“Every time I slip into the ocean, it’s like

going home.”

This quote from leading American oceanographer Sylvia Earle reminds us that the fate of humanity — our fate — inevitably depends on the fate of the oceans that cover almost 71 percent of our planet. In fact, it is misleading to speak of oceans as plural, since the various oceans constitute one of the two large planetary life systems, the other being the atmosphere.

As Earle implies, we are of the ocean. The processes that eventually gave form to Homo sapiens started billions of years ago in the primordial ocean that covered the planet, and to this day, with many more to come, humans depend on the ocean and its interaction with the atmosphere.

The most obvious form of this oceanic reliance is the aquatic life that we pull from the seas for our nourishment and survival.

But if the ocean is a pantry that has sustained countless human communities since time immemorial, it has long ago also become a proverbial garbage dump for every substance imaginable, including the very gases threatening to raise

planetary temperatures to catastrophic levels.

In making it a dumping ground, we are destroying a complex, yet delicate web of dependencies that currently sustains millions of species, including our own. Despite our immense ability to analyze and modify our natural surroundings in anticipation of future material needs, we cannot escape the fact that we ultimately live in a world of finite resources and the ocean is perhaps the most precious and essential one.

It is a source of prosperity and beauty. It is one of reasons the late astronomer Carl Sagan called our planet a “pale blue dot” after seeing a picture of Earth as taken by Voyager 1 from the distant reaches of our solar system. Without it, we would not be. Yet, we are also its greatest threat and this list aims to draw attention to the many ways in which we threaten our oceans, ourselves and future generations.

This list claims to be neither comprehensive nor authoritative. By ranking threats, it actually creates the impression that some issues are less pressing than others — a faulty perspective, if ever one existed. All of the issues listed here deserve our attention now.

1. Inadequate institutions

The oceans of the world are invaluable assets that are rapidly losing their value through our actions. Yes, our activities have always affected the oceans, but this fact does not account for the havoc that modernity has heaped upon them. The problem is not human use of the oceans, per se. Rather, it is a question of unsustainable human use.

Reasons for this are many and include the absence of effective, coercive institutions that insure the oceans against what Garrett Hardin has called the tragedy of the commons in his famous eponymously titled essay. It occurs when humans have to manage resources without definitive ownership, which is the case with most of the oceans. (According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 64 percent of the surface of oceans and almost 95 percent of their volume lie beyond national borders.)

Common access to any resource, Hardin argues, encourages rational individuals to maximize their use of that resource, because they reap almost all of the marginal benefits. Simultaneously, the costs of exploitation are shared. Profits are personalized, costs socialized.

“Therein is the tragedy,” writes Hardin. Common users find themselves “locked into a system” that “compels” them to increase their use of a common resource “without limit — in a world that is limited.” So “freedom in a commons,” he says, “brings ruin to all.”

The international community has recognized this problem and the literature bursts with appeals to improve oceanic governance, an undefined collection of “rules, institutions, processes, agreements, arrangements, and activities,” as the European Commission says in a position paper.

Central to this collection is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), created in 1982. This landmark instrument establishes a comprehensive legal framework that regulates all ocean space, its use and resources. Notably, it permits nations to create exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of no more than 200 nautical miles. This “fencing” allows nations to conserve their local fisheries. The UNCLOS also includes royalty schemes designed to benefit developing nations from resource projects beyond their EEZs. However, the UNCLOS has received criticism for weak enforcement mechanisms, which rely on national legislation to implement its provisions. Overall, actual developments cast serious doubts about the effectiveness of existing governance.

Consider illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) forms of fishing, which are among the greatest threats to marine ecosystems, according to the FAO.

“Motivated by economic gain, IUU fishing takes advantage of corrupt administration and exploits weak management regimes, especially those of developing countries lacking the capacity and

resources for effective [monitoring, control and surveillance].” Hardin could not have described it better himself.

2. Climate change

According to leading scientists, Earth has entered the Anthropocene, a proposed term to describe the geological epoch in which humanity itself has become a major geological force that will shape Earth for thousands, if not millions, of years.

The enormous, ever-expanding use of fossil fuels defines the epoch, which many scientists say started in the late 18th Century, when the invention of the steam engine set off the Industrial Revolution. It created a cycle of expanding economic activity, resource extraction and population growth that continues to release large volumes of heat-trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as CO2 (carbon dioxide) and CH4 (methane) into the atmosphere.

Levels of carbon dioxide hovered between 270 and 275 parts per million before industrialization. They reached 350 parts per million in 1950. Current levels hover around 380 parts per million and predictions point towards 500 parts per million by 2050.

Overwhelming scientific evidence has since linked this spike in GHGs with rising global temperatures — anthropogenic (human-made) climate change. According to the latest report by the International Panel on Climate Change, “continued emissions of (GHGs) will cause further warming and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems.” This prediction includes the oceans, which absorb 90 percent of the excess heat that GHGs create.

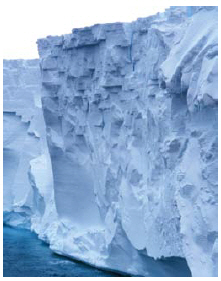

The effects of climate change on the oceans will be numerous. They include, most obviously, higher sea levels, as many, if not most, of the remaining glaciers melt away and release their water. A paper published in Science in July 2015 says sea levels might rise at least six metres, even if the world manages to meet its target of limiting future temperature increases to two degrees Celsius by 2100 — and that’s a big if.

Several studies have since said that the oceans might be rising faster than previously predicted. Higher temperatures also mean more intense storms. More intense storms, in turn, raise the likelihood of damaging floods and storm surges. Combined, the reinforcing effects of rising sea levels and stronger storms threaten catastrophic physical damage to the islands, river estuaries, shorelines and arctic ice-shelves on which so many different life-forms depend for their survival. This web of dependency, of course, includes humans and their habitats.

Climate change will also make the oceans warmer. Rising temperatures in turn may impact the reproductive cycles or nutritional needs of oceanic species. Yes, some may be able to adapt by migrating to colder latitudes. But many will likely fail to adapt through a sheer lack of time. As the literature notes, humans are changing their planet in a rapid, increasingly unpredictable manner.

Finally, climate change will make the oceans more acidic. As Thomas Lovejoy, inventor of the term biodiversity, told Elizabeth Kolbert of The New Yorker in her masterful account of climate change, Field Notes from a Catastrophe, this acidification “is going to send all kinds of ripples through marine ecosystems.” They are described below.

3. Acidification

Near a long list of threats to the oceans, we find acidification, or “global warming’s equally evil twin,” Kolbert writes. The process of acidification is as straightforward as its effects are serious. Its engine is the exchange of gases between the global atmosphere and oceans. In a state of equilibrium, the oceans absorb (roughly) the same volume of atmospheric gases as they release into the atmosphere. This

exchange, however, has become increasingly “lopsided” as more CO2 enters the water than comes out, Kolbert writes.

When CO2 dissolves into water, it forms carbonic acid — a “relatively innocuous form” of acid bubbling in countless carbonated beverages.

But the growing imbalance between the amount of CO2 that oceans absorb and release means that they are becoming more acidic — 30 percent more since the Industrial Revolution.

“If current trends continue, by the end of this century, they will be 150 percent more acidic,” Kolbert says. This rise, in nothing less than a “geological instant,” will have drastic consequences. It will likely ravage calcifiers, a class of marine organisms that use calcium carbonate to develop shells, exoskeletons and protective coatings. They include clams, oysters and starfish, among others. Acidification will especially devastate reef-building corals because it will deny them the building blocks of life itself.

As Kolbert writes, acidification precludes the very possibility of reefs, a potentially devastating development for all life on the planet. Coral reefs cover 0.1 percent of the ocean, but sustain 25 percent of all marine fish species, many of which feed humans. Once the reefs are gone — Kolbert says one third of all reef-building corals are heading towards extinction — many of the estimated nine million species of marine life that rely on them for shelter, food and breeding space will disappear as well. This possibility has prompted demands for drastic cuts to CO2 emissions to prevent acidification.

Without such measures, future oceans might be inhospitable for many of the species that we know today, with devastating consequences for all of planetary life. Oceanic acidification, Kolbert says, has often coincided with dramatic crises “in the history of life, including the end-Permian extinction, 250 million years ago, which killed off something like 90 percent of all species then on the planet.”

Kolbert has since written a Pulitzer Prize-winning book titled The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History that argues that we currently find ourselves in the midst of such a mass-extinction event. Notably, she dedicates two chapters to the effects of acidification. Unfortunately, it is impossible to reverse the acidification that has already occurred.

“Even if there were some way to halt emissions of CO2 tomorrow, the oceans would continue to take up carbon until they reached a new equilibrium with the air,” Kolbert writes in Field Notes.

According to Britain’s Royal Society, it will take “tens of thousands of years for ocean chemistry to return to a condition similar to that occurring at pre-industrial times.”

4. Unsustainable fishing

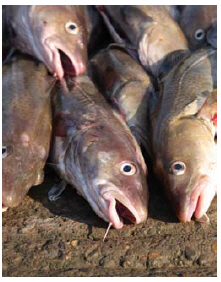

A positive feedback loop constitutes a cycle whose effect reinforces the cause. This concept best describes the current state of global fish stocks.

As World Wildlife Fund (WWF) International general director Marco Lambertini writes in the foreword of the Living Planet Report 2014: “Humanity is collectively mismanaging the ocean to the brink of collapse.”

According to the WWF, overfishing and climate change have more than halved all marine populations since the 1970s, with overfishing bearing the larger share of the blame.

When the WWF specifically looked at the fish species that make up to 60 percent of protein intake in coastal countries, it found populations “in a nosedive.”

Yet demand for fish continues to rise as the human population surges towards an estimated figure of nine billion by 2050. Rising demand for fish, combined with a lack of alternatives and large fishing fleets that receive taxpayer subsidies of up to US $35 billion, have triggered what the WWF calls a “race to fish.”

This competition for new catch is depleting many coastal fisheries and has sent fishing fleets deeper into international waters, where they seek new species in new areas. As the WWF says, “only the deepest and most inaccessible parts of the oceans are yet to feel the pressure from fisheries.”

Technology, as in any race, also plays a part. Decades ago, it was impossible to fish in depths below 500 metres. Today, vessels can fish in depths of up to 2,000 metres. But fish populations at greater depths grow more slowly and reach maturity later than species in shallower waters. In short, they are not as productive. Once those stocks have collapsed, as they surely will, they will take a long time to recover, if they ever do.

Fishing fleets, meanwhile, will have long sailed for other areas, thereby accelerating the process of depletion, as more ships increasingly chase fewer fish, further diminishing stocks. This course constitutes the very definition of a feedback loop.

This exhausting cycle could spell nothing less than disaster for people in developing nations for at least two reasons. First, fishing remains an indispensable food source in many of those countries, and declining fish stocks would further undermine their food security, a development rife with political consequences. Second, their shorelines have increasingly attracted industrial-scale fleets from developed, primarily European countries, including Spain, Portugal, Germany and the Netherlands.

Other culprits include trawlers from Japan, South Korea, Russia and, increasingly, China. Equipped with superior technology, these fleets engage in a range of what the literature calls illegal, unregulated or unreported (IUU) forms of fishing that further deplete stocks to the detriment of locals, who often lack the resources and means to defend themselves and their territories, as many of their governments are either ineffective, corrupt or both.

As the FAO notes in a 2014 report, IUU fishing “remains a major global threat to the long-term sustainable management of fisheries and the maintenance of productive and healthy ecosystems” and it “may exacerbate malnutrition, food insecurity and even hunger in some places and losses of livelihood and revenues in others, extending its impact to the trade chain and beyond.”

Populations along the western shore of the African continent appear particularly vulnerable to the practice of “ocean-grabbing,” whereby perpetrators pirate fish from the shores of developing countries through shady access agreements, unreported catch and incursions into protected waters. According to the 2014 Africa Progress Report, it costs the region of West Africa US $1.3 billion annually.

5. Pollution

In the Island of the Day Before, the late Italian writer Umberto Eco describes a mysterious Pacific Island that remains just beyond the physical reach of the book’s main character, Roberto della Griva, the sole survivor of a French sailing ship that sought to discover an accurate method of determining longitude.

Eco’s imagined island very much describes the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a shifting domain of modern detritus in the northern Pacific that consists of solid debris, liquid chemicals and tiny pieces of plastic that float “like confetti in the water” as the New York Times put it in 2009.

While science can sense its existence, its scope remains speculative. Size estimates range widely, to the point of uselessness. Yet no one doubts the genesis of its being — human garbage, caught in the steady currents of the North Pacific Gyre. Similar vortexes of garbage gyrate in the Indian Ocean and North Atlantic and their presence alerts us to the larger problem of human-made pollution that threatens aquatic and, ultimately, human life.

Forms of pollution vary. They include plastics, chemicals and heavy metals. Plastics alone constitute a major problem. According to one peer-reviewed estimate, some five trillion plastic pieces with a total weight of 250,000 tonnes currently float in the oceans. Many organisms consume these pieces and they eventually work their way up into the food chain.

The same process also introduces even more dangerous substances to human diets.

Consider the following ironic example: According to The Guardian, the presence of damaging levels of pesticides, such as aldrin, dieldrin and chlordane linked to birth defects, neurological harm and some cancers, prompted Japan, which defies the ban on commercial whaling, to dump imported whale meat from Norway (one of two other countries, Iceland being the other) that continue to hunt whales for commercial reasons.

The toxins had entered the animals through the food chain and Japan’s ban has forced Iceland to cancel this year’s hunt of endangered North Atlantic fin whales. This temporary suspension, however, will be of little comfort to the whales, who remain contaminated. While these pesticides offer a “morbid kind of defence” against those who still have a taste for their meat, they wreak havoc with the whales’ immune and reproductive systems, according to the Guardian.

Excessive nutrients from agriculture, sewage and industrial production, meanwhile, can trigger deadly algae blooms (eutrophication). These blooms (so-called red tides) decimate aquatic life and deplete oceanic oxygen levels to create “dead zones” incapable of sustaining life. (Dissolved oxygen levels drop after algae have died and decomposed). While hypoxic zones can occur naturally, they tend to occur around areas of human settlement. Regions with prominent dead zones include the Eastern Seaboard of North America, the northern Gulf of Mexico, the Baltic, the coastlines of southern Japan and the eastern seaboard of China.

Overall, land-based sources account for 80 percent of all marine pollution and researchers predict that the resulting dead zones will only grow larger in the future, as the global population grows and many regions continue to dump untreated water into the oceans. According to the fourth United Nations World Water Development Report, only 20 percent of global wastewater receives proper treatment.

6. Oil and gas

The recent collapse of global oil prices has produced at least one piece of good news, from an environmental perspective. Royal Dutch Shell announced this spring that it would suspend oil and gas exploration efforts in Arctic waters off Norway.

This move, which the company justified, on the basis of slumping oil prices and corporate restructuring following its merger with BG Group PLC, marks only the latest setback for oil and gas drilling in remote Arctic regions. Falling oil prices, environmental protests and economic sanctions against Russia — one of the largest proponents of Arctic drilling — have all combined to dampen enthusiasm for such projects among the corporate leadership of Royal Dutch Shell and various competitors such as ExxonMobil and Chevron.

But this temporary retreat does not constitute a permanent reprieve for oceanic ecosystems. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), offshore or oceanic sources account for one third of all oil and gas extracted worldwide, a figure that the WWF predicts will rise.

This expansion in turn raises the prospect of another disaster, such as the 2010 explosion of British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon drilling rig. Called the worst oil spill in U.S. history, it killed 11 people, injured many more and spilled nearly five million barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

As the U.S. government notes, the disaster disrupted an “entire region’s economy, damaged fisheries and critical habitats and brought vividly to light the risks of deepwater drilling for oil and gas — the latest frontier in the national energy supply.”

This frontier includes offshore drilling in the Alaskan Arctic, a fragile ecosystem that poses a number of unique natural challenges. These challenges, which also arise elsewhere in the Arctic regions of Canada, Russia, Norway and Denmark (Greenland), include remoteness, extreme cold, extended seasons of darkness, hurricane-strength storms and pervasive fog.

These conditions not only limit drilling to the summer months, but also complicate oilspill responses year-round. As the report, titled Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and The Future of Offshore Drilling, notes: “the remoteness and weather of the Arctic frontier create special challenges in the event of an oil spill. Successful oil spill response methods from the Gulf of Mexico cannot be simply transferred to the Arctic.”

The WWF is even more blunt. “There are no proven effective methods of cleaning up oil spills in ice, especially mobile ice. Even without ice, the effects of a spill in Arctic conditions will linger for decades. Oil from the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska still pollutes beaches, more than 27 years later.”

Any response to a future oil spill in the Arctic would also be complicated by the absence of international standards, since the damage caused by such an event might not be limited to the waters of the country where it initially occurred. As the WWF notes, the offshore oil and gas sector “is the least-regulated marine-related industry internationally and regionally when it comes to the environment, safety and compensation.”

The absence of global standards on environment and safety, liability provisions and oil spill response and preparedness appears particularly in developing nations, where governments often fail to meet the most basic environmental standards. However, as the Deepwater Horizon disaster demonstrated, this problem is not unique to places like Nigeria, whose Niger Delta is a modern-day, oil-covered domain. Rusting infrastructure, absent regulations and political corruption have soaked the delta in oil and exposed the people and animals who live there to toxins and other harmful substances.

7. Commercial shipping

The global economy depends on commercial shipping. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), seaborne trade accounts for 80 percent of all trade by volume and more than 70 percent of all trade by value. Total seaborne shipments topped 9.84 billion tonnes and almost 90,000 commercial vessels sailed the seas in 2014.

These ships carry cargo of every kind into all corners of the globe and it is difficult to fathom life without their physical presence, the goods they deliver and the very economic forces that launched them in the first place. Yet, they also pose a present danger to oceans.

Writing in the Hamburg Studies on Maritime Affairs, Markus Kachel divides the damage that ships cause into three categories: damage to oceanic habitats and animals, accidental pollution and operational pollution.

Turning to the first category, ships undermine oceanic habitats and wildlife through direct physical contact. Ship anchors and their connecting chains, some weighing up to five tonnes combined, may instantaneously shred and forever scar large swaths of living coral reef that have required thousands of years to grow and house countless marine species. Ships or their propellers may also collide with large marine mammals, inflicting blunt, often deadly trauma. Northern right whales, of which the International Whaling Commission estimates less than 500 remain, appear particularly vulnerable to ship strikes.

Accidental pollution occurs when ships carrying toxic or hazardous materials spill all or part of their cargo following a sinking, grounding, explosion or collision. Various disasters involving oil tankers have illustrated this form of pollution vividly.

The third, category — operational pollution — includes the dumping of liquid sewage and solid debris, the open-sea draining of tank residues, and the leaching of biocides from anti-fouling paint designed to keep hulls free of marine organisms such as mollusks and algae that impact performance.

Of particular concern is the problem of ballasting, the practice of dumping water when cargo levels are high and taking it on when cargo levels are low. This process stabilizes ships, but also circulates countless marine species such as plankton, algae and fish around the world. While most do not survive this transfer, others thrive and eventually dominate their new ecological homes at the expense of local species.

Commercial ships also contribute to air pollution and climate change through the release of sulphur oxide, nitrogen oxide and carbon dioxide respectively. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) estimates that international shipping accounted for 2.2 percent of global CO2 emissions. While relatively low when assessed per unit of cargo and distance travelled, various forecast scenarios suggest this figure could grow by anywhere between 50 and 250 percent by 2050.

While the maritime transport sector has taken steps to curb emissions, the relevant literature has deemed their efforts so far to be insufficient.

8. Aquaculture

Aquaculture is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can help ensure affordable access to quality food by a large, growing share of humanity. On the other hand, the environmental effects of aquaculture have earned it harsh criticism. This ambivalence appears throughout the literature, including the latest edition of The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report published by the Food and Agriculture Office of the United Nations (FAO) in 2014. “If responsibly developed and practised,” writes FAO’s general secretary José Graziano da Silva, ”developed aquaculture can generate lasting benefits for global food security and economic growth.” Aquaculture certainly accounts for a growing share of global food fish production.

Of 158 million tonnes produced in 2012, aquaculture produced 66.6 million, according to the FAO. Overall, food fish production by way of aquaculture expanded at an average annual rate of 6.2 percent between 2000 and 2012. This figure actually marks a slowdown for the industry, which grew at an average annual rate of 9.5 percent between 1990 and 2000.

Worldwide, 15 countries accounted for 92.7 percent of all farmed food fish, with China responsible for 61.7 percent of all global production. Overall, Asia accounts for 88 percent of total global aquaculture by volume.

This unbalanced economic geography in turn points to aquaculture’s central promise — the provision of protein to almost four billion people (about 55 percent of the global population), including some of the world’s most populous countries, such as China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Japan. In fact, Asia as a whole has been producing more farmed fish than wild catch since 2008, according to the FAO. Other developing regions, including Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America have also seen their respective aquaculture industries grow.

But the potential for aquaculture comes with what might be a high environmental price. Aquaculture continues to destroy valuable habitat. Millions of hectares of mangrove forests have disappeared in Thailand, Indonesia, Ecuador, Madagascar and the Philippines. Aquaculture has also modified hydrological patterns, polluted water for human consumption through excessive waste from farmed fish and contributed to the problem of eutrophication and the enrichment of water through excessive nutrients from fish feed. Eutrophication in turn can trigger deadly algae blooms that deprive affected areas of oxygen.

Finally, aquaculture stands accused of displacing, if not destroying, local marine life by contaminating species through invasive parasites and diseases. This phenomenon has been a consistent source of controversy in developed countries with farmed salmon industries. Consider Canada, where First Nations, environmentalists and scientists have blamed commercial salmon farming for the decline of the Pacific salmon industry. Specifically, they argue that Atlantic salmon species farmed off British Columbia have damaged Pacific salmon species through the spread of sea lice. While these parasites occur naturally, critics of commercial fish farming note that crammed fish pens offer ideal and unnatural conditions for lice to flourish and spread to wild populations.

Notably, Norway offers a preview of what might happen in British Columbia. The Scandinavian country is the largest producer of farmed salmon worldwide, with an annual production of more than a million tonnes. Farmed fish accounted for 67 percent of Norway’s exported fish, according to the Arctic Journal.

Norwegian companies also dominate the farmed salmon industry around the world, including British Columbia, where 90 percent of the industry is in Norwegian hands. Environmentalists have long criticized the Norwegian industry for contributing to the decline of wild Atlantic salmon stocks. They received additional ammunition earlier this year, when the Havforskningsinstituttet Marine Research Institute published new research. It found that the spread of salmon lice from farmed to wild salmon remains the biggest threat to wild stock. It also raised concerns of farmed salmon preying on other species and undermining the genetic integrity of wild salmon.

Overall, a dire picture emerges. Dr. Trygve Poppe, a professor at the Norwegian Veterinary College, told attendees at a conference about farmed salmon in February 2016, that Norway had “very little time” left to save the Atlantic salmon in proposing a total cleanup of Norway’s fish farming industry. Norway’s Fisheries Minister Per Sandberg acknowledged that the situation is “very serious” and promised additional reforms, but environmentalists appear unconvinced as Norway plans to invest more resources in fish-farming to compensate for lower oil prices.

Norway, to quote the Arctic Journal, is putting “all [its] eggs in one pen.” But this strategy also bears risk. Economists predict soaring food prices after an algae bloom killed millions of salmon in farms owned by Norwegian companies. An industry official stressed that the cause of this economic and ecological disaster was a “natural phenomenon” that had “nothing to do with the management of companies.”

While industry leaders have denied a direct link, they have promised to improve practices, which currently include the heavy use of antibiotics, hardly an appetizing acknowledgement.

9. Tourism and development

On its own or as an alternative to other extractive activities, ocean-related tourism can benefit oceanic life and the coastal communities that depend on it. Consider whale watching. A 2010 article published in Marine Policy found 13 million whale-watchers around the world generated US $2.4 billion in total revenues, a figure predicted to increase. If the growth of this industry were to continue at the same pace, it would add more than US $460 million and 5,700 jobs to the global economy. Coastal communities in developing countries — especially in the Caribbean, Latin America and Africa, where fisheries have declined — would see at least some of this growth, the report added.

But for all of its promises, tourism in its various forms also possesses the potential to harm oceanic environments in myriad forms.

While “tourism can be an opportunity for sustainable development,” the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) writes, “poorly planned development of hotels and resorts in coastal areas can result in habitat destruction, pollution and other negative impacts on local communities as well as biodiversity.” The towering hotels that spoil shorelines for many miles in southern Europe, the Middle East and the Hawaiian Islands illustrate that point well.

Consider also the cruise ship industry. While cruise ships represent only a small fraction of the global shipping industry (about 12 percent), these “floating cities” create comparably large volumes of waste. During one week at sea, a moderate-sized cruise ship generates 795,000 litres of sewage, 3.8 million litres of grey water, 500 litres of hazardous waste, 95,000 litres of oily bilge water and eight tonnes of garbage, according to the WWF.

“[This waste], if not properly treated and disposed of, can be a significant source of pathogens, nutrients and toxic substances with the potential to threaten human health and damage aquatic life,” according to a report prepared for the U.S. Congress.

While multiple international protocols, regulations and standards govern the treatment of [this waste], environmentalists lament the lack of a uniform single rule or law to ensure uniformity. Some wastes are regulated well, others less so. Environmentalists also bemoan the lack of adequate enforcement.

Less invasive, more environmentally sound forms of tourism are, of course, possible, but they, too, run the inherent risk of destroying the very things that make them attractive in the first place. Consider the famed Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Tourism supports the local economy and earns Ecuador US $418 million a year. Tourism revenues also help pay for conservation efforts.

However, the WWF notes that a rapid rise in visitors from 40,000 in 1990 to more than 145,000 in 2006 has increasingly strained the islands’ fragile ecosystems. “Rapid development and ever-increasing infrastructure needs, along with higher demand for imported goods and fossil fuels, the introduction of invasive species, immigration and waste threaten the land and waters of the Galapagos.” Studies have also warned that eco-tourism might stress animals and encourage them to be more tame, thereby making them more susceptible to predators.

Tourism, in other words, is both a blessing and a curse.

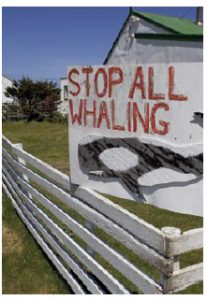

10. Commercial whaling

No other animals have become more symbolic of the need to preserve the environment in the face of human voracity than whales. They, writes anthropologist Niels Einarsson, “sum up and stand for everything that is wrong in the relations between humans and the natural world.” This privileged status of whales in human symbolism is not necessarily new. Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, published in 1851, presents humans as rapacious predators whose obsessive pursuit of cetaceans for commercial purposes invites self-destruction. This argument assigns whales human attributes and sees both species in a symbiotic, transcendental relationship. As Melville says through his character, Ishmael, whales and humans belong to “the living earth” and are “part of a tragic continuum from which nothing is free.” Whether it is appropriate to anthropomorphize whales, as Melville and countless other authors have done since, remains disputable. Several facts, however, are undeniable. First, the real-life inspirations behind Ahab, Starbuck and Queequeg and their subsequent successors in the 20th Century nearly emptied the world’s oceans of whales.

While figures are unreliable, various sources estimate that humans have killed more than a million whales since the emergence of commercial whaling in the 17th Century. Second, several species of whales remain endangered, despite the commercial whaling moratorium of 1986. This reality reflects the historical damage that humans had done in the past and the low reproductive rates of whales themselves. Third, whales are crucial components of the oceanic ecosystem. As Paul Watson, founder of Sea Shepherd, a whale conservation group, told The New York Times in December 2015, “whales are the farmers of the ocean. They bring up iron, nitrogen and other nutrients to the surface. They are part of a system that is millions of years old, and we are in the midst of destroying it.”

The environmental dangers are numerous, as this list shows, and include the whaling fleets of at least three nations that have defied the commercial whaling moratorium — Norway, Iceland and Japan. Of this trio, Japan perhaps draws the greatest amount of international derision, for it has chosen to circumvent the commercial whaling moratorium by labelling its annual minke whale hunt as permissible “scientific research.” A 2014 ruling by the International Court of Justice challenged the scientific legitimacy of this claim, yet Japan persists. During last year’s hunt, Japanese whalers killed 333 minke whales, including 200 pregnant females, according to National Geographic. While minke whales are far more numerous than other species, their fate reminds us that whales are, in the words of Melville, “perishable” creatures, whose potential demise should give us great pause.

Wolfgang Depner holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, where he has taught courses in political science and philosophy. He currently lives and writes in Victoria, B.C., a government and tourist town with a long history of pumping raw, untreated sewage into the Pacific Ocean.