Now that the Trudeau government has been in power for more than 150 days, we have begun to see what shape Canada’s foreign policy will take under its leadership. There have been some surprises, while other actions have mirrored campaign promises and resurrected classic liberal values from the past.

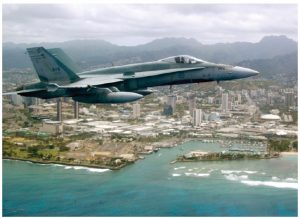

The biggest move so far — and certainly the one that has gotten the most publicity — is the retooling of the Canadian commitment to fighting ISIS. In the election campaign, the Liberals promised to withdraw our CF-18s from the international coalition and to focus instead on “Canada’s strengths.” Canada’s contribution to the aerial mission was essentially negligible, making up only about three percent of all airstrikes. However, critics argue that withdrawing our fighters symbolizes weakness. Indeed, a number of jihadi propaganda sites highlighted the Canadian withdrawal as a victory and as a sign of a lack of Western resolve to continue the fight.

While the Liberals made a solid new commitment, by tripling the number of military trainers, more than doubling the number of soldiers on the ground, and upping the humanitarian contribution to the mission by hundreds of millions of dollars, they were still caught flat-footed when trying to explain why it was also necessary also to end the air mission. Critics have noted that Canada can “walk and chew gum at the same time.” However, most recognize the rationale for ending the air campaign is rooted in politics: It was an election promise, and the Liberals wanted to keep it.

The government caught a break when our U.S. allies declared their approval for the revamped mission. Yet, time will tell whether public support for a more dangerous and costly mission in the Middle East is well received by the Canadian public. The government has also announced a much-needed defence policy review, slated for completion in 2016. Expect the review to re-prioritize Canada’s military engagement capacity and strategy more towards peacekeeping and peacebuilding than in recent years.

The other story that dominated the headlines was Canada’s commitment to resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of 2015. While not meeting the timeline, due to capacity and security problems, the government has made good on its promise and, generally speaking, the move has mixed levels of public support in Canada. A recent poll by Angus Reid indicates that more than 70 percent of Canadians feel the target is too high, however another poll shows that a slim majority (52 percent) supported the plan to take in 25,000 refugees by the end of February. The evening news features feel-good news stories of refugees welcomed to their new communities. However, not everything has gone as smoothly as hoped, with housing shortages and refugees’ difficulty adapting to their new surroundings creating some problems for the new arrivals. Nevertheless, Canada’s international image was bolstered by scenes of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau welcoming refugees at the airport, in contrast to polls of likely Republican voters in the U.S. who support Donald Trump’s call to cease immigration by Muslims until the country’s security apparatus is deemed adequate for clearing them for entry.

Canada’s welcoming of a large number of Syrian refugees (although 25,000 is a drop in the bucket when contrasted against the more than 55 million refugees around the world) appears to be a political boon for the Liberals.

Both less surprising and less controversial is the Trudeau government’s move to re-engage multilaterally. The first large-scale public demonstration of this commitment in action was the COP21 Climate Change Conference in Paris at the end of 2015. Canada sent a large delegation that was very well received. Canada has received “Fossil Awards” as a laggard on climate change action for the past several years (including this one).

However, that looks set to change as Environment Minister Catherine

McKenna addressed concerns over Canada’s past behaviour and pointed to future constructive engagement both at home and abroad. Indeed, the issue appears to be a priority for this government, with a new branding for the ministry, which actually uses the term “climate change,” as well mentioning it in the preamble of PMO mandate letters to ministers, outlining commitments and ministerial goals.

Less visible is the work being done behind the scenes to reinvigorate Canada’s foreign service and the country’s mission to the United Nations and other multilateral bodies. The PMO reportedly contacted Canada’s network of ambassadors around the world and lifted the strict communications rules that had been imposed by the previous government. Vetting of public speeches by the PMO is no longer required, and it vows to listen to the advice of diplomatic staff on the ground when it comes to dealing with relevant international issues.

There has also been talk of renewing the junior professional officer program, which allows young Canadians to work for UN bodies in a highly regarded program that was cancelled in 2010. The Liberals have further reached out to youth, particularly those in academia, with an “International Policy Ideas Challenge.” In partnership with the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Global Affairs Canada has challenged graduate students to propose, in a short pitch, their best foreign policy ideas. The top 10 students selected will be invited to present their ideas and the top three will receive cash to further develop the proposals, which will then be used within the department.

There was a shunning of academia under the previous government, and of public engagement generally. For example, it pared back and cancelled several key research funding programs and discontinued small, but meaningful, annual tours and consultations aimed at informing graduate students about the work environment and mandate of various central agencies. So, although this is a small step, it represents a big shift in attitude. The next budget will most likely see renewed funding to foreign affairs, possibly targeting the enlargement of the Canadian permanent mission to the UN as well as the reopening of consulates and embassies that were closed in recent years for financial reasons. An official foreign policy review is viewed by some as long overdue and best undertaken together with the defence policy review this year to ensure coherence across departments.

Canada’s international development policy underwent huge shifts in the past decade. One example is the sudden suspension of all aid funding to Haiti and the move towards public-private partnerships with mining companies in Africa, whereby Canadian aid was refocused towards appeasing communities affected by large-scale mining projects. Moreover, in 2014, $125 million of aid funding was returned to the Finance Department unspent, and Canada’s level of foreign aid as a percentage of GDP dropped. A shift away from economic interests and trade promotion is expected, with more funding to the most impoverished countries, especially those located in sub-Saharan Africa. Evidence-based policy-making decisions across the board are likewise expected to make a resurgence, with centres such as the International Development Research Centre playing a greater role in government policy. More generally, we can expect more openness and less secrecy. Publishing the mandate letters to ministers was the first step and the increased accessibility of the ministers has been evident. To be sure, reshaping Canada’s international image is a priority item for this government. The day after the 2015 election, Justin Trudeau made a clear statement to the rest of the globe: “I want to say this. To this country’s friends all around the world — many of you have worried that Canada has lost its compassionate and constructive voice in the world over the past 10 years. Well, I have a simple message for you: on behalf of 35 million Canadians: We’re back.”

Joe Landry is a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar and PhD candidate at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University.