In 1962, George Woodcock, the Vancouver literary and social critic, published what turned out to be his most famous book, one that has stayed in print ever since. He called it Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. He always described himself as a “philosophical anarchist,” a phrase coined in reaction to that stereotype of 19th-Century political cartooning — the black-bearded bomb-throwing anarchist, probably Jewish and certainly foreign, lurking in the urban shadows.

But by using the word “libertarian” in his subtitle, Woodcock was able to further emphasize the serious and pacifist nature of his book, for in those days “anarchist” and “libertarian” were not necessarily contradictory terms. Although even many educated people still clung to the ridiculous generalization that all anarchists were (and are) violent by nature, “libertarian” was another matter. To the politically educated, it simply meant self-determination, freedom from bureaucracy, the right to live as you please so long as you don’t hurt anyone else. It called to mind, well, Thomas Jefferson (OK, not the slave-owning side of Jefferson, but the other part).

Since the 1970s, however, these two words, “anarchism“ and “libertarianism,“ have split apart. Adherents of the one -ism almost always seem to antagonize those of the other, though in many or most ways, the two groups have more in common than either will admit. This is the take-away from The Libertarian Mind: A Manifesto of Freedom (Simon & Schuster Canada, $34) by David Boaz, a prolific writer on the subject. Without even including the A word in his index, Boaz cannot help but find obvious similarities between the two outlooks. There are naturally some cranks in both camps, but speaking generally, libertarians and anarchists not only favour the smallest practical amount of government, but are also skeptical of military intervention and wish to end imprisonment for most non-violent crimes. They want to advance racial and sexual equality and improve health care.

U.S. libertarian-fiscal conservatives widespread

Boaz writes: “In studies I have co-authored on ‘the Libertarian vote’ [here he refers not to the –ism, but to the political party of the same name, about which more later on] we have found that some two to four percent of Americans say that they’re libertarian when asked. But 15 to 20 percent — 30 million to 40 million Americans — hold libertarian views on a range of questions.” He cites a Gallup poll that asked Americans whether they would define themselves as fiscally conservative and socially liberal and found “that 44 percent of respondents — 100 million Americans — accept the label.” In the immediate aftermath of 2008, he notes, one saw identical banners, with identical mottoes, at Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street events. But he also confesses that “the libertarian vision may sound otherworldly, like a doctrine for a universe of angels that never was and never will be.” Which is precisely what has long been said about anarchism as well.

The Tea Party’s piggy bank

The Libertarian Mind comes out of Boaz’s work at the Cato Institute, the libertarian think-tank based in Washington, D.C., an organization funded largely by the notorious Koch brothers, Charles and David, whose super-PACs are the Tea Party movement’s biggest piggy bank. This fact alone, of course, is enough to provoke grimaces and worse from Americans who think of themselves as progressives and therefore see the Kochs as distorters or perverters of democracy. Boaz shrewdly forgets to mention the Kochs in his book. Instead he states merely that libertarians “believe that the most important political value is liberty, not democracy.” He cites, a bit lamely, I find, the example of India, “the world’s largest democracy, yet its commitment to free speech and pluralism is weak and its citizens have been enmeshed in a web of protectionist regulations — happily reduced in recent years — that limited their liberty at every turn.”

Later, he writes: “In modern American political discourse, we want to assign everyone a place along a spectrum labelled left to right, liberal to conservative. So is libertarianism left or right?” Most people, except those who renounce labels or hide from them, would say that libertarians are on the right, just as anarchists are on the left. Perhaps the real question is how the two can have so many ideas in common while being at odds with each other. How indeed. Two of the finest men I’ve ever had the pleasure to know were Neil Reynolds and the aforementioned George Woodcock. The former was once the leader of the Libertarian Party of Canada (and the publisher of this magazine); Woodcock was the 20th Century’s best-known writer on anarchism. They never met, but admired each other by long distance.

Forerunners

The bulk of Boaz’s book is a discourse on what Americans call liberty and others call freedom. It’s a thoroughly American work, but makes occasional mentions of other nationalities. For example, Boaz cites a passage, often quoted by anarchists as well, in the Tao Te Ching from China in the 6th Century BCE: “Without law or compulsion, men would dwell in harmony.” But his nods to other cultures are few and fleeting, as the libertarian movement in the U.S. speaks only in an American accent while anarchism is polyphonic.

It may well be true, as Boaz says, that “early America’s libertarianism came from England and Scotland,” but it did so by way of many different figures. He chooses to mention only one by name: Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). She was the mate of the English proto-anarchist thinker William Godwin and the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (who wrote Frankenstein and was the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, the poet, who died fighting to free Greece from the Turks). Since the 1970s, there has been a great revival of interest in the story of Wollstonecraft senior, an indication that American libertarians retain a strong focus on congressional politics, while anarchists, on this continent and elsewhere, have shifted from the question of state authority to such issues as climate change and feminism.

One example of this trend in anti-authoritarian thinking is Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley by Charlotte Gordon (Penguin Random House, $35), the latest of many modern studies of these two women and their ideas. Similarly, Janet Biehl’s Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin (Oxford University Press, $34.95) illustrates how Bookchin applied his own brand of anarchist thought to questions of sustainability, decades before such discussions became common.

If anarchism and libertarianism are somehow connected at the core, why are they so different? The answer isn’t a simple left-right split, but rather a question of the starkly different ways each came into being as a social movement. The Russian nobleman and scientist Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921), whose biographer was George Woodcock, was the person who made anarchism a genuine -ism. That is to say, he made it into a coherent philosophy that could be applied like a grid to study any issue. Russia was always a breeding ground for anarchists because the place was so susceptible to rule by despots. Generally, though, as Woodcock liked to point out, anarchism flourished, if that’s the word, in countries that were hot, predominantly Roman Catholic and ruled by monarchs or generals — in some cases, all of the above. One couldn’t be an old-style anarchist unless one had harsh authorities against whom to rebel.

Couple’s botched assassination attempt

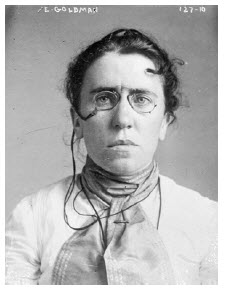

In Europe for a few years in the late 19th Century and first decade of the 20th, there were, in fact, cartoon anarchists throwing bombs at people — giving the movement a bad name that would never be completely erased. In the U.S., by contrast, most acts of what anarchists called “propaganda by the deed” (what we would call primitive domestic terrorism) arose from industrialization. One of the most infamous involved the agitator, speaker and women’s rights advocate Emma Goldman (1869–1940) and her comrade and sometimes lover, Alexander (Sasha) Berkman (1870–1931). There are numerous biographies of Goldman, including a concise recent one by Vivian Gornick — Emma Goldman: Revolution As a Way of Life (Yale University Press, US$16.95 paper.) It is part of Yale’s “Jewish Lives” series, which explores the careers of prominent Jews not generally known foremost for their place in Jewish religion and culture (for example, Groucho Marx or George Gershwin).

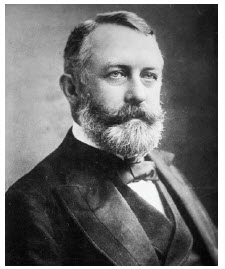

Paul Avrich, an important academic historian of anarchism, was hard at work on a dual biography of Goldman and Berkman when ill health caused him to ask his daughter, Karin, to take over the project. The result, Sasha and Emma (Harvard University Press, US$35), describes Berkman’s unsuccessful attempt to rub out the Pittsburgh steel magnate Henry Clay Frick in his office in 1892 as Goldman stood by: a protest against Frick’s use of Pinkertons to murder striking workers. The attempt became something of an opéra bouffe, for Berkman, who, although armed with a pistol and knife, proved an almost comically inept assassin. He was sentenced to 24 years in prison, where he was shunned by many of the other working-class inmates as a nuisance, a busybody and a bumbler who only made matters worse. While in custody, Berkman and a few others managed to publish an in-house radical newsletter that has now been gathered together for the first time as Prison Blossoms: Anarchist Voices from the American Past (Harvard, $26.95). Berkman and Goldman were later imprisoned for opposing U.S. entry into the Great War, and after the Armistice were deported to Russia by the young J. Edgar Hoover. To her credit, Goldman instantly saw the dystopian horror of the new Soviet Union and wrote books about it. Kicked out of two countries, she spent most of her last days in Canadian exile, dying in Toronto.

Political cousins

That Frick’s shooting was not necessarily characteristic of radical violence at the time is seen by comparing the event with, say, the once-famous march of Coxey’s Army the following year. The U.S. was in a deep recession and, as Benjamin F. Alexander explains in Coxey’s Army: Popular Protest in the Gilded Age (Johns Hopkins University Press, US$19.95 paper), a harmless agitator named Jacob Coxey led a peaceful march from rural Ohio to Washington, D.C., demanding that the government spend its way out of the trouble by investing in infrastructure projects. Sound familiar? It raised quite a fuss at the time.

Of course protest, whether peaceful or violent, has often sizzled on the margins of democratic politics and sometimes burst into flames. For the past several years, there has been a wave of proud retrospection about the American civil rights movement of the early 1960s. At present, we are beginning to see studies of American “revolutionary” groups of the later 1960s and 1970s, a generation before the idea of terrorism took on an international connotation. Bryan Burrough’s book Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence (Penguin Random House, $34.95) recalls a time that now seems safely obsolete, though I was jarred by his description of one particular event: the accidental blowing up of a Greenwich Village townhouse on West 11th Street, where members of the Weather Underground (aka the Weathermen) were trying to build a bomb. I used to live just up the street.

By what logic does this return me to the question of libertarianism? Well, I just want to make one clear distinction between libertarianism and the Libertarian Party and another one between the American and the Canadian parties. In the U.S., electoral libertarianism, while hardly a force in political life, certainly has a presence. The party was founded in 1971 and, at the time I’m writing this, has 152 people in office in 33 states, all of them in municipal, county or state jobs, including 37 in Pennsylvania (a Libertarian hotbed, evidently) and 17 in California. By contrast, the Libertarian Party of Canada, founded in 1973, ran eight federal candidates in 2002 who drew a combined total of 1,949 votes. But in our federal election last October, the party fielded 67 candidates in seven provinces. One Alberta hopeful, one who perhaps fitted the American mould a little more closely than most, encouraged donors in his riding by enrolling them in a lottery. The lucky winner, the day after the election, was to be given a $1,200 rifle. The Globe and Mail reported that the man “checked with Elections Canada […] and was told it had never been done before, but it did not run afoul of any election rules.”

And briefly…

Most people who closely followed events in Myanmar since the already repressive regime cancelled elections in 1988 hoped that the junta would eventually fall. Many imagined that, in the usual manner of these things, a new generation of youngish colonels would organize a coup against the elderly generals and supplant them. Instead, the geriatric generals, who had held control since 1962, sort of gave themselves up without actually going away. They promised to restore at least somewhat-free elections. But the title of Delphine Schrank’s book, The Rebel of Rangoon (Public Affairs, US$26.99) isn’t about the democratic angel Aung San Suu Kyi. Rather, “the rebel” is a sort of generic pseudonym for a disparate batch of underground grunts who struggled to keep hope alive. Schrank, who reported from Myanmar for the Washington Post, writes densely and with passion and depicts the story she has to tell in a fragmentary way, “because the actions of its protagonists are fragmentary.” The result is that the prose isn’t always as clear as it should be. Rosalind Russell, who covered much of the same territory for the Independent in Britain, tells the story more accessibly in Burma’s Spring: Real Lives in Turbulent Times (Thistle, US$19.95 paper).

Eduardo del Buey, who now lives in Washington, D.C., is a former career Canadian diplomat who served in half a dozen widely scattered overseas missions, working as a communications director and official spokesman. His book, Spokespersonry (Friesen Press, $16.95 paper) distils a career’s worth of knowledge about how to prevent the wrong message getting out — or how to repair the damage if it gets out anyway. He includes numerous case studies. The book comes on the heels of a somewhat similar book of his, aimed more at the corporate rather than the diplomatic world: Guerrilla Communications (Friesen, $29.95).

George Fetherling is a novelist and cultural commentator.