Meline Toumani is a young Iranian-born Armenian who grew up in New Jersey and began her writing career as an editorial assistant at the New York Times. So it was one day that she was in Times Square, a block from the office, when she saw the annual street protest of Turkish people with signs reading “Armenians Are Killers of Children” and “Armenians! You’re Guilty of Genocide!” Continuing on a very short distance, she ran into Armenian demonstrators with placards that said “Turkey Guilty of Genocide.” In her book, There Was and There Was Not: A Journey through Hate and Possibility in Turkey, Armenia, and Beyond (Raincoast, $32.50), she writes: “That day I stood among the Turks. I wanted to see how it would feel.”

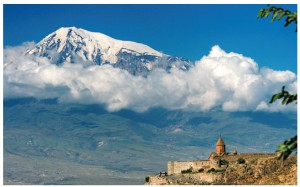

Like the majority of Armenians, both the diaspora and those living in the country, she was educated to believe that the Muslims who ruled the Ottoman Empire a century ago murdered so many Armenian Christians as to almost exterminate that part of the population in certain areas (today there still 50,000 Armenians in Istanbul). Her brave, revealing and moving book is the story of one who was brought up to share that belief — indeed, had it pounded into her brain — but has slowly found closure of sorts by trying her best to learn about the other side. The process began in 2005 when, age 30, she went to Turkey, a place about which she confesses to knowing less “at that point than the average backpacker [but having] a strong urge to seem like I belonged.” She spent most of the next four years in Istanbul (which many Armenians called Bolis).

What Armenians know as the great genocide, but Turks interpret in terms that are less stark, began in the early spring of 1915. Since the start of the Great War the previous August, the Ottomans had been aligned with Germany, fighting against the British Empire (Gallipoli, remember — and Lawrence of Arabia). Militarily they were not doing well and came to believe that the Armenians among them were undermining the war effort and even supporting Russia, which fought with the West until Lenin came to power and pulled his country out of the conflict altogether.

What Armenians know as the great genocide, but Turks interpret in terms that are less stark, began in the early spring of 1915. Since the start of the Great War the previous August, the Ottomans had been aligned with Germany, fighting against the British Empire (Gallipoli, remember — and Lawrence of Arabia). Militarily they were not doing well and came to believe that the Armenians among them were undermining the war effort and even supporting Russia, which fought with the West until Lenin came to power and pulled his country out of the conflict altogether.

On April 24 (the date is now the Armenian day of national protest) more than 200 Armenian intellectuals, politicians and community leaders in Istanbul (then still called Constantinople) — some of them already refugees — were arrested by Turkish paramilitary forces and sent to the Anatolian countryside. This was followed by large-scale deportations, forced marches, abuse, torture and, of course, death on a horrific scale that went on for several years. Armenians put the total number of their dead at 1.5 million; the Turks, a smaller figure. Armenians interpret the events as what we would now call ethnic cleansing. The Turks called the dead casualties of a civil war and spoke of the Armenian point of view as “Allied propaganda.”

Ms Toumani terms what took place on April 24 “a kind of Kristallnacht in the way it foretold the years of deportation and massacre that would follow.” Some commentators less careful than her compare the anti-Armenian actions to the Holocaust, citing what Hitler said when asked how history might view the extermination of Jews (“Who today remembers the extermination of the Armenians?”). But it proves nothing to say that four or five times as many people perished in the Holocaust than in the Ottoman horrors or that far fewer Chinese, maybe 600,000, were killed by the Japanese in 1937 during what’s called the Rape of Nanking. Comparative totals are less important to remember than the intent and the unspeakable immorality of such events.

“I had been reading tragic memoirs and gruesome eyewitness accounts from the genocide survivors since I was old enough to read Dr. Seuss,” the author writes. Elsewhere, she says she “could no longer live with the idea that I was supposed to hate, fear and fight against an entire nation and people […] Do I sound like I’m exaggerating? Is there such a thing as nationalism that is not exaggerated?” The heart of her argument is that Armenians continue to fixate on long-ago events rather than simply memorialize them sadly. Armenians use the word recognition to explain their goal: universal acknowledgement of the genocide and, in some people’s view, reparations as well. To these ends, they continue an unceasingly strenuous lobbying effort. To date, for example, 43 American states have officially acknowledged the Armenian point of view, but the federal government has not.

For a time, Ms Toumani believed that such efforts contributed to the slow economic development of her ancestral homeland (just as Turkey’s recalcitrance has hindered its wish to join the European Union). She concedes, however, that her “argument about the effect of the diaspora’s genocide recognition campaigns on Armenia’s economy was probably flawed, or at the very least incomplete. But it was as close as I could come to finding an argument that would justify a feeling that I didn’t know how else to defend: that our obsession with 1915 was destroying us.”

Istanbul, mon amour

As Ms Toumani’s book draws to a close, she writes this of Istanbul, a gateway to both Europe and Asia: “Yes, it was East and West; yes, it was a bridge between worlds; yes, it was oriental and exotic while still being modern and glamorous. All the clichés were spot-on. For me, it was all these things, too, but it was ultimately a place where this single dimension of my life, my being Armenian — this feeling of fatigue with the clannishness and conformity of Armenian life — I had come to Turkey hoping to escape, or at least to broaden — had become more a fact of my existence than it had ever been before.”

That is to say that, while probably remaining ambivalent about Turkey as a whole — the pivotal state where, who knows, the future of the Middle East could very well be decided — she nonetheless has fallen under the spell of Istanbul, and who doesn’t? Well, another who certainly has done so is Charles King of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., whose book, Midnight at Pera Palace: The Birth of Modern Istanbul (Penguin Canada, $32.95), is an exciting study of how Constantinople became, under its new name, the capital of the Turkish republic. This change came about in 1923 once what the author calls “the most over-anticipated event in diplomatic history” — the Ottoman collapse — finally came to pass. He goes on: “Arguing over how other countries and empires might profit from its end was one of the fixtures of great-power diplomacy for much of the 19th Century.”

The outcome was that Britain and France took over large sections of the city for themselves, with special courts for their citizens and so on. These actions can be seen as a continuation of the events immediately after the Great War when the same two Western powers created the state of Iraq, drawing up boundaries that are only now starting to be erased and replaced. From today’s standpoint, it’s difficult to imagine how widely, and how recently, the Middle East was hospitable to westerners. For example, a late friend of mine, a poet, passed the late 1960s in Iran, writing a nightclub column called “Tehran after Dark” in the local English-language newspaper. But Istanbul was different in the extent of its cosmopolitanism and the width of his wide open arms. Only in Shanghai before the Second World War, and possibly Tangier afterwards, did foreign communities have such personal freedom and such a good time. But then Istanbul had always inclined that way.

As Mr. King states admiringly, “A Greek shipper, a Jewish cloth merchant, an Arab pearl diver, a Kurdish caravan master and an Armenian financier could all regard themselves as subjects of a single sovereign, the Ottoman sultan.” The Pera Palace of his book’s title was (and is) a famously posh hotel that, when built in 1892, “was meant to be the last whisper of the Occident on the way to the Orient, the grandest Western-style hotel in the seat of the world’s greatest Islamic empire.” Once the Turks, “in one of modern history’s most profound exercises in political self-creation, made a purposeful break with their Ottoman past, rejecting an Islamic and multi-religious empire and declaring in its place a secular, more homogeneous republic” — the Istanbul known to readers of such novelists as Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and Ian Fleming — the sophistication remained, though it was tinged with nationalism. Which brings us back to the Armenian question.

Being himself neither Turkish nor Armenian, Mr. King takes a broader view of the events leading up to the genocide. In the last few years of world peace before the Great War, military officers known variously as Young Turks or Unionists organized a coup to create a constitutional monarchy and then had to fend off a counter-coup. When the big war finally broke out, they blamed, in addition to the sultan, those whom they believed were sympathetic to Germany and those who sided with it.

This meant Armenians primarily, some of whom had been running revolutionary groups for years. They “operated openly in Istanbul and, in 1896, had staged a spectacular raid on the Imperial Ottoman Bank, just down the hill from the Grande Rue.” In eastern Anatolia, military units and militias organized the roundup and deportation of entire villages of Armenians and other Eastern Christians who were thought to be potentially loyal to Russia.” Armenian groups “had in fact organized uprisings in Armenian areas of the empire” and the Unionists “responded with a campaign of death.” One of the important Unionist leaders, a civilian called Talât Pasha, fled the country on a German submarine. Three years later, an Armenian assassin killed him in Berlin as payback for his role in the genocide, which, in Mr. King’s broad estimate, took the lives of between 600,000 and one million men, women and children.

A footnote to the above: There has been a sudden surge of interest in the architecture, costumes and minor arts of the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman Chic by Serdar Guigun (Assouline, $47.50) is one example. The almost equally lavish Turquerie by Haydn Williams (Penguin Canada, $46.50) is another.

Peaceful converts to Islam

One can scarcely read the newspapers today without finding references to Europeans, and North Americans, too, who have gone to the Middle East and embraced Islam. Jamie Gilham’s book Loyal Enemies: British Converts to Islam 1850–1950 (Oxford University Press, $20) deals with many others who did the same, but with peaceful intent. Of course, there were a great many Britons who settled in the region without leaving much of a historical footprint: for example, seamen and others who adopted Islam after being captured by Islamic enemies. Mr. Gilham, a journalist who is also a publisher of travel books about the Middle East, has ferreted out whatever information about such unfortunates as can be found, but goes into far greater detail on prominent personages who also became Muslims: scholars, politicians, and so on.

The third Baron Stanley (1827–1903), no relation to Lord Stanley of the Stanley Cup, converted in 1862. He became the first Muslim to sit in the House of Lords (and as such closed down all the public houses on the vast lands he had inherited). William (later Abdullah) Quilliam (1856–1932) was a Liverpool lawyer who opened England’s first mosque and Islamic centre. Lady Evelyn Cobbold (1876–1963), a Mayfair socialite, was the first British woman to undertake the Hajj to Mecca. She was a friend not only of T.E. Lawrence, but also of Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall (1875–1936), who made a famous English translation of the Koran, and of St. John (pronounced Sinjin) Philby, the great Arabist scholar who was also a British spy. Pickthall served in the Great War on the stipulation that he would not have to fight any Turks. As for Philby, he was the father of Kim Philby, the British spy who turned out to be a double agent and fled to the Soviet Union, where he died. Mr. Gilham shows that all these people were shunned and at least looked down upon in Britain for their Islamic beliefs.

The third Baron Stanley (1827–1903), no relation to Lord Stanley of the Stanley Cup, converted in 1862. He became the first Muslim to sit in the House of Lords (and as such closed down all the public houses on the vast lands he had inherited). William (later Abdullah) Quilliam (1856–1932) was a Liverpool lawyer who opened England’s first mosque and Islamic centre. Lady Evelyn Cobbold (1876–1963), a Mayfair socialite, was the first British woman to undertake the Hajj to Mecca. She was a friend not only of T.E. Lawrence, but also of Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall (1875–1936), who made a famous English translation of the Koran, and of St. John (pronounced Sinjin) Philby, the great Arabist scholar who was also a British spy. Pickthall served in the Great War on the stipulation that he would not have to fight any Turks. As for Philby, he was the father of Kim Philby, the British spy who turned out to be a double agent and fled to the Soviet Union, where he died. Mr. Gilham shows that all these people were shunned and at least looked down upon in Britain for their Islamic beliefs.

Eastward by rail

In Midnight at the Pera Palace, discussed previously, Charles King tells of how the Orient Express, the famous luxury railway train of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et des Grands-Express Européens, finally reached Istanbul in 1883. He writes that until the firm was established, in 1876, people had never “imagined that a single rail company could operate lines running across the entire [European] continent.” Metaphorically at least, it may have given those building the Canadian Pacific a morale boost. Nowadays, China has the world’s longest and fastest rail lines, which it intends to extend beyond Asia. But that still leaves the Trans-Siberian railway across Russia. It “is not some little meandering rural railway with occasional chundering trains, but rather, one of the world’s great arteries, a piece of infrastructure that transformed not only the region in which it was built, but also the entire nation that built it.”

So writes Christian Wolmar in To the Edge of the World: The Story of The Trans-Siberian Express, The World’s Greatest Railroad (Publishers Group Canada, $31). Actually the Trans-Sib is a tangle of different lines, including one that runs through Mongolia to the Chinese capital, though the most famous route is the first, completed in 1916 and stretching from Moscow to Vladivostok, a distance of 9,288 kilometres. Mr. Wolmar, a full-time railway historian (his previous book was a history of the London Underground), tells of the lines’ military, political and diplomatic history as he travels along as passenger, happily for the most part. My own experience was somewhat different. More than 25 years ago, I was in Moscow watching the Soviet Union collapse when my editor expressed a wish for me to be in Beijing instead. I spent nine days on a train containing four days’ worth of food.

So writes Christian Wolmar in To the Edge of the World: The Story of The Trans-Siberian Express, The World’s Greatest Railroad (Publishers Group Canada, $31). Actually the Trans-Sib is a tangle of different lines, including one that runs through Mongolia to the Chinese capital, though the most famous route is the first, completed in 1916 and stretching from Moscow to Vladivostok, a distance of 9,288 kilometres. Mr. Wolmar, a full-time railway historian (his previous book was a history of the London Underground), tells of the lines’ military, political and diplomatic history as he travels along as passenger, happily for the most part. My own experience was somewhat different. More than 25 years ago, I was in Moscow watching the Soviet Union collapse when my editor expressed a wish for me to be in Beijing instead. I spent nine days on a train containing four days’ worth of food.

And lastly…

New books about John F. Kennedy never stop appearing — ever. Some of those with the most interesting perspectives aren’t always the best executed. For example, Dallas 1963 by Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis (Hachette Canada, $31) goes beneath the president’s assassination to reveal the level of political hatred in the city that was the scene of the crime. Unfortunately, it’s written much too casually and takes a plodding minute-by-minute approach to narrative. If you want to see how such a tactic can be used expertly, read Two Days in June (McClelland & Stewart, $34) by Andrew Cohen, whose transition from the Globe and Mail to Carleton University was the newspaper’s loss and the school’s gain. He reconstructs a 48-hour period in June 1963 when Kennedy gave two of his most meaningful, if not necessarily his most famous, addresses — the first on nuclear disarmament (“We are all mortal…”), the other on civil rights (challenging his audience to investigate the content of their own hearts). This is excellent historical writing in the manner of Barbara Tuchman and Margaret MacMillan.

George Fetherling is a novelist and

cultural commentator.