On Sept. 30, 2013, a Russian navy group returned to Severomorsk after a month-long voyage to the New Siberian Islands. The group included the heavy nuclear missile cruiser Peter the Great, landing and support vessels and four nuclear ice-breakers. The highlight of the exercise was a landing practice on the islands. This seems to be a faraway place, but it is not.

Alert, in Canada’s Queen Elizabeth Islands, is about 1,600 kilometres closer to the New Siberian Islands than to Ottawa. It is the height of the Syrian crisis, when almost everything still afloat in the Russian surface navy is rushing to the Middle East. The question is: Why is a powerful group of naval vessels being used to flex Russian military muscle beyond the Arctic Circle and to establish a permanent outpost at the New Siberian Islands?

As is typical with Russian politics, if you explore the matter long enough, sooner or later you will find oil interests at its heart. The Russian economy is driven by oil export. Total Russian exports for 2012 were $525 billion US, among which oil exceeded $180 billion, with another $130 billion in oil products — mostly furnace oil or even crude that has simply been re-labelled as oil product to circumvent the 66-percent export duty.

Together, this totals $310 billion, almost 60 percent of Russian exports. Add to this the $63 billion in revenue from the export of natural gas and the total comes to 71 percent.

Tax revenue from oil exports is a critical component of the state budget as well. The lion’s share of Russian oil and gas production comes from the Russian Far North, which is, without any hyperbole, the most critical region for the well-being of the country. This makes the North the land of Russia’s national interests, but it is not always national interests that drive Russian political decisions. The companies that develop the northern oil and gas resources are Gazprom, Rosneft and Novatec, along with some smaller players.

Gazprom is controlled by the government, and 10.74 percent of the government’s stock is held by the government-owned Rosneftegaz holding company, which also controls 75 percent of Rosneft. Moscow’s second most influential man, Igor Sechyn, is the president of Rosneft and Rosneftegaz.

On Sept. 27, 2013, Sechyn shared his dream with investment forum participants in Sochi, Russia: “I dream of drilling an exploration well in the Cara Sea and to discover a unique deposit that will hold 3.5 billion tonnes of liquid hydrocarbons and 11.4 trillion cubic metres of natural gas.” (our translation) Igor Sechyn is not a dreamer, so this dream is certainly backed by geological research and defines the future plans of Rosneft. Since the takeover of TNK-BP in 2012, Rosneft is producing approximately 4.32 million barrels of oil, gas and condensate per day.

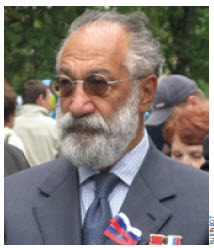

There was a time when Sechyn was almost unknown; at best he was referred to by insiders as “Putin’s shadow.” Now he is not only the most powerful man in the Russian energy sector, but also a political heavyweight and de-facto leader of the group of former KGB officers who currently run Russia. This group includes Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of the National Security Council, among many others.

Back in Soviet times, Patrushev was head of the counterintelligence directorate of the St. Petersburg KGB, while the young Igor Sechyn and Vladimir Putin worked in positions that were usually reserved for plainclothes KGB officers. Patrushev was behind the Arctic and Antarctic ventures of the Russian researcher and politician Arthur Chilingarov, including the infamous planting of the Russian flag at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. Patrushev and Chilingarov together took part in the 2007 helicopter landing at the South Pole; Chilingarov is an ideologist in terms of the development of the Russian North.

Gazprom is probably the most well-known Russian company. It is usually labelled as Putin’s energy weapon, and “Putin and Gazprom” are commonly seen by Europeans as two faces of the same bogeyman of gas from the east. It is almost true, but there is one more face to this creature: Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. Medvedev was a member of the board of Gazprom for eight years and its chairman for seven years and he still retains a special relationship with Gazprom.

As the company’s gas supply from old deposits gradually runs out, it has to move production further north. The latest addition is the Bovanenkovo gas field, which is about 400 kilometres above the Polar Circle, close to the west coast of the Yamal Peninsula. Bovanenkovo, with its reserves totalling 26.5 trillion cubic metres of gas and about 1.64 billion tons of oil and gas condensate, is the future supply base for the two Russian pipeline mega- projects, North Stream and South Stream, which are being built to bypass Ukraine (at least this is the official story).

According to the Pennsylvania-based consulting firm East European Gas Analysis, the real cost of South Stream, including the cost of the required new pipelines on Russian soil and the cost of the South Stream per se is more than $67 billion. A big part of this money has already been spent. The main beneficiaries of the supply and construction contracts for this mammoth project are Severstal, Strojtransgaz, Strojgaz-Consulting, and Strojgaz-Montazh. (By pure coincidence, all these companies are controlled by people who have alleged ties to Vladimir Putin).

Finally, Russia’s second biggest natural gas producer, Novatek, is developing Yamal-LNG projects on the east coast of the Yamal Peninsula. The privately held and well-run $6.9-billion company plans construction of the liquified natural gas plant in the Yamal permafrost zone, for export of LNG to China. The biggest shareholder of Novatek is the founder of Gunvor, commodity trader, Gennady Timchenko, who is also close to Vladimir Putin.

All these business ties point to one thing: In the Arctic, Russia’s national interests, and the business interests of the most influential Russian business and political elites, coincide. Russia is far down the road with development of the polar deposits of oil and gas and has passed the no-return point, even if it had such a contingency plan. The business interests of the powerful men in Russia and the need to get the return on the gigantic investment, require the Russian Federation to continue its northern expansion.

Opening the Doors for Co-operation

Back in 2006, Putin came up with the concept of “energy superpower” for Russia. It was kind of a healing balm for the ego of the Russians, many of whom still miss the status of political superpower, and a “feel good” euphemism for the resource-based economy that Russia had already become.

It was not just a PR facelift. The series of gas and oil wars with the Ukraine and Belarus followed: BP was muscled out from the Kovykta gas field; Shell lost control over the Sakhalin-2 project. The result of the energy ”superpower” policy was not amusing for Russia: Gazprom’s share in the European markets dropped, and development of the new oil and gas deposits slowed down because of the lack of foreign investment.

Now the superpower concept seems to have been silently shelved. Russia is opening its Arctic for co-operation. Italian Eni, French GDF and German Wintershall are partners in the South Stream. France’s TOTAL holds 25 percent of the Shtockman Development AG, which considers development of the Shtockman gas field in the Barents Sea. Novatek teamed up with TOTAL and China’s CNPC for Yamal LNG, and Rosneft teamed with Norway’s Statoil, Eni and Exxon-Mobil for three different Arctic shelf oilfields. Eni also participates in the Sever Energia gas producer, jointly with Rosneft, Novatek, and Gazprom’s subsidiary, Gazprom Neft. British Petroleum now controls 19.75 percent of Rosneft.

The Russian Federation is not the only country that looks at the Arctic as the region of the future. On Sept. 5, at the height of the Syrian crisis, U.S. President Barack Obama and the leaders of the Northern European countries met in Stockholm and agreed to combine their efforts in Arctic development.

Delivering the Goods

Most Russian oil and oil products are now exported via tankers from the Baltic, Black Sea and Pacific ports. The Black Sea route accounts for 35-40 percent of total Russian oil and oil products exports by sea. The Bosporus and Dardanelles straits are already at the limit of their capacity: the wait time for tankers before entering the straits is 70 hours or more. The situation is so bad that Russia even attempted to build Bosporus bypass oil pipelines Burgas-Alexandropulous and Samsun-Ceyhan. After passing Bosporus and Dardanelles straits, oil tankers bound for Far Eastern markets cross the Eastern Mediterranean, go through the Suez Channel and Red Sea, cross the Indian Ocean, pass the Strait of Malacca and only then reach their final destination. The 16,000-kilometre route from Novorossijsk to Vladivostok passes through politically unstable areas, takes more than two weeks, may be blocked if any of the brewing conflicts from Iran to Egypt and Syria, escalate, and Russia has no control over most of it. The route through the Panama Canal is even longer.

Meanwhile, there is a third option for Russia: the Northern Sea Way, 9,000 kilometres from Murmansk and along the Siberian coast, passing next to all the future oil- and gas-producing fields and under the protection of the Russian Northern Fleet. There is a catch, though. The longest open navigation period of the Northern Sea Way since it was reopened in 2010 lasted for just six months and the traffic was 110,000 tonnes. For the rest of the time, it was closed by ice. Nevertheless, Russia plans to expand its use. The total traffic by the Northern Sea Way reached 1.26 million tonnes for the first 10 months of 2013. The 2013 navigation also included a pilot shipment from China to Europe. To reach the goal of turning the Northern Sea Way into a major transportation route, Russia needs 512 new sea vessels by 2030. This program is beyond Russian shipyards’ capability, especially if one considers the needs of the Russian navy. Russian orders for ice-class vessels and ice-breakers from abroad are imminent, as Russia is determined to complete the entire program. So far, the winners of the big Russian shipbuilding contracts are only Korea and Japan.

The Military

There is one more dimension of the Russian Arctic expansion. Following the dissolution of the USSR, Russia lost its ability to use Ukrainian shipyards where the bulk of the Soviet blue water surface navy shipbuilding was concentrated. Russia’s navy was neglected and only nuclear missile submarines received minimal necessary maintenance.

Now, Russia is putting out a big effort to make up for lost time, but it is far behind. The resources of the Russian shipyards are insufficient to address the needs of the navy, the tanker fleet and growing international trade. This means that Russia needs to be able to manoeuvre its limited surface navy assets between Northern and Pacific theatres, and to protect the undefended coasts of Siberia, the Northern Sea Way, military bases and outposts, oil- and gas-producing regions and platforms from attack by sea from unauthorized landing, military or otherwise.

The goal of the September naval exercise was exactly that: to practise the use of the Russian northern fleet to protect remote islands and outposts along the Northern Sea Way, and possibly to transfer heavy surface assets between the two theatres. Russia also needs to have special Arctic-ready land forces, which it can use at remote outposts in the Arctic. Indeed the new Russian navy doctrine identifies defending the Polar regions as the main task of the Russian navy. This was always a priority, considering that Northern Sea fleet submarines, which are based in the Western Arctic, are the critical component of the Russian nuclear deterrent forces. The news in the navy doctrine is that the Russian navy now assumes responsibility for Russia’s entire northern coast.

The Russian navy and army closely co-ordinate Arctic plans. The 200th Independent Motorized Rifle Brigade, based near Murmansk, was reassigned to the Northern Fleet in 2012, and is undergoing a serious overhaul. It was once among the least combat-ready units of the Russian forces; now the training is intense.

There are plans to make 70 percent of its personnel professional. All positions in the brigade are filled, it is getting new tanks and will get special DT-30 Arctic personnel carriers, which are already on order from the Vityaz company. The brigade is being retrained for landing operations in Arctic conditions and will take care of the remote outposts on Novaya Zemlya islands and those further east.

Future plans include two new Arctic brigades by 2017. The specialized four-year officer training program for the Arctic motorized rifle brigades started at the Blagoveschensk Officers School in September 2013, so the 2017 date for the deployment of two new brigades is realistic.

The Russian Pacific Fleet may need reinforcement. It operates one Slava class missile cruiser, three Delta-III nuclear submarines (31 to 33 years old), six Oscar-II nuclear submarines (specially designed to combat carrier groups), seven Akula nuclear submarines, three destroyers and smaller vessels. All nuclear submarines are based on Kamchatka Vilyuchinsk/Krasheninnikov Bay base.

The Delta-III submarines need urgent replacement; they are too old. The plan is to have at least three new Borei class missile submarines carrying new Bulava SS-N-30 SLBM to replace the Delta-IIIs before 2020. After the replacement is complete, the number of warheads in the Pacific theatre will double, from the current 144 to 288.

The plans for empowering the Pacific fleet go further. In 2011, Russia signed a contract with France to manufacture two amphibious assault ships, Mistrals, for the Russian navy, and to license production of two more. The 32,000-tonne DWT (deadweight tonnage) vessels can carry up to 30 Ka-52 attack helicopters and a 450-n landing party and have a 17,200-kilometre range. Two of the Russian Mistrals are scheduled for Kamchatka deployment as well.

Finally, the sistership of the Peter the Great, the heavy-missile cruiser Admiral Nakhimov (Kirov class), was pulled out of the navy reserve and is undergoing a thorough overhaul. It has been a long process, but it is now well under way with a completion date scheduled for 2018. Admiral Nakhimov is to join the Pacific Fleet; it has to be based at Vilujsk as well, simply because it operates missiles similar to the ones used by Oscar-II and Vilujsk has all the necessary equipment to handle them.

This means that by the end of the decade, Russia will have a powerful navy group, based in the Northern Pacific that will have very strong landing operations capability and three Arctic brigades. The navy group will protect the Siberian coasts from the New Siberia Islands to the Bering Strait, Chukotka and Kamchatka. Meanwhile, the distance from Viluchinsk to the New Siberian Islands (the most eastern point of the September voyage of the Russian navy) is about 4,200 kilometres.

The same distance by sea separates Viluchinsk and Tuktoyaktuk in the Yukon. The amphibious Mistral assault vessel can cover this distance in five days. It will become clear where a ship is really heading only after it passes the Bering Strait. It will take the Mistral about two days either way from this point. There are no indications of aggressive Russian plans in the Northern Pacific and in the Beaufort Sea, but if such plans existed, Canada would have very little capability to counter them.

Currently an independent consultant, Dr. Zhalko-Tytarenko is the former head of the National Space Agency and member of National Disarmament Committee of Ukraine. He holds a PhD in physics.