Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s graceful acceptance of his loss this year to incoming President Muhammadu Buhari was a major advance for African democracy, for setting peaceful transition precedents, and for helping to mature political leadership on the continent. But that easy handover to an opponent was exceptional. Equally often, African rulers cling tenaciously to their hard-won positions, attempt to evade or thwart popular mandates and violate constitutional bans against perpetual presidencies. Democracy still battles autocracy across Africa.

Although 20 of sub-Saharan Africa’s 49 nations limit their heads of state to two terms, two states permit three terms, and three put prime ministers rather than presidents in charge. Many of the continent’s political chiefs are still trying to replicate the “president-for-life” model that was such a feature of earlier years. They endorse their own indispensability and seek to continue to retain the spoils of office indefinitely. Credible surveys show that citizens prefer constitutionality, but several of the “big men,” Africa’s legacy rulers, persist in employing the mailed fist to stay ascendant.

What this means, of course, is that democratic practices are, as yet, not fully accepted by Africa’s political class. Respect for constitutions is still not a mature norm. Nevertheless, widespread civil society opposition to such manoeuvers, parliamentary refusals in several cases to abridge constitutional bans and a number of effective transitions from president to president demonstrate that at least a large swath of Africa is ready to obey the rule of law. One president, Macky Sall of Senegal, is even proposing to reduce presidential terms from seven to five years.

Heavy-handed repression

Pierre Nkurunziza’s “re-election” in July for a third five-year term as president of Burundi violated the terms of his country’s constitution, defied African Union condemnations, ignored pleas of world leaders and reneged on the promises that he had repeatedly made over the past decade. His re-anointment also frustrated the fervent protesters who, for months, had roiled the political waters of Bujumbura, Burundi’s capital on Lake Tanganyika, and other towns and villages in the small Central African nation. Heavy-handed repression by soldiers and police officers had checked the opponents in the streets and had imprisoned 500 reporters, broadcasters and civil society leaders who had been fighting to maintain term limits. A vice-president and other prominent former supporters fled to neighbouring Rwanda. About 200,000 Burundians followed them across the border, and also into neighbouring Tanzania. Nkurunziza said that he was “in touch with God, and does God’s wishes.”

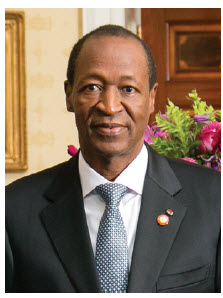

Since 2000, a dozen “big men” have attempted to circumvent the standard two-term limit for heads of state that is embedded in many African constitutions. Half have failed, most notoriously and surprisingly, President Blaise Compaoré in Burkina Faso in 2014. After a successful coup in 1987 and 27 consecutive years as the uncontested leader of his West African country, Compaoré’s attempt to seek a third term as president (he had been elected president in 2005 and 2010) was thwarted when the citizens of Ouagadougou, Burkina’s expanding capital, rose up in their thousands for four days to decry Compaoré’s anti-democratic manoeuvers. He fled, and young military officers took over, promising elections in October and respect for the constitution.

Compaoré’s exit was more dramatic than most. But before he failed to breach the third-term prohibition, Bakili Muluzi in Malawi, Sam Nujoma in Namibia, Olusegun Obasanjo in Nigeria, Frederick Chiluba in Zambia, Mamadou Tandja in Niger and Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal had all been prevented by civil society agitation and parliamentary reluctance from pursuing their third-term dreams. In each case, the attempt to overturn constitutional bans was unpopular, believed to be unnecessarily narcissistic and judged offensive to prevailing norms.

A further dozen African presidents have all quietly left office in recent years after completing two terms. Whether or not they believed themselves “big men” in the African political manner, they decided (in a few cases very reluctantly) not even to contemplate trying to overturn constitutional limitations. Their actions reflected respect for the rule of law.

African “big men”

But not so Nkurunziza, who tossed aside those profiles in presidential probity. Equally, what happened to the losing sextet of third-term wannabes (Muluzi and the rest) and Compaoré might conceivably have cautioned Nkurunziza and stilled his disdain for Burundi’s constitution, popular and world opinion and democratic norms. But, either more resolute or more sure of his own security forces (which negated a coup attempt in June), Nkurunziza survived, thus emboldening those other African “big men” who also seem anxious in 2015 to override third-term constitutional prohibitions.

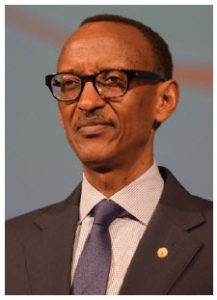

Foremost is President Paul Kagame in Rwanda, now approaching the end of his second seven-year term as omnipotent ruler. Kagame and his insurgent troops rescued Rwanda from its horrific genocide in 1994, marching into the country from neighbouring Uganda. He remained as minister of defence and the power behind a president he selected until 2000, when he himself took unquestioned control. Under a new constitution, he was elected president in 2003 and again in 2010 with 93 percent of the vote. Now Kagame, who says he is “open to going or not going depending on the interest and future of this country,” is orchestrating a “popular” movement to demand that the constitution be amended so he can continue in office beyond 2017, when his current term ends.

Kagame, 57, has, in recent years, physically eliminated, imprisoned or exiled key critics and opponents. Lawyers are chary of appearing in court to plead against a third term. There is little free media or free expression, many arbitrary arrests, reported cases of torture and several documented assassinations. But Kagame also runs a crime-free, stable and rapidly developing country. Most Rwandans, if permitted to vote freely, would probably choose to keep the Kagame they know. Nevertheless, democracy in Africa will suffer considerably if one of the continent’s sharpest and most successful political leaders succumbs to third-termitis and decides to monopolize Rwanda’s presidency. Unless effective leaders such as Kagame set positive examples, respect for the rule of law and constitutionalism will continue to be honoured only now and then, when convenient. Stepping down is the ultimate act of responsible leadership.

Perpetuating corrupt reigns

Joining Kagame as likely breakers of third-term rules will be President Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), already in power for 18 years, and previously for a further 13, and his across-the-river neighbour Joseph Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Kinshasa), in command for 14 years. The constitutions of both Congos ban third terms, but Kabila, who is only 41, and Sassou Nguesso, 71, both want to continue to preside. They seek to perpetuate reigns that are corrupt, Kabila’s excessively so, and which have permitted the spoils of office from petroleum and mineral exports to flow copiously into elite pockets while most Congolese remain poor and mired in conflict. Despite American and European private and public entreaties to both men to refrain from pursuing third-term options, there is every likelihood that Sassou Nguesso and Kabila will join Kagame in attempting to break the law and prove themselves inviolable.

If Kagame and the others persist in believing in their personal indispensability, they will join those several additional African heads of state, most much more despotic, who in 2015 hold power by virtue of rigged elections, military intimidation or both. President Robert G. Mugabe has run Zimbabwe since 1980 thanks to fake polls throughout this decade, a successful security apparatus, major intimidation efforts and the acquiescence of neighbouring South Africa. Paul Biya, 82, has remained president of Cameroon since 1982 because of similar refusals to permit fair electoral contests or significant opposition. In 1996, he ignored Cameroon’s two-term limits and stayed in office. In 2008, he eliminated term limits from its constitution. Cameroon’s next presidential “election” is in 2018. Yoweri K. Museveni, 70, has been president of Uganda since 1986, overcoming term limit constraints in 2005. He arrested two leading opposition presidential candidates in mid-2015. Museveni is the man who originally declared that “the problem of Africa… is not the people, but leaders who want to overstay in power.”

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, 73, has been president of oil-rich Equatorial Guinea since 1979. His rule is arbitrary and kleptocratic, as is the reign in equally wealthy petroleum-dependent Angola of Eduardo dos Santos, 72, also president since 1979. Both head countries where corrupt practices run free, thanks to Chinese purchases of oil.

Chad’s Idriss Déby, 63, president since 1990, has defeated Libyan and Sudanese attempts to oust him; his army is one of the best-trained and best-equipped in Africa. It keeps him in office and helped to ensure his unconstitutional third term in 2005. In tiny Djibouti, on the Red Sea, Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, 67, backed by a small army financed by France (which, along with the United States, has a strategic base there) overcame third-term prohibitions in 2010. He has been president since 1999, succeeding his uncle.

Fleeing Eritreans trying to reach Europe

President Yahya Jammeh, 50, of Gambia, a tiny West African sliver of a state, has been a wildly impulsive, cruel military ruler since taking power in a 1994 coup and getting himself elected head of state in 1996. Isaias Afwerki, 69, in Eritrea on the Red Sea, came to power as an anti-Communist revolutionary in 1993 and has relentlessly extirpated all opposition ever since. He also conscripts anyone he can find, especially children, into his rag-tag army, has jailed or killed a dozen journalists, and has bad relations with the rest of Africa. Thousands of the migrants trying to cross today from Libya into Europe are fleeing conditions in Eritrea.

Bringing respect for democratic procedures to all of these benighted nations will not be easy. Mugabe is 91, and still rules with a consummately strong hand. His handpicked successor is less popular, but backed by the security forces. Biya also is apt to remain in office until natural causes remove him. Afwerki and Jammeh, and even Mugabe, Biya, dos Santos and Nguema could easily be overthrown if the militaries in those places were so-minded and if those four capricious strong men lost their canny ability to provide patronage to politicians and looting opportunities to soldiers. Civil society in all six places is weak.

These despots are outliers, especially when contrasted to the African Union members such as Botswana, Tanzania and Senegal that have adhered rigorously to constitutional prerogatives and prescriptions, and prospered. If Kagame, Kabila and the others prone to the third-term malady can be persuaded to renounce such pretensions, and instead begin to burnish their democratic credentials, Africa’s future will brighten considerably.

Robert I. Rotberg is fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center; senior fellow, Centre for International Governance Innovation; fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences; president emeritus, World Peace Foundation, and founding director of Harvard’s Kennedy School program on intrastate conflict.