The boundary between Canada and the United States was a matter of dispute between 1783 and 1872, when the issue was arbitrated by German Emperor Wilhelm I. The last portion of the boundary had been ambiguously determined by the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which extended the 49th parallel “to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island, and thence southerly through the middle of said channel, and of Fuca’s Straits, to the Pacific Ocean.”

However, the “middle of the channel” could have applied either to Rosario Strait, to the east of San Juan, Orcas and Lopez islands, or to Haro Strait, to the west of the islands. San Juan Island, which was claimed by both Britain and the U.S., was a strategic military position; the country that owned the islands would dominate the waterways connecting the Strait of Juan de Fuca with the Strait of Georgia.

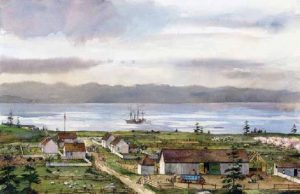

The Hudson’s Bay Company had claimed San Juan Island in 1845 and established salmon curing stations along the western shoreline by 1851. In 1853, the U.S. claimed the three islands as part of the new Washington Territory. In response, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Bellevue Sheep Farm in December 1853. In only six years, it grew from 1,369 sheep to more than 4,500 on stations across the island. A boundary commission established in 1856 failed to resolve the issue satisfactorily for both sides. By the spring of 1859, American troops had been stationed on the island and 18 Americans had staked claims on prime sheep-grazing land. The British considered them squatters and their claims illegal.

On June 15, 1859, the tense situation exploded. An American farmer, Lyman Cutlar, found a big pig rooting in his garden, eating his potatoes. Cutler shot and killed the pig, which was owned by Charles Griffin, who ran Bellevue Farm. Cutlar offered Griffin $10 in compensation, but Griffin wanted $100. Cutlar argued that he shouldn’t have to pay for the pig at all because it had trespassed on his property.

When British authorities threatened to arrest Cutlar and evict his countrymen, American settlers demanded military protection from Brigadier-General William Harney, in command of the Department of Oregon. The anti-British Harney dispatched 64 soldiers to San Juan Island to prevent British ships from landing. James Douglas, governor of Vancouver Island, concerned that American squatters would occupy the island if not kept in check, sent three warships and ordered Rear Admiral Robert Baynes to land marines on the island and engage the Americans. Baynes declined, citing the foolishness of involving “two great nations in a war over a squabble about a pig.”

By the end of August, there were 461 American troops in place with 14 field guns and eight 32-pounder naval guns opposing five British warships carrying 52 guns. The Americans dug in and the British fired practice shots into the bluffs along Griffin Bay. Commanding officers were ordered not to fire the first shot, but to defend themselves if necessary, instigating a battle of taunts and insults as each side tried to goad the other into aggression. It was amusing for tourists arriving on excursion boats from Victoria and the officers from both sides who shared whisky and cigars at Charles Griffin’s home.

When news of the situation reached Washington and London, shocked officials set about defusing it. President James Buchanan sent General Winfield Scott to negotiate with Governor Douglas. They reached a settlement in November, agreeing to reduce their presence to no more than 100 men on each side, with the British camp established at the north end of the island and the American camp at the south. The two camps had an amicable relationship for 12 years until the matter was turned over to Kaiser Wilhem I. He referred it to a committee of three that met in Geneva for most of a year before deciding in favour of the United States on October 21, 1872, establishing the marine boundary through Haro Strait.