drug-related deaths since former president Felipe Calderon launched the “war on drugs” in 2006, although Mexico’s drug-related murder rate is still lower than that of Colombia, Venezuela, Honduras, Guatemala and other parts of Central America and the Caribbean. The cartels have responded to the war on drugs by spreading their business throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. Mexico’s drug violence may be largely confined to the border areas with the United States, but the continued violence and corruption that accompanies the drug trade corrodes public confidence in Mexico’s security services and its potential as a strategic partner. Canada already assists Mexican efforts to train and upgrade the skills of Mexico’s judiciary and police, but increasing assistance would be a natural complement to Canada’s own anti-drug efforts. In the long run, strengthening the relationship will require Canada to continue to support Mexico’s efforts at governance and security sector reform.

Ultimately, turning the bilateral relationship into a strategic partnership will mean realizing that what is good for Mexico can also be good for Canada. Further strengthening Mexico’s economy will not only help the 52 million Mexicans who live in poverty, but will also enhance Canada’s ability to service Mexico’s growing middle class. A concerted effort by both parties to build and improve upon the existing relationship could multiply existing benefits several-fold.

From a Canadian perspective, several policy initiatives should contribute to strengthening the bilateral relationship. To that end, the recommendations take two views of what needs to be done: In the short-run, Canada and Mexico should strive, wherever possible, to reduce barriers to the movement of goods and people between the two countries. Longer-term, Canada should support Mexican efforts to further reform the Mexican economy and to deal with organized crime. A stronger, wealthier, less-violent Mexico will, ultimately, make for a stronger, more prosperous Canada-Mexico relationship.

This report, a joint effort by The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, is published with permission. It is available online http://www.cigionline.org/publications/2012/11/forging-new-strategic-partnership-between-canada-and-mexico.