To many, Mexico is merely a holiday destination, a place of sun, sand and cerveza, its people represented by the smiling members of the service industry at resorts, shops and tourist traps. Outside the perfectly landscaped resorts are intriguing Mayan and Aztec ruins, as well as drug cartels and the rampant corruption within the police and government. Officially Estados Unidos Mexicanos (United Mexican States), Mexico is a complex country that feels the weight of its authoritarian history. It has been shaped by revolution, violence and assassinations — so says author Jaime Suchlicki, From Montezuma to NAFTA and Beyond — but its history also includes high levels of culture, learning and innovations of tremendous magnitude.

Mexico’s earliest inhabitants can be traced back to at least 11,000 BC.

Although the best-known early civilizations were the Maya of the Yucatan Peninsula and southern Mexico, and the Aztecs of central Mexico, there were many significant indigenous civilizations with different social and economic systems. Among them were the Chichimecs, Toltecs, Zapotecs, Tlaxcalans and Tarascans. Many early groups developed high civilizations with elaborate urban centres that served religious, political and commercial purposes, including the Mayan city Chichén Itzá and the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, both now must-see tourist destinations.

Mexico’s “Mother Culture”

Anthropologists consider the Olmec people as Mexico’s “mother culture,” the political, social, economic and religious models of subsequent civilizations. Their culture flourished between 1200 and 400 BC near southern Veracruz and western Tabasco. Although trade and conquest were significant, religion spread Olmec culture. Their two cults, the jaguar and the serpent, influenced succeeding religious thought.

The Maya

Mayan civilization arose circa 2600 BC. (Tourists know the Yucatan Peninsula as the Mexican Riviera.)

The Maya gained prominence by AD 250; their territory covered what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and parts of Honduras and El Salvador. The Maya developed astronomy, hieroglyphic writing and systems of calendars, including the Long Count (52-year) calendar. They are also noted for elaborate architecture that included pyramids, palaces and observatories. Farming required clearing large sections of rainforest and constructing underground reservoirs for rainwater. The Maya cleared routes through jungles and the swamps of the coastal wetlands to establish extensive trade networks for agricultural products, including cacao, cotton, salt and honey and handicrafts. In the interior Yucatan, where the landscape changes to arid scrub, they found henequen, a native agave plant they used to make ropes, nets, fabric, hammocks and other items of everyday use and trade.

Mayan civilization mysteriously declined around 900 when the southern Maya abandoned their cities. By 1200, the northern Maya had been assimilated into Toltec society, which derived from the Chichimecs. The Mayan dynasty ended, although some peripheral centres continued until the Spanish Conquest.

The Aztecs

“They came in battle array, as conquerors, and the dust rose in whirlwinds on the roads, their spears glinted in the sun, and their pennons fluttered like bats. They made a loud clamor as they marched, for their coats of mail and their weapons clashed and rattled … they terrified everyone who saw them.” This Aztec account, which was translated by Miguel León-Portilla and appears in A Brief History of Mexico by Lynn V. Foster, clearly describes the strength and intensity of the Aztecs. However their history before the 14th Century is unclear. They probably migrated from the north into central Mexico before 1200 and were, for a time, dominated by other peoples, including the Toltecs. Their migration fulfilled a tribal prophecy when they established a city where an eagle with a snake in its beak rested on a cactus. This became Mexico’s national symbol and today adorns the flag and official seal.

Tenochtitlan, which was built about 1325 at what is now Mexico City, was the centre of an empire that controlled most of the central region through a system that extracted tributes — taxes — and political allegiance from conquered groups. Built on an island accessed by causeways, the city featured avenues, temples and religious monuments symbolizing Aztec power. Larger than any European city, it was a wondrous sight to the Spanish when they arrived to destroy it.

The Aztec empire was shaped by the reign of Montezuma I, who waged war for two decades to conquer the Valley of Mexico and beyond to the rich fields of the Gulf coast. The Maya and Toltecs influenced the Aztec calendar, mathematics, writing, art and architecture. The Aztecs’ most significant innovation was their irrigated agriculture, which supported Tenochtitlan’s population.

Religion was significant in Aztec society, which placed priests among the top social classes. They saw the sun as the primary source of life and worshipped animistic spirits symbolizing natural forces. The rhythms of life and death encouraged Aztec acceptance of the Toltec belief that the gods required human sacrifice, a practice much exaggerated by the conquistadores. Each Aztec city had a pyramid topped with a temple where priests honoured Huitzilopochtli, the god of sun and war.

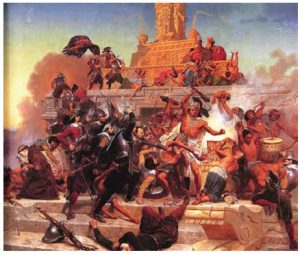

The Spanish Conquest

Hernán Cortés reached Cozumel in 1519, lured by the vast wealth reported by Hernández de Córdoba, who reached the Yucatan in 1517. Spain’s conquest of Mexico marks the rise of the modern nation of combined indigenous and European cultures.

Montezuma II ruled the Aztec empire when Cortés arrived in his ships with a few hundred soldiers and their horses, war dogs, armour, gunpowder and firearms, all of which were unknown and therefore intimidating. Uncertain, Montezuma hesitated to face the enemy and sent shamans and magicians to cast spells. When they failed, and receiving news that Cortés wanted to meet the great ruler, Montezuma stalled by sending gifts of gold and jewels, whetting the Spanish appetite further. Cortés and his army journeyed to Tenochtitlan. They were driven out on the Noche Triste (sad night), June 30, 1520, when the Aztecs overwhelmed the Spanish as Cortés led their retreat. Among the casualties was Montezuma. Cortés rebuilt his army and returned, taking the city on Aug. 13.

Between 1519 and 1521, aided by large armies made up of the Aztecs’ enemies, Cortés and his conquistadores conquered the Aztecs. Over the next 10 years, they subjugated most of the other indigenous people and erected the capital of New Spain on the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

Cortés’ activity was largely illegal; he was authorized to trade, not colonize, but he assumed that Spain’s king, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, would not object to a wealthy conquered kingdom. He assumed correctly and ultimately became one of the richest men in Spain. Mexico remained a Spanish colony until 1821; the Spanish empire profoundly marked every aspect of Mexican society.

Mexican independence

On Sept. 16, 1810, the priest Miguel

Hidalgo called for independence, exhorting Mexicans to rise up against the hated Spanish, and led a poorly organized rebellion on what is now marked as Mexican Independence Day. Hidalgo was hanged and another priest, José Morelos, took up the cause with a more methodical movement. He advocated equal rights and the end of the caste system, laying the foundation for a unified Mexican nation. Spain executed him in 1815.

The Spanish defeated the revolutionaries and independence was eventually won by conservative landowners. Mexico suffered a series of nearly catastrophic political and military defeats. Between 1836 and 1854, the United States acquired nearly half of Mexico’s territory through the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War. Achieving independence left Mexico without a political centre and with a damaged economy and social system that would hold it back for decades.

Benito Juárez

In 1857, a civil war pitted liberals, under reformist Benito Juárez in Veracruz, against conservatives led by Félix Zuloaga in Mexico City. In 1861, Juárez’ forces captured Mexico City, but the conflict coincided with growing foreign debt. Mexico was insolvent and Juárez had to suspend payments on its debts.

Spain, France and Great Britain occupied Veracruz to recover money owed to them. Napoleon III, wanting to revive France’s global ambitions, set out to capture Mexico City; Spain and Britain withdrew when his plans became clear. Mexican armies won a major battle against the French on May 5, 1862, despite being severely outgunned; that victory is celebrated as Cinco de Mayo. France overthrew the Mexican government and installed Maximilian, Archduke of Austria, as emperor of Mexico in 1864.

The American government disapproved, but because of its own Civil War, was unable to enforce the Monroe Doctrine prohibiting European involvement in the Americas. Additionally, president Abraham Lincoln was wary of antagonizing Napoleon, fearing he would support the Confederacy. The American Civil War ended in 1865 as Juárez began to make headway against Maximilian. By then, the Mexican intervention had become unpopular in France and a burden on the French treasury. Napoleon withdrew and Maximilian was unable to retain power. His execution on June 19, 1867, marked the end of Europe’s direct intervention in Mexico.

Porfirio Díaz, who had fought for the liberal side, became president in 1876 and ruled as an absolute dictator until 1911. He encouraged foreign investment, increased the GDP and implemented a program of industrial modernization. He also appropriated public money and gave land to friends and speculators until property had been expropriated from virtually all rural families. The economy boomed, but the lower classes laboured in abject conditions.

The Mexican Revolution

In 1910, Díaz announced a fair and free election, certain he would win. Reformist Francisco Madero opposed him. When it became apparent Madero would win, Díaz imprisoned him on false charges of insurrection. Madero escaped to Texas, declared himself victorious, and urged Mexicans to revolt. Central to the revolution’s demands was land for the peasantry.

Armed revolutionary groups were led in the north by bandits-cum-revolutionaries Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco and in the south by Emiliano Zapata. Villa and Orozco’s armies attacked federal garrisons, attracting recruits and building their arsenals. Villa believed in a reformed and less corrupt Mexico; Orozco was an opportunist siding with the force he thought would win. Zapata and his followers, the Zapatistas, attacked haciendas and returned land to the peasants. Early in 1911, Madero joined the three generals as they neared the capital. By May, Díaz realized he was beaten and went into exile.

Madero’s presidency was short-lived; he was idealistic, but inept, and had no real plan. He betrayed his supporters, who took up arms against him. By mid-1912, only Villa supported him. His biggest opponent was Gen. Victoriano Huerta, a ruthless leftover of the Díaz regime with presidential ambitions. He attacked Madero during a standoff with Díaz loyalists, executed him and declared himself president.

Huerta was opposed by Venustiano Carranza and Alvaro Obregón, who were united with Zapata and Villa. The only thing the “Big Four” agreed on was driving out Huerta. Before long, they were fighting each other. Huerta had Orozco’s support, but it was insufficient. After Villa crushed them at the Battle of Zacatecas, Huerta and Orozco fled to the United States. The following years were chaotic. Zapata was killed, but his ideal of agrarian reform became the foundation of the revolution. Carranza overthrew Huerta and sent Obregón to defeat Villa, who retreated to Chihuahua and raided border towns in New Mexico, killing several Americans. Gen. John Pershing was sent unsuccessfully to capture him. Villa was assassinated in 1924.

Carranza became president in 1917. His major accomplishment was drafting a constitution that remains the basis of today’s Mexican constitution. It sought to destroy feudalism and to guarantee national ownership of mineral rights, social rights and distribution of land to the peasantry. Carranza was assassinated in 1920 by supporters of Obregón, who replaced him.

Obregón was re-elected in 1928, but was assassinated, the last of the Big Four. Gen. Plutarco Calles filled the office of interim president with three successive puppet presidents and founded the National Revolutionary Party, which became the Mexican Revolutionary Party and then the Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or PRI), which dominated Mexican politics for seven decades.

Because Obregón served a full term as president, many historians fix the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, but the country suffered terrible violence until Lázaro Cárdenas took office in 1934.

Post-revolutionary reforms and the contemporary state

Cardenas expelled Calles, advanced land redistribution, built schools, supported labour unions and nationalized the oil industry. Four decades of industrial growth followed, but in 1982, despite Mexico’s oil wealth, the economy collapsed under a mountain of debt.

On Jan. 1, 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. In Canada and the United States, critics and supporters predicted the pact’s success or failure. In Mexico, the agreement was upstaged by an uprising in Chiapas by the Zapatista National Army (EZLN) protesting the government’s treatment of its indigenous population. The uprising spread across Mexico, including the capital, challenged national stability into the late 1990s and killed more than 300 people.

In March 1994, PRI nominee Luis Donaldo Colosio was assassinated. Ernesto Zedillo replaced him and in December, weeks into his first term, stunned Mexico and threw the economy into chaos by devaluing the peso because his predecessor, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, had depleted Mexico’s foreign exchange holdings. Stocks fell; Mexico’s importance was evident in global efforts to support its currency.

In 1997, the long reign of the PRI ended when it lost its majority in the lower house of the Mexican Congress. Political analysts declared it a sign that Mexico’s political system was moving toward an authentic multiparty system and predicted the PRI would lose the 2000 election. Vicente Fox, of the National Action Party (Partido de Acción Nacional, or PAN), was elected on a platform of ending government corruption and strengthening the economy. He was president until 2006 and focused on improving trade with the United States and addressing corruption, crime and the drug trade.

Mr. Fox was succeeded by PAN’s Felipe Calderón, who promised to be the “jobs president.” He worked to reform Mexico’s judicial system, increase employment and fight crime and drug cartels. The country remained in a recession with high unemployment and escalating cartel violence.

Enrique Peña Nieto brought the PRI back to power in 2012, assuming the presidency on Dec. 1. He was soon beset by protests, criticism and accusations that the party’s repression would return.

Life in Mexico today is unbalanced. Standards of living are higher in the north than the rural south. Although Mexico’s economy is the world’s 14th largest, 40 percent of the population lives in poverty. The rates of infant mortality and of nutritional and infectious diseases are high. The proportion of the GDP spent on health services has increased, but it is still lower than in 1960. The country opened its economy when it joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in 1985 and since, NAFTA has established agreements with other markets including the European Union and Japan. However, Mexico still has many internal problems to address.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky is a writer from Alberta.