Ministers’ Conference in 1944.

Canada didn’t leap to send a diplomat to Britain immediately following Confederation. After all, communicating with Ottawa and London on matters affecting the new Dominion was the job of the governor general. But in 1869, Sir John A. Macdonald picked Sir John Rose, a Montreal banker and railway magnate, to be, not an orthodox diplomat, but what his new hosts tactfully called “a Gentleman enjoying the confidence of the Canadian Government.” Later, he was given the title “financial commissioner.” As was common among diplomats in the 19th Century, he conducted his own private and highly profitable dealings while also negotiating various agreements and promoting emigration. So skilled was he at insinuating himself into British society that he became the financial adviser to the Prince of Wales (the eventual Edward VII).

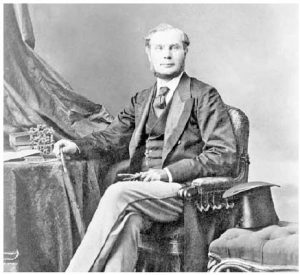

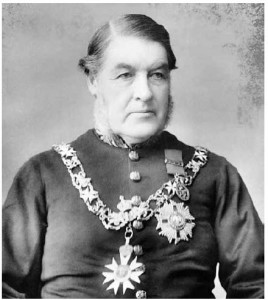

By 1880, both countries felt their relationship needed to be put on a more sophisticated footing, and Macdonald appointed Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt, another railway man and one of Macdonald’s fellow Fathers of Confederation, to run his London-based diplomatic commission. There arose the question of what the new institution should be called. As Canada wasn’t a foreign country, “embassy” was out of the question, as was “legation.” The two sides came up the more familial-sounding “high commission” and the other dominions followed suit: New Zealand in 1905, Australia in 1910, and South Africa in 1911.

One result of the Great War (1914-18) was that many such states, having fought beside the Mother Country, grew increasingly nationalistic and demanded greater say in their own international relations. The Balfour Declaration of 1926 established, among other things, that governors general were not representing the British government, but rather the monarch. This led Britain to start appointing high commissioners of its own — to Canada in 1928, South Africa in 1930, Australia in 1930, New Zealand in 1936. Since 1938, when South Africa sent a high commissioner of its own to Canada, such diplomatic reciprocity has prevailed in many, but not all, the countries of the Commonwealth, which now has 54 members.

Canada has had between 26 and 28 high commissioners in London, depending on how you count one who was “acting,” but never confirmed and another, Norman Robertson, who held the position twice. Some, such as Robertson and Charles Ritchie, were career foreign service officers; diplomacy was their profession. Most high commissioners, however, have been former federal or provincial politicians, though not always members of the same party as the prime ministers who selected them. Paul Martin Sr. (served 1974-79) is an instance of one drawn from the national stage; Roy McMurtry of Ontario (1985-88) an example of one from the provincial. To a remarkable degree, all of them faced many of the same hurdles, though that’s not to deny that times changed.

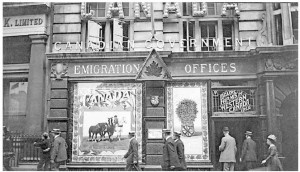

Early commissioners were often busy convincing rich individuals to help finance construction of Canada’s railways and enticing poor ones to fill up the

immense areas of the Prairies and West that the railways had made accessible. (Galt, to his credit, arranged for the arrival of thousands of Jews from Russia where they were miserably mistreated.) Trade matters were the other abiding concern. What Canada had to sell, other than hard commodities, was food. For generations, however, Britain banned the importation of, for example,

Canadian beef, a fact that led Galt’s successor, Sir Charles Tupper (1883-96), a financier and former cabinet minister, to fight back in an unusual fashion. When the British denied entry to yet another herd of Canadian cattle, claiming the creatures were diseased, Tupper, who was an MD as well as an MP, personally and publicly autopsied some of the animals to prove that they carried no pathogens. (Brilliant publicity, but the dispute remained unresolved for several more years.)

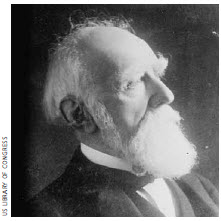

The length of the high commissioners’ tenures varies considerably; one recent holder of the office, Jeremy Kinsman, a career diplomat, presided only from 2000 to 2002. Far and away the longest-serving was the redoubtable Donald Smith, the driver of the CPR’s Last Spike. He started out as a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader and became a capitalist extraordinaire. “It was a great advantage to have a rich man in the post,” a biographer wrote when Sir Donald, as he then was, became commissioner in 1896 (two years before being elevated to the peerage as Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal). He was the staunchest of imperialists, fearsome-looking and close-mouthed, without Tupper’s subtlety or flair. Instead, he had longevity, professionally and literally. Born the year George III died, he lived to the eve of the First World War. In the last period of his life, back in his Montreal mansion, he entertained, by his own count, 21 earls, half a dozen viscounts, eight dukes, seven marquises, a royal prince and princess and one future king and queen. His fellow barons were evidently too numerous or humble to tabulate.

The names of some high commissioners of recent years will stir an assortment of memories. The late Jean Casselman Wadds (1980-83) was only the third woman to be elected to the House of Commons and remains Canada’s only female high commissioner to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, to use the formal job title. Her successor, the late Donald Jamieson (1983-85), was a Newfoundland broadcaster. He served in Pierre Trudeau’s cabinet — as did Donald Stovel Macdonald (1988-91), Liberal MP for Rosedale. Fredrik Stefan Eaton (1991-94) was the president, chairman and CEO of the soon-to-be-bankrupt T. Eaton & Co., the firm founded by his great-grandfather. He preceded the late Royce Frith (1994-96), another Trudeau-era

Liberal, renowned for his charm and bonhomie, who became high commissioner after his time as minority leader of the Senate. Mel Cappe was a diplomatic professional with wide experience who served in London from 2002-06 and is now the CEO of the Canadian Institute for Research on Public Policy. His place was assumed by James R. Wright (2006-11), diplomat and civil servant — the predecessor of the current high commissioner, Gordon Campbell.

– GF