Globally, the number of land animals killed each year for food exceeds 65 billion, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. In the United States alone, 10 billion land animals are killed for food. In Canada, the number is 700 million. These statistics are unfathomable — a bit like the national debt. Standards for the treatment of these sentient creatures vary greatly among nations.

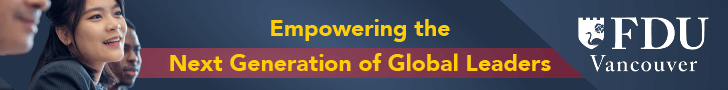

The European Union and its member nations are the most progressive, with Canada lagging on the humaneness scale. With pressure from consumer and corporate initiatives, this may change. For example, eight major Canadian grocers recently announced they would not buy pork — as of 2022 — from farmers who confine their pregnant pigs for four months in steel and concrete gestation cages, unable to walk or turn around. Canada’s million-plus female breeding pigs spend their adult lives so intensively confined, they suffer physical and mental pain. After 2022, sows will still be confined for between two and three weeks in farrowing crates, which are similar steel cages for birthing and nursing piglets, because the grocers have, so far, only dealt with gestation stalls.

Canada’s federal government has lacked leadership in farm animal welfare, with no national policy that includes compliance tools or penalties when the codes of practice are not followed. The majority of Canada’s farm animals exist in “factory farm” conditions, where animals are seen as production units and receive the least possible space for the shortest time and the least amount of feed. Producers are caught in a catch-22 because they’re under pressure to supply animal products at rock-bottom prices to meet demand for cheap food. These methods of production are deemed economical, unless the human and animal health and welfare and environmental costs are also measured.

Ian Duncan, professor emeritus in animal science at the University of Guelph, told Diplomat: “Cheap food seems to be part of the mantra since World War II, with ever-more-efficient systems. But when it comes to animal production, the cost is being paid by the animals. Animals are being kept in worse and worse conditions. We’re now spending less than 10 percent of our income on food. Milk is now cheaper than bottled water.

“Cheap food, such as the 99-cent burger, has health implications for chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer and infectious diseases like influenza,” says Michael Greger, MD, director of public health and animal agriculture at Humane Society International. “A diet high in cheap animal products has other costs externalized by society. Such food is not cheap if environmental degradations are included. Yet these foods are cheap at purchase point, so people consume lots of them.”

Sows are tightly confined as are 95 percent of Canada’s egg-laying hens, in their case, in small “battery” cages, stacked many levels high. Each hen has a space approximately the size of a mouse pad, with no amenities to nest, perch, dust bathe or move away from other birds — all important needs. The hens’ beaks are cut to thwart damage to other birds in crowded cages.

As with most surgical procedures related to raising food animals — castration, hot-iron branding, beak-trimming, tail-cutting — the animal is given no painkiller.

Dr. Duncan notes: “Producers’ husbandry skills have been lost in the last 40 to 60 years. It’s very sad.” It will require re-learning those skills to allow animals greater freedom in the future.

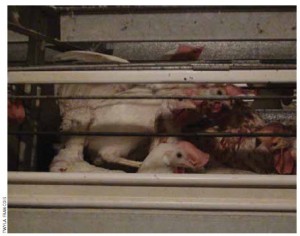

Dairy cows are impregnated annually to produce milk to be redirected to humans. The cow’s calf is taken from her within hours of birth — causing emotional pain for both, given the mammalian bond between parent and offspring. The calf receives artificial formula and is usually reared in solitary confinement, later to join the milking herd, or if male, to be sold as veal. The regimen of high milk and calf production takes a heavy toll on the cow, so after four or five years, she is burned out, perilously thin, and shipped to slaughter — to become lean hamburger meat as she lacks enough body fat for marbled beef.

Meat chickens, known as broilers, typically live less than five weeks in tremendously crowded barns, air thick with ammonia from accumulated manure. They are little more than chicks when slaughtered. Genetically selected to grow at phenomenal rates, these birds are given antibiotics to speed growth and keep them alive under unsanitary and stressful conditions. Their feed typically includes rendered animal body parts. (Rendered parts from yesterday’s slaughter animals routinely are fed back to living animals, many of them vegetarian by nature. It’s how the meat industry rids itself of mountains of unwanted body parts and blood. It’s also how “mad cow” disease inadvertently spread among Canadian cattle in 2003.)

Canadian beef calves are branded or marked for identification, dehorned and castrated. Most Canadian cattle graze on pasture part of their lives, but weeks before slaughter they are shipped to crowded, muddy feed lots for “finishing” — quick fattening — on high-protein feed such as corn, which ruminants cannot easily digest. The indigestible diet causes liver abscesses, which are cut from the carcass at slaughter.

Pigs are a highly intelligent and social species. Current standards allow castration and tail-cutting of piglets without pain relief, yet it costs only 22¢ per painkiller dose for piglet castration, according to the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture. (Farmers say tail-cutting is necessary to prevent infection from bites from other pigs, though it can be argued that the behaviour is due to boredom because of the pigs’ living conditions.)

Breeding sows are intensively confined in gestation and farrowing (birthing) crates, unable to turn around. When sows wear out after four years or so, they are shipped to slaughter to become cold cuts and sausage. Their meat so depleted that it is only fit as such processed meat. Their progeny, market pigs, are given antibiotics to speed growth — valuable drugs for humans and animals that lose their effectiveness against microbial diseases from antibiotic overuse in farm animals. Pig feed, too, typically contains rendered animal parts.

EU legislation for farm animals

Why is the European Union so progressive toward farm animals? Its citizens have demanded it. Dr. Duncan notes, too, that animal-welfare experts develop EU standards. Legislation to protect farm animals is based on the premise that animals are sentient beings. As logical and accurate as that is, it’s not a concept followed in many countries, including Canada.

EU legislation is based on the Five Freedoms, a standard developed in the United Kingdom, and intended to meet animals’ physiological and behavioural needs. They include:

• Freedom from thirst, hunger and malnutrition (to maintain full health and vigour)

• Freedom from discomfort (includes shelter and rest area)

• Freedom from pain, injury and disease (by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment)

• Freedom to express normal behaviour (sufficient space, proper facilities and company of the animals’ own kind)

• Freedom from fear and distress (ensuring conditions that avoid mental suffering).

In Canada, there are no federal or provincial laws to protect farm animals from established confinement practices, nor has Canada adopted the Five Freedoms. Canada lacks a national farm-animal policy, according to David Fraser, professor in the animal welfare program at the University of British Columbia and co-ordinator of a 2012 report titled, A National Farm Animal Welfare System for Canada, which he produced for the National Farm Animal Health and Welfare Council, a new agency funded by federal and provincial governments and industry. The council’s vision is lofty: “For Canada to have a comprehensive farm-animal welfare system that ensures the welfare of farm animals, reflects Canadian values, involves national standards that are informed by timely scientific research and includes a suite of compliance tools and activities sufficient to ensure domestic and international confidence in the welfare of farm animals in Canada.”

It remains to be seen if the vision will be fulfilled, whether driven by consumer demand for more humane treatment, by industry or by government. The report notes the “possible future difficulty accessing certain markets” without such a system.

Currently, Canadian voluntary (that is, non-legislated) codes of practice set standards for the treatment of farmed animals, but many have been outdated by decades. Funded by the federal government, the codes are co-ordinated by the National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC), an organization dominated by industry interests with limited representation from animal-protection organizations — though the focus is welfare. The welfare representative on code committees is selected from only one organization, to the exclusion of all other animal-protection organizations. The code development process now includes a science-informed direction.

Animals are considered property under the law in Canada and may be treated more as machines than as sentient beings. Enforcement of codes is non-existent at present and some producers admit they have not read the code for the animals they keep. Canada’s new five-year agriculture policy, Growing Forward II, does not include funding provisions for producers to upgrade facilities for improved animal welfare.

A premise in EU policy is that animal health and welfare are inextricably linked — that when one suffers, both do, including food safety. The EU bases farm-animal legislation on high welfare standards to raise the bar and not to economically disadvantage member nations that meet high welfare standards.

What do more humanely produced animal products cost? Socio-economic data prepared by the European Commission show production of a free-range egg costs just 2.6 eurocents (Cdn $.035) more to produce than a battery egg, while a free-run (barn) egg costs 1.3 eurocents (Cdn $.0178) more. Housing sows in groups rather than stalls adds just 1 to 2 eurocents to the cost of producing one kilogram of pork.

Health matters

How healthy are Canadian animal products when animal welfare is given short shrift? The EU banned imports of Canadian beef because it deems implanted growth hormones unsafe. To produce docile animals, Canadian beef cattle undergo surgical castration, without anesthetic, only to undergo a second compensating procedure. They are implanted with growth hormones (six are government-approved for use) to speed growth slowed by their castration.

Canada and the United States allow use of ractopamine, a food additive marketed as “Paylean,” intended to produce lean meat and speed growth in pigs. The FDA in the U.S. and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency also allow use of Paylean in turkeys and (under Merck’s trade name Optaflexx) in beef cattle.

Russia, China and 160 other nations banned its use and banned most imported Canadian pork because of Paylean. Mexico and Brazil are among 26 countries that allow use of the additive.

Studies on pigs given Paylean, especially those subjected to the stress of transport, showed that they suffer increased injury, quickened heart rates, lameness, aggression and death.

If an animal is sick or injured when it leaves the farm, transport conditions in Canada can only exacerbate those conditions. Comparing Canadian trucks to those in the EU, Luigi Faucitano, an animal scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada who specializes in pigs, notes a critical difference in Canadian vehicles compared with those in the EU: Canadian trucks don’t have mechanical ventilation.

“In the EU, ventilation is managed by the driver,” he says. “It’s an example for Canada to follow. No [pig] trucks in North America have mechanical ventilation, which is very important.”

Commenting on the duration of rest periods during travel, Dr. Faucitano says: “Five hours rest for pvigs [after long transport] is too short to be fit to travel again.” He adds that some trucks with multi-levels have ramps too steep for pigs to climb. “A solution is hydraulic systems which raise and lower whole floors of pigs in the truck.”

“Research in swine transport is very recent,” he points out. “Many recommendations in the [NFACC] codes must be validated with science. An example is densities, where all our current recommendations are from the EU and the U.S. — but their recommendations usually relate to warm temperatures, not the cold temperatures in Canada.”

Consumer and corporate influences

Consumers value well-being for farmed animals once they understand the intensive confinement of factory farming. Canadian food retailers, including eight major grocers, Tim Hortons, plus 100 other Canadian restaurants, have taken a stand, setting benchmarks to end sow stalls.

It’s not only ethical treatment of farm animals that concerns consumers, but the tie between animal health and welfare and food safety. What happens to animals also affects humans; it affects our environment and our health, including failed antibiotics.

Canadian scientists Rebecca Irwin of Public Health Canada and Scott McEwen of the Ontario Veterinary College are signatories to a letter published in the August issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, calling for a worldwide ban on use of third-generation cephalosporin drugs in poultry. The drug is commonly used to fight bloodstream infections in humans caused by drug resistant E. coli, which can be transmitted to humans from animals. Meanwhile, this important drug is widely used sub-therapeutically in Canadian poultry as a growth promoter.

The authors report unnecessary deaths from drug-resistant infections and increased hospital stays, with extrapolations to all of Europe of 1,518 additional deaths and 67,236 days of hospital admissions as a result of cephalosporin and other antimicrobial drug use in poultry. The authors conclude: “The number of avoidable deaths and the costs of health care potentially caused by third-generation cephalosporin use in food animals are staggering.”

McDonald’s serves 69 million customers daily in more than 100 countries and is the largest procurer of beef in the world, by volume. Bruce Feinberg, senior director of global quality for McDonald’s worldwide supply chain management, told a Calgary audience recently that a key moment for McDonald’s came when a consumer survey showed when “animal welfare” was paired with “health”— as in health and welfare — consumers drew a strong connection between the health of the animal and the quality and safety of the food product.

McDonald’s is a corporate leader in farm-animal welfare. For example, its space requirement for leghorn laying hens, the most commonly used breed, exceeds Canada’s voluntary standard. McDonald’s also requires an annual audit of slaughter plants that supply its meat. The program assesses percentages of animal vocalizations and falls suffered, and correct first-time stunning attempts (which stuns the animal, making it insentient before it is bled and killed) by slaughter plant workers, as part of a program developed by Temple Grandin, an internationally recognized animal expert affiliated with Colorado State University. Time magazine named her one of 2010’s 100 most influential people in the world.

Most consumers don’t want animals to suffer and can effectively take action to protect animals by cutting back or cutting out animal products, assuring a more ethical and environmentally friendly diet.

As countries make improvements to animal production standards — as the EU, Australia, New Zealand and some U.S. states have — trade sanctions could be in the offing for nations that lag behind, eventually forcing a move towards healthier and more humane farm animal conditions.

Stephanie Brown is co-founder and director of the Toronto-based Canadian Coalition for Farm Animals.