Economic growth stood out for a long time as the big story coming out of China, concealing other aspects of its governance that were problematic, including environmental degradation, rising inequalities, worrying demographic imbalance, abuses of power, corruption and a poor record on human rights. For many years, the Communist Party answered critics of its poor environmental standards, rising income gaps, draconian birth control policies and human rights violations by countering that the country’s poverty alleviation represents an unprecedented achievement in human history in its scale and rapidity. As China enters into a delicate transition towards a consumer-driven pattern of development and its economic growth decelerates, these issues are likely to move to the fore.

China’s approach to growth has come at a very high cost for the environment. Air quality is deteriorating, and not only in Beijing. The indicators of the World Air Quality Index, generated in Beijing, describe China’s capital and dozens of other Chinese cities as “unhealthy,” “very unhealthy,” or “hazardous.” Greenpeace China reveals that the waters of the Yellow, Yangtze and the Pearl rivers are contaminated by industrial waste and are not safe for drinking. A joint report from China’s ministry of environmental protection and the ministry of land resources, released in 2013 stated that close to 20 per cent of the soil of arable land was contaminated. A major reason for these problems, until 2014, was that targets for economic performance mattered more than concern for a clean environment in the promotion of cadres.

Economic growth is not spread equally; although current president Xi Jinping’s predecessor Hu Jintao sought to address the wealth imbalance between the countryside and the cities, and between the coastal provinces and those of the interior, social inequalities remain a major headache for Xi. Although a rising middle class, whose numbers are estimated to equal the entire population of Japan, consumes on a level comparable to Canadians, many more Chinese, whose numbers are the equivalent of the whole African population, live in much more difficult conditions. Of these, the equivalent of twice the population of Japan lives in the cities as migrant workers, without free access to social services like their urban compatriots. China’s ethnic minorities, who total more than three times the entire population of Canada, have also seen economic growth as an attack on their traditional ways of life, and end up living in cities where they find themselves marginalized.

A rapidly aging population

Besides environmental degradation and social inequities, China also faces demographic changes that are slowly evolving and may prove even more intractable in the long run. The aging of the population will affect the dynamism of the economy, while the skewed gender ratio of China’s population will increase social tensions. A combination of factors contributes to distorted demographics. For example, improvements in life expectancy, early retirement ages — men can retire at 60, women at 50 — the small number of children per family, regardless of the recently abandoned one-child directive means that the whole population of China will cease to grow in the next few years. Simultaneously, its workforce has already started to shrink while cohorts of older workers who have started to retire are becoming more populous. As a result, China sees a dramatic increase in the dependency ratio for workers and an end to what was known as the “demographic dividend” that has made its labour force so competitive.

A positive aspect of this social change is that Chinese workers have seen their bargaining position improved in recent years, as they have anticipated that major demographic change. Unfortunately, in this age of a globalized supply chain, this also means that many transnational corporations may relocate outside China, thereby leading to a rise in unemployment and risks of social unrest.

Addressing the challenges

Compounding the above problems are systemic issues of governance. Without any independent oversight except self-discipline, the Communist Party had long lacked an effective mechanism for self-correction. The clearest evidence of this problem is the admission by Party leader Xi himself that corruption represents a life-and-death situation for the CCP (Chinese Communist Party). There is evidence of reliance on criminal elements to help local governments enforce their directives and many cases of land transfer or state asset sale to individuals who benefit from their position in government. This often means forced evictions or firings from jobs without adequate compensation, revealing that abuse of power is rampant at all levels of government.

Although the media, from time to time, comment on the most egregious cases of these abuses, the means to redress them is constrained by a security apparatus that does not tolerate dissent. Under Xi, the campaign against corruption has gone hand in hand with a tightening of the surveillance of human rights lawyers, academics and any individual with influence in Chinese society who appears to represent a threat. The intellectual climate has narrowed and the repression against non-conformist thinkers has escalated. Moreover, Xi is encouraging a revisionist attitude towards the dark years of Mao’s rule: not only Xi himself concentrates power in his hands, but he promotes a view of history that departs from Deng Xiaoping’s narrative that the policy of reform and opening represented a break from the disastrous policies of Mao. Xi suggests that the policy of reforms deepens and improves on what Mao has achieved. This approach, which emphasizes continuity with the previous regime, extends far in the past, as Xi extols the greatness of Chinese culture and, in so doing, promotes an agenda that is nationalist.

A question of regime survival

A question of regime survival

These different issues all represent a major political problem of legitimacy for the regime. The deterioration of the environment leads many to question the merit of economic growth at all cost. For those who are old enough to remember the political campaigns waged in the name of socialism, the continued growth of inequalities since the beginning of reforms represents an unbearable affront to the sense of social justice they were told stood as the foundation of the existing political order.

Deng’s motto that some can get rich first was accepted because it was part of a belief in trickle-down economics. But after decades of reforms and an increasing gap in revenue throughout the country, many see socialist equality as a distant mirage. The aging population represents a more difficult challenge. It is a slow-moving phenomenon and it does not generate stories in papers the way industrial disasters or labour strikes do. Yet, it increasingly affects the livelihood of people, especially that of women, who are still looked at as the “natural care-givers” in contemporary society, in a context in which the provision of accommodation for the elderly is lacking and the traditional values of filial piety are promoted by the Communist Party itself.

There is no reason to doubt that the authorities want to address these issues. It is a matter of regime survival. Environmental degradation, social inequalities and the realities of corruption and abuse of power that accompany them have generated social discontent. The public security bureau under president Hu Jintao and premier Wen Jiabao counted more than 180,000 incidents in 2010, the last year for which these figures were made available. These incidents, which range from public speeches to riots, include all public events where people gather to air grievances. The government sees them as disruptive of political stability. None of this discontent, however, amounts to a credible challenge to the central government.

There is no reason to doubt that the authorities want to address these issues. It is a matter of regime survival. Environmental degradation, social inequalities and the realities of corruption and abuse of power that accompany them have generated social discontent. The public security bureau under president Hu Jintao and premier Wen Jiabao counted more than 180,000 incidents in 2010, the last year for which these figures were made available. These incidents, which range from public speeches to riots, include all public events where people gather to air grievances. The government sees them as disruptive of political stability. None of this discontent, however, amounts to a credible challenge to the central government.

The obstacles to reform remain daunting. Improving the air quality means confronting powerful vested interest groups in the oil and coal industry, for example. These groups, which are connected with relevant ministries in the State Council and in CCP provincial committees, have the ability to resist change imposed by the central government. Addressing social inequalities means undertaking fiscal measures that risk alienating the middle classes. The response to recent efforts by the central government to expand accessibility to higher education to students from poorer families illustrates the problem: parents from wealthy families refuse to give up what they see as their entitlement. Tackling the problem of aging means rethinking government expenditures, which is likely to meet resistance throughout the bureaucracy, because the expansion of social security for the elderly may either require tax hikes or cuts from the budget allocated to other ministries.

Obstacles to reform

The impediments to political reform are inside the CCP leadership, which fears losing control over the agenda. Moreover, powerful vested interests can block the fight for change. For example, there exists a growing understanding in China that the increase in the number of cars and the ongoing reliance on coal use are the primary causes of air pollution.

Most people are now aware that the fumes produced by car engines are a major source of pollutants and that car exhausts need to be modified to mitigate that problem — a change that requires upgrades in fuel quality. The problem, up until 2013, was the refusal of the oil industry to pay the cost of that change, a major roadblock in the transition to cleaner energy. The reliance on coal represents another telling example.

Although coal is clearly seen as one of the most important sources of air pollution, the efforts to rein in that industry have been lacking because of the importance of the coal industry in the economy of the province of Shanxi. The barons of that industry refuse to countenance closing coal mines because, they argue, doing so will lead to massive layoffs and will thereby increase risks of social unrest.

The greatest impediment to reform is, of course, the absence of opposition outside the CCP. There are no organized forces that can articulate political demands for reform. The satellite parties are toothless institutions and the NGOs and civil society work with the expectation that the security apparatus will do everything to make sure that they do not challenge the regime. The growing complexity of China since the beginning of reforms is partly responsible for this. The country faces social divisions and acute cleavages, on the basis of class, ethnicity and region. It is difficult to imagine a united front opposing the CCP in these conditions. Yet, the regime acts as if it fears an imminent breakdown.

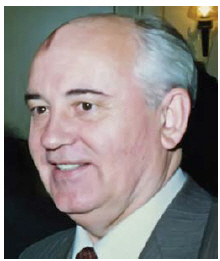

There is little doubt that Xi Jinping and his colleagues still live under the shadow of the Soviet Union’s fall. The lesson they draw from that historical transformation is that the beginning of reform in the USSR under Mikhail Gorbachev has led to the demise of the state. Yet this comparison is flawed: the USSR had already experienced economic decline and stagnation when Gorbachev became leader. The CCP need not harbour that kind of anxiety: China still has some wiggle room because, although the rate of growth may diminish, it still represents one of the best economic performers in the world. The concerns over the breakup of China are also misplaced. The constituent republics of the former USSR represented a far larger proportion of its total population than the combined number of all national minorities in China.

What future direction for the CCP?

There are four possible strategies for the leadership to address these challenges, by order of likelihood.

First, we may see a continued focus on stability and a hardening of the regime. Xi has repeatedly asserted his views and it is clear that he intends to take that line. He blamed Gorbachev for having failed to support communism. The realization that the campaign against corruption generates some resistance may increase the likelihood of a more repressive regime, as Xi fears a backlash against his policies.

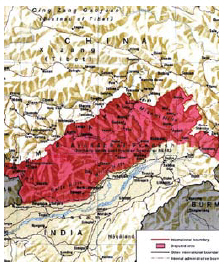

Second, it may decide to promote popular nationalism. This approach reinforces the above, but it comes with some important risks, which Xi has seemed willing to accept so far. These risks include exacerbating tensions in the region, such as claims in the South China Sea that pit China against the Philippines and Vietnam, quarrels with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands, boundary disputes with India and irredentist challenges — those based on the boundaries of the Republic of China between 1945 and 1949 — to Taiwan’s sovereignty. All of these demands are generating expectations from nationalist extremists that the regime may not be able to meet. Chinese nationalism may further risk jeopardizing growth in the long run when other countries in the region start to push back.

A third option is incremental reform. The focus on stability does not exclude this possibility, but regrettably Xi has not shown any evidence that the hardening of his regime is a prelude to such an agenda of limited change. The abandonment of the controversial re-education through its labour system and the one-child policy directive may give the impression that the regime is embracing a program of reform, but in the context of repression against civil society, it is difficult to believe.

The fourth possibility is institutional innovation. A variant of the above, in this case the party decides to be more adventurous with reform and looks at examples of successful transitions wherein the ruling party remains in power following democratic elections. The Party could have considered this option as long as the KMT (Nationalist Party) demonstrated in Taiwan that in the context of free and fair election, a ruling party could keep a majority in the legislature and dominate the agenda — even after losing control of the presidency. But this scenario has become far less attractive now that the KMT is going through a process of decay following its recent loss to the opposition Democratic Progressive Party.

Bibliography

http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/pages/china-in-transition.html?cid=PS_01_12_07_00_01_16_01

http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/campaigns/toxics/water-pollution/

http://www.mep.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/qt/201404/W020140417558995804588.pdf

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/excel/A0201.xls

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/29/china-abandons-one-child-policy

http://thediplomat.com/2013/07/chinas-demographic-dividend-could-end-by-2015/

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/09/business/global/09labor.html

http://www.dw.com/en/us-firms-moving-out-of-china/a-18994088

http://thediplomat.com/2016/02/chinas-human-rights-lawyers-political-resistance-and-the-law/

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/24/academics-china-crackdown-forces-intellectuals-abroad

http://journalistsresource.org/studies/international/china/income-inequality-todays-china

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2015-10/08/content_22130227.htm

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111903703604576587070600504108

http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20160615184248535

http://www.mining.com/china-war-on-coal-to-drive-labour-unrest-report/

André Laliberté is a professor of comparative politics at the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. Author of 50 articles and book chapters, half of which are about China, Taiwan and Cross-Strait relations, he travels regularly to China and Taiwan.