In 1925, Britain’s economically inexperienced chancellor of the exchequer, agonizing over the economic controversy of the day, returned Britain to the gold standard. The decision was hailed as a triumph of sound economics, necessary to protect sterling and London’s status as the world’s financial centre.

Disaster followed. The Great Depression arrived half a decade earlier in Britain than elsewhere. Chancellor Winston Churchill came to regard his decision as the worst of his career — and he made a few doozies during the course of a long life. So it might be a surprise that in 2002 the best minds in Europe launched a similar mistake, the euro.

But how can these be similar mistakes? During the last U.S. presidential race Ron Paul argued that the United States needed to return to the gold standard to avoid financial crises, like the one in the Eurozone.

Britain returned to the gold standard at pre-First World War parity, effectively, US$4.866 for £1, an overvaluation of the pound to start with. Then bad things happened. Britain’s gold reserves were relatively low; France and the United States controlled three-quarters of the world’s gold supply. This drove up gold prices and dragged up sterling, now yoked to gold.

Britain returned to the gold standard at pre-First World War parity, effectively, US$4.866 for £1, an overvaluation of the pound to start with. Then bad things happened. Britain’s gold reserves were relatively low; France and the United States controlled three-quarters of the world’s gold supply. This drove up gold prices and dragged up sterling, now yoked to gold.

Deflation and wage reduction — challenges facing much of southern Europe today — were the only way for Britain to remain competitive, with more deflation needed every day as gold rose in value. Workers resisted wage cuts. British competitiveness collapsed. Unemployment and government debt soared as the economy went in the other direction. Britain dropped the gold standard in 1931, but by then much of the world was in Depression.

In 1963, Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz wrote a groundbreaking study that fingered the U.S. Federal Reserve as the prime villain of the U.S. Great Depression. The Fed restricted money supply, just as the gold standard did in Britain, driving both bank collapse and deflation, made all the worse by a deliberate policy to keep wages high to encourage consumption. Artificially higher wages meant many fewer jobs and much less consumption.

In 1963, Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz wrote a groundbreaking study that fingered the U.S. Federal Reserve as the prime villain of the U.S. Great Depression. The Fed restricted money supply, just as the gold standard did in Britain, driving both bank collapse and deflation, made all the worse by a deliberate policy to keep wages high to encourage consumption. Artificially higher wages meant many fewer jobs and much less consumption.

The euro is doing the same nasty trick for southern Europe. Media reports focus on the various versions of the private and public sector financial crises in the area, but these have only lifted the veil on the underlying problems — otherwise, these crises would not be near as severe. Instead of being hung on a cross of gold or crucified by the Fed, nations like Greece are hoisted on a petard of euros, which leaves their economies uncompetitive.

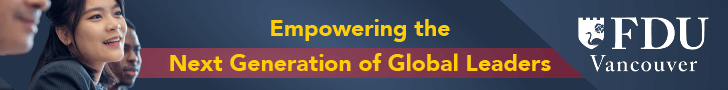

Here’s why. German wage costs have held steady since the introduction of the euro, as seen in Figure 1. Southern European wage costs have soared. Thus, due to wage increases, businesses in southern Europe have been saddled with higher costs compared to Germany, reducing the competitiveness of southern Europe compared to Germany. If two businesses are in competition and one sees wage costs rise and the other doesn’t, then the first has a competitiveness problem.

Here’s why. German wage costs have held steady since the introduction of the euro, as seen in Figure 1. Southern European wage costs have soared. Thus, due to wage increases, businesses in southern Europe have been saddled with higher costs compared to Germany, reducing the competitiveness of southern Europe compared to Germany. If two businesses are in competition and one sees wage costs rise and the other doesn’t, then the first has a competitiveness problem.

If southern European economies had their own currency, then they could devalue their currency and remain competitive. But these nations are tied to the euro (as Britain was to the gold standard) and thus they cannot devalue compared to Germany. Their only route to a return to competitiveness is domestic deflation, particularly wage deflation. But this is difficult, as Britain learned when it returned to the gold standard.

The drachma/euro exchange rate was set in 2000; Greece had been late to the negotiations and the rates for the other 11 original members of the Eurozone were set two years earlier, with new euro notes replacing national currencies in 2002. Assume that the drachma, the lira, and other southern currencies were taken into the euro at appropriate values and then consider what has happened since.

The drachma/euro exchange rate was set in 2000; Greece had been late to the negotiations and the rates for the other 11 original members of the Eurozone were set two years earlier, with new euro notes replacing national currencies in 2002. Assume that the drachma, the lira, and other southern currencies were taken into the euro at appropriate values and then consider what has happened since.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of European unit labour cost (ULC), a combination of pay and productivity since 2000, by which point the exchange rates for the original 12 were set. It immediately becomes apparent there are two Europes — Germany and the rest. While the media tend to focus on Greece and other southern nations on one extreme and Germany on the other, the other original 12 countries, with the partial exception of Austria (where ULC had increased by only three percent by 2007), are clearly much closer to Greece than Germany. Now, France and Italy have huge challenges to meet.

With separate exchange rates, changes in labour costs and other factors that affect the competitiveness of exports would be offset by changes in the value of currencies.

With separate exchange rates, changes in labour costs and other factors that affect the competitiveness of exports would be offset by changes in the value of currencies.

But, just as a Britain yoked to the gold standard in 1925 was trapped with an unrealistic value for its currency, non-German nations are yoked to the euro standard. Because Germany has held wage costs in line with productivity growth and the other European nations haven’t, the euro in these nations is effectively overvalued, while Germany has a massively undervalued currency (in some ways, like China’s) gridding its competitiveness in Europe and undermining everyone else’s.

In 2007, at the beginning of the current crisis, Germany’s ULC was actually five percent lower than in 2000, while the southern European economies were nearly 20 percent higher — in other words, a competitiveness shift of about 25 percent with no offsetting devaluation possible. No wonder Germany is the world’s greatest exporter, surpassing even China. To become competitive, other European nations would have to undergo massive wage and cost deflation — the same situation Britain faced after 1925.

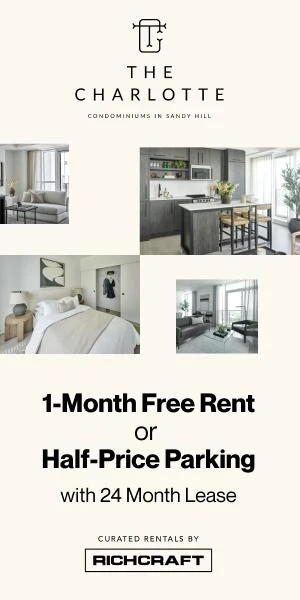

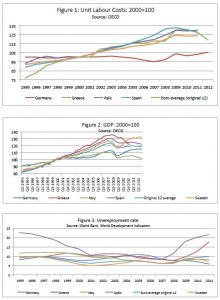

The consequences have been devastating. Figure 2 shows GDP growth over the period of the euro, with 2000 set equal to 100, and the disastrous falloff since the onset of the crisis. Figures 3 and 4 show the historical data on overall unemployment and youth unemployment. Figure 5 shows the most current data on unemployment, with the original euro 12 average replaced by the current euro 17 as this figure is limited to current data.

The underlying crisis may be spreading. France is in recession. As Europe weakens, so does Germany’s export machine. The German economy declined by 0.7 percent in the last quarter of 2012 and grew by only 0.1 percent in the first quarter of this year.

Readers who look at the charts closely will note something interesting happened with the German economy in the mid-2000s. That, and why Sweden is included in these charts, will be discussed later.

The muddle-through steamroller

When the Euro crisis first struck, Germany took a strict line with Greece, while France sought more help for the struggling EU member. A French friend of mine explained: “You North Americans just don’t understand how generous the French are” …pause… “with German money.”

As competitiveness problems spread through southern Europe and up to France, there won’t be enough German money to go around. The response has been Germany’s muddle-through steamroller. Germany provides just enough money to handle the various crises, but steamrolls through demands to throw enough money at the immediate problems to solve them or to just let southern Europe go.

Yet voices are already saying the euro crisis is dissipating. But, at best, this fully applies only to the immediate problems — government overspending and banking crises. These are detached from the underlying problem of this misshapen currency union. Banks can be rescued (or hived off as “bad” banks), creditors shorted and government supported by the European Central Bank, all underpinned with Germany — but none of this solves the imbalance in Europe.

The exit fix

Surprisingly, a move to allow a Euro breakup may be the solution to saving the euro area largely as is.

Economists refer to “optimal currency areas.” Being economists, they seldom mean exactly the same thing by this, but fundamentally it applies to an area with a similar economic structure and wealth, with a free flow of capital and people. It would take far too long to go on in detail, but let’s just say that Germany and Greece no more form an optimal currency area because they are in Europe than do Switzerland and Nepal just because they both have really big mountains.

So long as the current imbalances in competitiveness exist, there are four solutions: 1) Germany can establish a permanently replenished special fund to allow the rest of Europe to buy its goods; or 2) members of the EU may take the necessary reforms to create a viable currency area, with all nations competitive over the long term and increased German consumption; or 3) nations that don’t fit the Eurozone may be asked to leave (or may themselves ask to leave). Or 4) maybe it’s just time to drop the euro.

The first isn’t going to happen. For the second to happen, it is likely necessary to start on the third, to give more urgency to the need for reforms. European leaders need to begin working on a plan to devolve nations out of the euro when a semblance of stability returns to Europe. It is dangerous to dismantle a building in the middle of a hurricane. But there is some chance of a calm-down. Figure 1 shows signs of adjustment in competitiveness in the south. Already occurring negative growth and soaring unemployment in the south would pre-empt some of the pain of devolution — the hurricane has already made a good start on demolishing the house. In other words, if we get a breather from the hurricane, breaking some nations out of the EU may become feasible.

Then the question becomes which nations could fit into, if not an optimal currency area, then at least a tolerable currency area. Germany might move closer to the rest of Europe and see domestic consumption rise, given the unsustainability of its export model (like Japan before it and now China), while other European nations could become a bit more German. Or perhaps, Germany, as the outrider, should leave, with a highly appreciated Deutschmark, though Germany’s departure is not likely politically possible.

Oskar Lafontaine, a leftist politician and German finance minister who launched the euro, thinks it’s time to give up on the EU. “Hopes that the creation of the euro would force rational economic behaviour on all sides were in vain,” he said, adding it was a “catastrophe” to believe southern nations could make the reforms required to be competitive within a single currency. (Evans-Pritchard, 2013)

The political muscle required to enact the reforms necessary to maintain the EU intact would be much strengthened by a credible ejection/withdrawal threat. Even nations loaded with extraordinarily painful and unpopular reforms have shown no taste for a EU exit — but many have shown a preference for watering down the reforms. The real threat of ejection could concentrate the mind of those who wish neither to leave the EU nor undertake the necessary reforms to maintain a truly viable currency area.

In other words, developing an exit mechanism is the essential reform, the threat of which, in turn, makes more likely the reforms that could mean the exit mechanism is unneeded.

The staying-in fix

Britain on the gold standard was never able to manage the deflation and increased competitiveness required for economic health. However, a number of reforms could help make non-German economies more competitive, draw in investment and help with wage reduction.

The media are full of how badly the European periphery is doing, but one periphery is doing just fine, thank you. The Nordic countries are the new free market champions. Well, actually, despite all you read about the “social democratic” Nordic zone, particularly Sweden, the Nordic countries — including Sweden — have always been free market champions.

Free markets involve much more than small government. They also require the rule of law to protect property, contracting and the politically weak from the politically powerful in the marketplace; sound money to defend the value of property held in monetary instruments, including wages; freedom to trade; and reasonable regulations that allow the entrepreneurial spirit of free markets to thrive. In all these areas, except size of government, Nordic nations, and especially Sweden, have been strong.

Size of government remains important. If government is too large, it squeezes out free exchange and entrepreneurial efforts to build wealth. At the height of Sweden’s welfare state, government spending was equal to 70 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Government remains too large in much of Europe, and leaving aside the arguments about how much to cut now and how much to cut later, in the long run most European nations would do well to follow the examples of the most radically “right-wing” cutters of government.

No, I am not talking about the milquetoast policies of Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan — I am talking real radical Tea Party stuff, like that of Jean Chrétien in Canada, social democratic chancellor Gerhard Schröder in Germany, and both social democratic and centre-right parties in Sweden, albeit rather more enthusiastically under Sweden’s centre-right parties.

Figure 6 sets the size of government to 100 at the beginning of reform: 1979-90 for Britain’s Thatcher era; 1980-88 for the United States, when Reagan was president; and 1993-2003 for Canada, when Chrétien was in power. For Germany and Sweden, 100 is set to 1995 and 1993 respectively as these nations moved to get public spending under control. Since reform in these nations is less tied to particular heads of government, the time series continue through more than one administration.

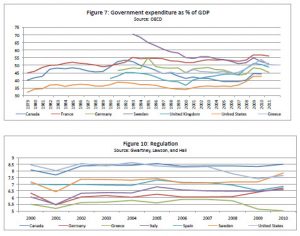

Figure 7 shows government expenditure as a percentage of GDP and includes France as an example of a country moving in the wrong direction. All the nations had an uptick in spending as a percentage of GDP with the onset of the crisis and all have moved to try to control spending, with varying degrees of vigour, since then. Sweden, despite large cuts, still maintains a big government, but one moving in the right direction. The Economist suggests that Sweden may soon have a proportionately smaller government than the United Kingdom.

Smaller government also reduces domestic pressure on costs and opens more of the economy to making exportable goods — in other words, it is a step towards greater competitiveness and towards creating a more viable currency area for southern European nations.

A smaller government that can pay its bills is something that should be desired by everyone from fiscal conservatives to Keynesians (or at least those Keynesians who actually understand Keynes). Keynes believed in modest, bill-paying government in normal times, with significant deficits allowed only in strained economic times to spur demand.

Whether Keynesian economics effectively stimulates the economy in a downturn remains a big debate in economics (and I personally don’t think it does) but virtually all can agree that it is better to cut in good times than bad. Governments that spend stupidly during the good times leave the cupboard bare in bad times. So, while short-term prescriptions differ, the ultimate aim should be smaller, fiscally balanced government that leaves room for the private sector to generate prosperity.

While regulation, education, and the retirement age are all far too complicated to discuss in detail, it is at least possible to point to the right direction in all three, again with the Nordic states, represented by Sweden, aligned to this direction.

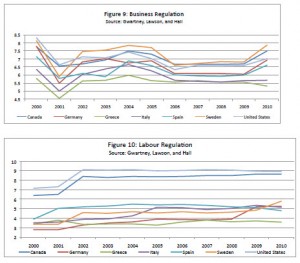

Growth-throttling regulation needs to be brought under control, particularly in labour markets that keep those who most need jobs, particularly the youth, out of work. Figures 8 to 10 explore the state of regulation, though data are available only to 2010. Regulation is scored on a 0-10 scale, with 10 being the most free market-

friendly regulation.

For all regulation, Figure 8, as expected from the preceding discussion, Sweden and Germany have started to move in the right direction, while Greece is only getting worse. Figure 9 on business regulation may shock those who have believed the myth of socialist Sweden. Since the early part of the opening decade of this century, Sweden has led our selected group in the friendliness of its business regulation, with, again, Germany and Sweden showing the most improvement and Greece, in this instance, the worst.

Labour market regulation, Figure 10, presents the greatest challenge and opportunity for Europe. Canada and the United States are far ahead in labour regulation, though German and, even more impressively, Swedish reforms are leading to improvements.

Germany’s labour market reforms under Chancellor Schröder in 2003 combined unemployment and welfare benefits to reduce incentives not to work and increase incentives to work, perhaps the key part of the reform package and not fully captured in Figure 10. This is politically very difficult, as Canadian politicians who have attempted to reform employment insurance have discovered. Chrétien, so good on the budget, also wanted to be good on this issue, but had to retreat on employment insurance reforms for the 1997 election because of the politics of EI in Atlantic Canada, but it still cost him all but a handful of seats there.

Retirement systems also need to be brought in line. Germans were distressed to learn in the early part of the crisis that their money was subsidizing an earlier retirement in Greece than in Germany. Reform is needed to stabilize overall government expenditures, too, given the aging of Europe. Here, Sweden may be leading the way, with automatic adjustments for longer life expectancy.

Europe also needs education system improvement. Too many Europeans are being poorly served by public school systems and universities that do not provide needed skills for the workplace. Again, Sweden and Germany lead the way. Sweden now has a universal system of school vouchers and has opened the door to private schools to compete with public ones; plus, youth in Sweden can leave an often failing public system and get the skills they need in a market-based education system. The competition also improves the public system. Germany has long had a tight system of co-operation between skills-development educational institutions and business.

Getting to a viable currency area

Now a brief segue back to Figure 1 on ULC and Figures 2, 3, and 4 on GDP and unemployment. A careful look will show that Germany’s success in all these areas really only took off after the 2003 reforms.

“When the euro was introduced, Germany was dubbed the ‘sick man of Europe,’ with low growth rates and high unemployment. However, it is now enjoying a relatively low jobless rate of 7.2 percent and has escaped recession unlike much of the Eurozone,” as Rachel Cooper recently discussed in The Telegraph.

Germany’s ability to reform gives hope that similar reforms elsewhere in Europe could work. We began with Britain’s need for wage reduction under the gold standard. Germany effectively performed this trick in the mid-2000s through a combination of productivity growth and wage restraint, as seen in Figure 1.

The reforms listed above would all move southern Europe in that direction. A flexible labour market makes wage restraint easier. Smaller government lessens the tax burden on the private sector and increases the space for wealth creation, aiding competitiveness. Regulatory reform, pension reform and education reform lead to a freer economy, drawing in investment and productivity growth.

Such a comprehensive package of reforms over time could moderate wages while increasing productivity, creating effective wage deflation if productivity growth exceeds wage growth. This would help balance the Eurozone area by giving Germans reasons to consume European products, hopefully also boosting German consumption. That would spark southern growth while potentially saving Germany from a Japanese-like crisis.

Fred McMahon is the Michael Walker chair of economic freedom research at the Fraser Institute. He thanks Fraser Institute senior fellow Alan Dowd for his important comments in reviewing this article.