It is an article of faith among large sections of the left-leaning intelligentsia that the United States invaded Iraq in 2003 simply to secure the country’s oil reserves. It’s one thing to hear this line from Noam Chomsky, but another thing to hear it from a figure such as Sir David King, Britain’s former chief scientific adviser to the government of Tony Blair. It was Blair, remember, who famously supported the U.S. invasion because Saddam Hussein’s regime allegedly possessed weapons of mass destruction, not oil wells.

While King never articulated this position when he held his old job, he was notably not alone. “It was certainly the view that I held at the time, and I think it is fair to say a view that quite a few people in government held at the time,” he said in a 2009 interview with the Guardian. “But … the chief scientific adviser’s view on that matter was not sought.”

He has since made it clear that he considers the Iraq war to be the first “resource war” of the 21st Century. “Future historians might look back on our particular recent past and see the Iraq war as the first of the conflicts of this kind — the first of the resource wars,” he said in a lecture the same year as the Guardian interview.

And he thought oil would not be the only target of such conflicts. In a future defined by human population growth and climate change, water and land would become increasingly more valuable and contested. “Unless we get to grips with this problem globally,” he said, “large, powerful nations will secure the resources for their own people at the expense of others.”

Access to resources has always played a part in the history of human conflict, and King’s thoughts should be seen in light of other developments — such as the rise of China as a global power, gathering resources for a burgeoning economy, and the relative decline of the United States as a global stabilizing force. With all this in mind, we take a look at the top 10 regions or countries likely to suffer resource-related conflict or already carrying the scars of such conflict in their past. Sadly, a cursory glance at this list reveals that Africa’s resource riches may be more curse than blessing, and a similar shadow hangs over the Middle East. These parts of the world have a long tradition of being the object of resource exploitation, but the list also illuminates the growing importance of the Pacific and Arctic. As readily accessible resources dwindle, previously neglected areas will take centre stage, along with new resource seekers.

Conflict will remain a constant, according to a U.S. academic who studies the geopolitics of oil. Jeff Colgan at American University in Washington identifies eight ways oil means war or near-war: (1) outright war with states using armed force to acquire oil reserves; (2) petro-aggression, as oil wealth shields aggressive leaders from domestic opposition and encourages them into risky foreign policy; (3) the spilling over of civil wars in oil-producing states into neighbouring states; (4) financing of insurgencies through oil revenues; (5) conflicts that break out, triggered by fears that one country might dominate the oil market; (6) clashes that happen over oil transit, such as shipping lanes and pipelines; (7) resentment of foreign workers in oil-producing states that help extremist groups recruit locals; and (8) oil as a source of friction in multilateral relations.

These mechanisms have been responsible for between one quarter and one half of interstate wars since 1973. No wonder the most important oil-producing region, the Middle East, remains the most volatile. We’ll look at it first.

1. Middle East:

The Middle East will likely remain the focus of energy-related security issues in the foreseeable future. That’s a central message in the most recent World Energy Outlook as published by the International Energy Agency in 2013. Consider some of its predictions as background.

First, China is about to become the largest oil-importing country and is expected to replace the U.S. as the largest oil-consuming country in 2030. The demand for oil in India will exceed Chinese demands by 2020. So the world’s two most populous states will find themselves in competition for oil.

Second, some of the largest energy producers will also become some of the leading users. Oil consumption in the Middle East will overtake consumption in the European Union by 2030. In other words, the world’s leading producers are increasingly becoming their own customers.

Third, unconventional sources of hydrocarbons (such as Canada’s oil sands) and ways of producing renewable energy are on the rise. Fourth, the U.S. is “moving steadily” towards meeting all of its energy needs from domestic resources by 2035 thanks to hydraulic fracturing (fracking) of shale oil and gas.

In short, emerging economies, particularly China, India and the Middle East, will drive the demand for global energy, while energy sources themselves will become increasingly diverse. But the International Energy Agency leaves no doubt that the Middle East will remain king of the hill in the longer term, no matter what. Yes, rising energy production in countries not belonging to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) will temporarily reduce the region’s influence. But non-OPEC production will start to fall back in the middle of the next decade and most increases in global supply will come from the Middle East.

So the world’s major powers, whether established or emerging, will continue to see the Middle East as crucial to their political and economic interests.

2. South Sudan

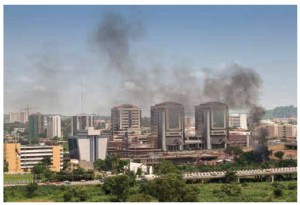

The short civil war that scorched much of South Sudan over Christmas 2013 seemed to be over in January, when forces loyal to South Sudanese President Salva Kiir captured Bor, the last major city held by forces belonging to Riek Machar, Kiir’s former vice-president. Both men struggled over control of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and their ruptured relationship escalated into an intense conflict between the country’s two largest tribes, Kiir’s Dinka and Machar’s Nuer.

Within weeks, the conflict claimed 10,000 lives and displaced close to 200,000 people as both sides vied for control of the northern cities where most of South Sudan’s oil is located. Alas, predictions of peace were premature. Western diplomats are concerned that South Sudan’s neighbours will turn the state into a battleground for their respective grievances. At the start of the conflict, neighbouring Uganda, Kenya and Sudan sided with Kiir, fearing a prolonged civil war would endanger relations with South Sudan, said to have the third-largest oil reserves in sub-Saharan Africa.

Sudan’s budget depends on transit fees South Sudan pays for shipping oil across its territory to the Red Sea and Uganda and Kenya both recently signed a deal to build an export pipeline. Machar’s rebellion represented a threat to regional economic interests, one that has inspired unusual alliances.

The most intriguing of these is Kiir’s alliance with Omar al-Bashir, president of Sudan, from which South Sudan seceded in 2011 after decades of civil war. In the 1990s, al-Bashir backed Machar as the South Sudanese feuded among themselves. Now, he may seek to develop a sustained relationship with Kiir, despite the fact that they can’t stand each other. Whether this brings peace to South Sudan is a different question. Kiir’s victory might have allowed the Dinka to re-establish their historical dominance over the Nuer and smaller ethnic groups, but it hardly addresses the larger problems that confront South Sudan. The country remains divided and possesses few, if any, viable institutions that could withstand destabilizing influences.

Which brings us to the current situation. Relations with Sudan have been historically frayed despite recent improvements and al-Bashir, who faces charges for crimes against humanity, has proven himself to be an erratic partner. Case in point, tensions between Sudan and Uganda have worsened in recent weeks. In fact, some fear their disagreements may spill over into South Sudan, an ally of Uganda. Meanwhile, Eritrea is seen as a middle-man for Sudanese weapons that end up in the hands of South Sudanese rebels, a prospect said to anger rival Ethiopia, which has served as a mediator in the South Sudanese conflict. In other words, what began as a local conflict threatens to morph into a regional one. “As far as the regionalization of the conflict goes, the question is not if, but when,” Casie Copeland, South Sudan analyst for the International Crisis Group think-tank, told the Pakistani Daily Times.

The world’s major powers also have interests. For China, South Sudan is an increasingly important oil supplier, after NATO’s intervention in Libya damaged Chinese-owned refineries there. China doesn’t want this repeated in South Sudan, where it has made significant energy investments.

South Sudan is significant for the U.S., because it played a central role in creating the world’s youngest state. Its inter-ethnic disputes threaten to undo this and turn South Sudan into another Somalia. Indeed, it was almost Black-Hawk Down revisited when the American military had to evacuate U.S. citizens from Bor; three of its aircraft faced gunfire and wounded U.S. soldiers had to be airlifted to a Kenyan hospital.

3. Niger

Rife with ethnic-religious conflicts and devoid of institutions, this fragile African state has five major ethnic groups, a Muslim majority, about 17 million people and an embarrassment of largely unexploited riches.

This combination of present dysfunction and future possibility compels competitors from every corner of the globe to seek fortune in one of the most inhospitable places on the planet. The southern Sahel is a harsh desert so hot it hurts to breathe, according to Robert Fowler, the Canadian-born diplomat held hostage several months by Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) during his time as a UN envoy in Niger.

This former French colony first made global headlines in 2003 when then-U.S. President George W. Bush announced that the British government “has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” Later reporting revealed this falsehood relied on forged intelligence reports that claimed Iraq had tried to purchase yellowcake — enriched uranium — from Niger, the world’s fifth largest producer of that mineral. Ten years later, the country’s uranium reserves are contributing to a conflict with ramifications far beyond its borders.

Niger plays a pivotal part in the energy portfolio of its former colonial master, France, and, by extension, the European Union. Up to 76 percent of France’s energy comes from nuclear power and almost 40 percent of the uranium it needs comes from Niger, according to Stratfor Global Intelligence. The French government has a direct role in the affairs of Niger through Areva, its state-owned nuclear power company, which operates two mines in Niger that produce roughly seven percent of global uranium output.

So France possesses an immense strategic interest in Niger and its immediate neighbours, including Mali, where French troops have been trying to stabilize a weak pro-Western government since their arrival (Operation Serval) more than a year ago. President François Hollande has framed this intervention as a counter-insurgency against Islamists threatening to destabilize the southern flank of the Sahara from Senegal to Chad. Security wonks increasingly call this region “Sahelistan,” an allusion to the tribal regions bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan. Critics see Hollande’s move as part of a neo-colonial agenda to protect the French economy. This critique gained more currency in February 2013 when France deployed soldiers to protect an Areva mine near Arlit to prevent an attack similar to the one that had killed 37 employees when Islamist militants seized a gas plant in neighbouring Algeria.

Several weeks later, an Islamist suicide attack against this very uranium mine killed one Areva employee and injured 15 others. The environmental fallout from Areva’s mining has further stoked local resentment against France and its allies in Niger’s government.

But if Niger remains beholden to France for its political and economic security, it also finds itself in the middle between China and the United States. The former seeks to exploit Niger’s oil reserves, while the latter sees Niger as an important front in its anti-terrorism efforts. Agendas are bound to clash.

4. South China Sea

It will likely take several years before China’s first aircraft carrier will be in full service, because the Liaoning still lacks operational fighter jets. Yet this floating symbol of China’s emerging global ambition was the focus of an incident that symbolized the China-U.S. struggle for supremacy in the South China Sea.

On Dec. 5, 2013 a small Chinese warship escorting the Liaoning nearly clashed with the USS Cowpens in international waters. While accounts vary — Chinese officials claim the American guided-missile cruiser harassed their aircraft carrier — it was the most serious incident since 2009, when five Chinese naval ships surrounded the American surveillance ship USNS Impeccable patrolling in an area that China claims as an “exclusive economic zone.”

Incidents such as this are the most likely to provoke an armed Chinese response, according to the Council on Foreign Relations. It deems the risk of conflict in the region as “significant” for two reasons. The first is resources. China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines have competing jurisdictional claims over the right to exploit the region’s potentially extensive reserves of oil and gas. The second issue is freedom of navigation, the question of whether U.S. military vessels can freely operate in exclusive economic zones. The U.S. says yes it can, citing common practice and the absence of rules in the UN Conventions on the Law of the Sea. China, however, insists reconnaissance without prior notification and permission violates domestic and international law. So in the last few years there has been a high-stakes game of cat and mouse as both sides test the resolve of the other.

These tensions shape, and are subsequently shaped by the “rising apprehensions about the growth of China’s military power and its regional intentions,” as the Council on Foreign Relations notes. Such fears are bound to increase as China and its neighbours compete for access to the area.

An emerging flashpoint are the Senkaku (also known as Diaoyu) islands in the nearby East China Sea. While Japan, Taiwan and China claim these islands, China recently expanded its Air Defence Identification Zone to include them. Its rules specify that all aircraft entering the region must notify Chinese authorities and are subject to emergency military measures if they don’t.

The U.S. immediately tested this claim by flying two B-52s through the zone without notice. A day later, the Liaoning set sail for the South China Sea and its close encounter with the USS Cowpens. Expect this sort of brinkmanship to intensify, especially in light of U.S. defence agreements with nearby countries, including Japan and the Philippines.

5. The Arctic

Almost a decade has passed since a Russian mini-submarine planted its country’s flag on the seabed at the North Pole. Was it the opening salvo in a scramble for the riches of the Arctic, or just a stunt by Russian President Vladimir Putin to promote his corrupt, territorial regime? Opinions differ, to say the least.

If we believe Michael T. Klare, who has written extensively on this subject, the incident was part of the race for a shrinking supply of natural resources, a race he predicts will stoke worldwide rivalries and leave behind devastating environmental, economic and political consequences. This “race for what’s left” is bound to be intense in the Arctic, where “some of the world’s largest untapped reserves of oil and natural gas” are waiting to be found.

Writing in Foreign Affairs, Scott G. Borgerson agrees with the larger narrative that accelerating climate change will open a treasure trove of resources, including massive deposits of valuable minerals and nearly a quarter of the world’s estimated undiscovered oil and gas. This “Arctic boom,” Borgerson says, will involve more than just mining and drilling. It will also improve access to wood, water and a wide variety of commercial activities, including increased air and ship traffic, as melting ice turns “once-fabled shipping shortcuts” like the Northwest Passage into reality.

But unlike Klare, Borgerson believes the economic potential of the region will encourage co-operation, not competition, because a “shared interest in profit has trumped the instinct to compete over territory.”

Arctic countries, he argues, have begun “making remarkably concerted efforts to co-operate rather than fight, as the region opens up, settling old boundary disputes peacefully and letting international law guide their behaviour.” And, he notes, the Arctic possesses at least two conditions to dampen future conflict. Most countries with territory above the Arctic Circle have the money for the infrastructure necessary to exploit the region, but also protect it. Most of them (minus Russia) have well-functioning legal systems and clear regulations favoured by foreign investors. “Thanks to good governance and good geography, such cities as Anchorage and Reykjavik could someday become major shipping centres and financial capitals — the high latitude equivalents of Singapore and Dubai,” Borgerson writes.

But Borgerson understates the difficulties that lie ahead. The region is difficult to reach, under-populated and under-resourced. This hampers any response to emergencies, environmental or otherwise. Issues such as the status of the Northwest Passage — Canada claims it as an internal waterway, the U.S. insists it be international — remain unresolved.

Finally, the number of would-be actors in the region is not limited to countries with Arctic shorelines. In addition to its eight full-time voting members, the Arctic Council also includes 12 non-voting observers, including China, which has expended much effort to gain a foothold in the region and is pushing for a greater role on the council, something not everyone likes.

6. Nigeria

These days, Africa’s most populous, and arguably most important, nation rarely appears in western media accounts unless they involve Boko Haram, the Islamist group that has claimed to establish a Sharia-conforming state in northern Nigeria. These stories are often formulaic, neatly conforming to the narratives that sprang to life after the events of 9/11 — Christians versus Muslims, modernity versus religious intolerance, good versus evil.

It’s true that Boko Haram’s actions are indefensible and its agenda reprehensible. But a closer look also reveals that it is only the most recent threat in a tapestry of corruption and violence that has pervaded Nigeria since the late 1950s, when multi-national companies began to exploit the oil in the Niger Delta. The group’s narrative relies on the notion that Nigeria’s Christian south has disproportionately monopolized the country’s leadership and profited from its oil at the expense of the north.

In fact, neither north nor south has benefited from the oil. Despite being one of the largest oil producers in the world, Nigeria finds itself towards the bottom of the UN Development Index, thanks to a corrupt elite whose allegiances transcend religious and regional loyalties. This helps explain the appeal of Boko Haram’s message, which blames western modernity for all that ails northern Nigeria. This message might be simplistic and misleading, but is a variation on the larger point that economic inequality leads to violence. It’s a rerun of the mid-to-late 2000s, when the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta waged an insurgency against the Nigerian government and western oil companies held responsible for the social inequality and environmental devastation that defines the Niger Delta.

In short, Boko Haram is neither the first, nor the last, armed militia to challenge the Nigerian state at considerable cost in blood, property and stability throughout the region.

7. Democratic Republic of Congo

Two sorts of people live in the Democratic Republic of Congo — those who try to exploit its resources and those who suffer at their hands. This sociology has defined Africa’s second-largest and fourth most populous state since the days of 19th Century European colonialism when Belgium’s King Leopold II declared the country his “private property.”

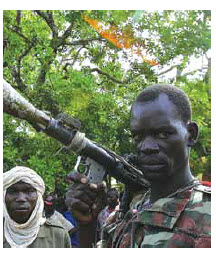

Belgian colonial rule ended in chaos decades ago, but exploitation of the Congo continued through the immediate post-colonial period, the Cold War and the ethnic wars that then erupted across Africa. The current gang of plunderers has a multi-national flavour: corrupt local politicians, ruthless warlords from inside and outside the country and a shadowy network of global financiers who sustain these groups while siphoning the country’s wealth into their own pockets. To appreciate this form of contemporary capitalism, consider Congo’s role in the trade of coltan, a rare ore used in electronics and other industrial goods. Up to 80 percent of global coltan reserves lie in the Congo, yet officially the country plays no major role in its global markets. Most of Congo’s coltan leaves the country through unofficial channels as competing warlords operate ad hoc mines, where workers, many of them prisoners captured from rival militias, slave away under dangerous conditions, often with nothing more than their bare hands.

The mineral then finds its way onto international markets through a network of dubious dealers, many based in Belgium. Yes, would-be users of coltan are aware of this system, but its opaqueness makes it difficult to know where their purchases come from. This system has perpetuated the violence that has gripped Congo since the mid-1990s and cost millions of people their lives, because it flushes money into the hands of competing warlords who use it to equip and pay their troops.

The DRC also suffers from other pathologies — unresolved ethnic tensions, non-existent institutions — that plague most African nations. It’s no surprise to learn that the coltan reserves are in the contested Kivu region where Congo borders its much smaller neighbours, Uganda and Rwanda, both of which have sought coltan profits through sponsoring rebel groups opposed to the DRC’s government. The UN is trying to stabilize this region through one of the largest, most expensive and most robust interventions in its history, with some success. But the DRC will likely remain a deadly El Dorado for greedy privateers.

8.The Caspian Sea Basin and Central Asia

The 19th Century witnessed what historians call the Great Game, the political struggle between Czarist Russia and the United Kingdom for strategic supremacy in Central Asia, as Russia tried to reach the Indian Ocean in challenging British control of the Indian subcontinent.

We may well see a New Great Game, this time revolving around the oil and natural gas in the same region. While these reserves across Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are likely not as extensive as the Middle East’s, they have attracted all the major energy-consuming nations.

The region also includes Iran and Russia, even though neither requires such resources because each is rich in its own right. But each pursues strategic interests there, especially Russia, which considers the area its “Near Abroad,” the term used to describe the former Soviet republics ringing its borders. Russia has been particularly keen to maintain control of the pipelines that carry energy from the landlocked Caspian Sea Basin to foreign markets.

Geography has made the Caspian Sea Basin attractive to Chinese interests because that country’s relative proximity means it can import oil and natural gas through pipelines. This calms Chinese anxiety about losing access to the Middle East, because it can’t defend oil shipments across seas against the strength of the U.S. navy.

This said, the pipelines that cross the region are not exactly traversing realms of peace and prosperity: Russia and Georgia remain at odds over the status of South Ossetia and Abkhazia following a five-day war in 2008; Islamist separatists have embroiled Russia in Chechnya; Armenia and Azerbaijan dispute the status of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave located inside Azerbaijan. The region beyond the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea is just as rife with potential flashpoints among simmering ethnic tensions, corruption and repression in the Central Asian republics. Beyond that, the agony of Afghanistan could easily spill across borders to the east and south, namely China and Pakistan.

9. Central African Republic

How do you spell “quagmire” in French? The Economist asked this about France’s most recent military involvement in its former colony. In late 2013, Paris deployed 1,600 troops to the landlocked country as part of a UN mission to end sectarian violence that had started when Muslim Seleka rebels embarked on a reign of terror that raised the spectre of the Rwandan genocide. It’s still uncertain whether France’s involvement has stabilized the country, which borders six neighbours, including Chad, whose government has been accused of siding with the rebels. Christian militias have retaliated against the country’s minority Muslims, who make up about 10 percent of the population. This violence has cost countless lives, displaced thousands of people and brought further misery to one of the worst-governed states in Africa.

There are multiple reasons for the bloodshed, but many would insist that it has little to do with religion. Before recent events, Muslims and Christians had long co-existed in peace. Observers would instead point to a battle for control over the country’s natural resources. While rich in diamonds, timber, gold, uranium and oil, the Central African Republic remains among the poorest African nations, thanks to decades of political turmoil and corruption.

As Reuters news agency noted, the Seleka rebels launched their uprising to get at resource wealth, especially the oil being exploited by the China Petroleum Corporation. These efforts failed, but the failure hardly means the end of instability, no matter how long France chooses to remain the region’s gendarme.

10. Ivory Coast

Prime Minister Daniel Kablan Duncan could not have been clearer when he addressed a group of potential international investors last December. “We are really open to all the world,” he said. “We are now normal … and we want the rest of the world here.”

Duncan’s message was intended to assure his listeners that the government of his West African country was legitimate and stable after more than a decade of conflict, and to convince them that Ivory Coast offers untapped business opportunities, especially in gold mining. The country lies along the Birimian Greenstone Belt, a rock formation two billion years old and stretching from Senegal to Ghana. According to the Guardian, it contains some of the richest gold deposits in the world. So Ivory Coast might overtake its neighbour, Ghana, to become Africa’s second-largest producer of the precious metal after South Africa.

Mining would diversify the country’s economy, which for decades has relied on the sparser returns from cocoa, coffee and cashew exports. But the gold rush is impending while the country is still seeking a solution to the problem that caused the preceding violence in the first place: ethnic disputes over farmland.

This issue occurs against a backdrop of the global rush for arable land. Private companies and governments from China, India, Saudi Arabia, Europe and the U.S. lease and buy land in the developing world to grow food, biofuel and cash crops. Critics have decried this land grab as neo-colonialism and warned it threatens global food security in the face of climate change and warned also that it could trigger social unrest as foreign corporations ignore the locals. Ivory Coast has offered a historical precedent for what could happen if businesses or governments compete over non-renewable resources.

Wolfgang Depner is a doctoral candidate at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan and the co-editor of Readings in Political Idealogies since the Rise of Modern Science, published by Oxford University Press.