In May 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping set a target for China to become a leading power in science and technology (S&T) by the middle of this century. As he stated at the time: “China should establish itself as one of the most innovative countries by 2020 and a leading innovator by 2030, and become a leading global power by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049.”

In May 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping set a target for China to become a leading power in science and technology (S&T) by the middle of this century. As he stated at the time: “China should establish itself as one of the most innovative countries by 2020 and a leading innovator by 2030, and become a leading global power by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049.”

Xi stressed the role of science and technology (S&T) as a foundation that “the country relies on for its power, enterprises rely on for victories and people rely on for a better life. Great scientific and technological capacity is a must for China to be strong and for people’s lives to improve,” he said, calling for new ideas, designs and strategies in science and technology.

Xi stressed the role of science and technology (S&T) as a foundation that “the country relies on for its power, enterprises rely on for victories and people rely on for a better life. Great scientific and technological capacity is a must for China to be strong and for people’s lives to improve,” he said, calling for new ideas, designs and strategies in science and technology.

Today, China ranks among the world’s most advanced countries in important fields of S&T, including high-performance computing. For instance, in late June 2016, Supercomputer 500, a highly respected annual global high-performance computing (HPC) survey, stated that China continued to maintain its lead in high-performance computer throughput; and that it set a new world record with its latest HPC machine called Sunway TaihuLight. This is the first Chinese HPC machine to be based entirely on Chinese-designed-and-produced semiconductor chips.

Simultaneously, China is in a major S&T transition from an earlier focus on quantity, measuring such factors as numbers of graduate students and scientific papers and citations, to a new thrust on enhancing quality with highly qualified personnel, and moving from breakthroughs in limited areas to a more broad-based approach aimed at contributing to the world pool of scientific and technical knowledge. For example, in July, the Chinese Academy of Sciences announced the initial testing of the newest and largest radio telescope in the world, which has a diameter of 500 metres. China is advancing in quantum theory and related experiments with the mid-August launch of a satellite designed to conduct quantum experiments in space and between Earth and space. Both these instruments are expected to make new foundational discoveries.

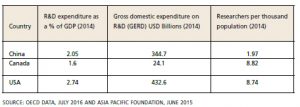

Between 2008 and 2014, China’s gross domestic expenditures on research and development (GERD), an internationally accepted metric on measuring a nation’s R&D intensiveness, rose by more than 20 per cent annually, greatly exceeding that of Canada and the U.S., and most other countries. China increased the ratio of GERD to GDP from 1.5 per cent in 2008 to 2 per cent by 2014. China aims to increase this to 2.5 per cent by 2020.

Between 2008 and 2014, China’s gross domestic expenditures on research and development (GERD), an internationally accepted metric on measuring a nation’s R&D intensiveness, rose by more than 20 per cent annually, greatly exceeding that of Canada and the U.S., and most other countries. China increased the ratio of GERD to GDP from 1.5 per cent in 2008 to 2 per cent by 2014. China aims to increase this to 2.5 per cent by 2020.

By 2012, the distribution of R&D activity across the Chinese economy was 76 per cent performed by business, 15 per cent by research institutes, and 7.6 per cent in the higher education sector. In Canada, by contrast, the business sector only contributed 44.4 per cent to national R&D expenditures, whereas the higher education sector contribution was significantly more than China’s at 41.1 per cent and the federal government S&T amounts to 19.6 per cent of the national total. China’s S&T strategy, programs and incentives are primarily provided by Beijing and the bulk of activities in S&T are under the auspices of the private sector, often in partnership with universities and other research institutes.

China is now the second-largest performer of R&D, accounting for 20 per cent of global R&D as compared to the United States, which accounts for 27 per cent. Just 30 years ago, China’s S&T contribution to global research and development was insignificant.

The table on page 50 illustrates the relative standing of China, Canada and the United States with respect to a number of standard S&T indicators as of 2014. Consider that in 2008, the U.S. GERD was nearly $300 billion more than that of China. By 2014, that gap had narrowed to less than $90 billion. Meanwhile, Canada’s R&D has remained flat over the same period at $24 billion annually.

The granting of university degrees in China has grown faster than in major developed nations, rising more than 300 per cent between 2000 and 2012. Today, China is the world’s biggest producer of research and development personnel. For example, between 2000 and 2012, the number of engineers and scientists more than doubled to nearly two million. However, the gap in the number of S&T personnel per 1,000 individuals is still wide between China and western countries.

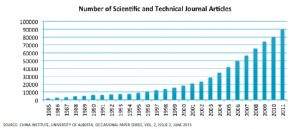

The rapid rise and growth rate of Chinese S&T outputs is impressive. There has been a dramatic increase in the quantity of S&T publications over time (as seen on the graph on page 50.) When compared to world S&T publications, China’s output was 11.1 per cent in 2009 and reached 20.1 per cent by 2014, a nine-per-cent rise in just five years.

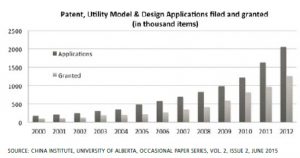

Growth in Chinese patents

China recognizes three classes of patent — invention, design and utility. Thus, the graph above illustrates the dramatic rise in the total number of patents filed and granted in China by domestic and foreign companies. In 2008, there were 400,000 patents granted in China to domestic and foreign companies. By 2012, the number of patents granted rose to nearly 1.4 million, a threefold increase in just four years.

Most domestic Chinese firms granted patents operate in technology-intensive industries (e.g., information and communications technologies and life sciences). Firms such as Baidu, China’s search engine giant, and Huawei, a global telecommunications equipment supplier, represent examples of the leading edge in China’s high-tech industries.

China has gradually improved its intellectual property rights by revising laws and regulations and improving enforcement; but more of the latter is needed through courts, tribunals and increased domestic awareness about patent rights.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs), the relics of a past age of heavy industrialization, are frequently cited as being risk-averse and slow to react in the market. They play a minor role in conducting R&D. As a consequence, SOEs have limited intellectual property compared to private firms in China.

Early in March 2015, Premier Li Keqiang released a report linking entrepreneurship and innovation as drivers of the Chinese economy. In it, he promised to deliver measures that would protect domestic intellectual property rights for all patent holders, and to further open industries to global market competition. Concurrently, the report called for providing financial incentives for researchers to increase innovation and develop inventions.

This last point makes an important distinction between innovation and invention, as they are fundamentally different. Yet most government programs the world over fail to make this distinction by placing an overemphasis on the notion of innovation. There may well be some lessons Canada and others can learn here as this initiative unfolds.

Looking ahead

Despite its many S&T successes, there has been a pattern of ineffective use of national S&T resources despite years of five-year plans. This is primarily due to overlaps in various program objectives and incrementalism in program goals and processes. In addition, China continues to direct both the public and the private economy, and much of the country’s research, by mechanisms such as national plans, regulations, tax policy and subsidies. Venture capital is still a fledgling component of the economy.

These challenges are recognized at the highest levels of government. Actions are forthcoming. The central government is changing its role from designing and managing R&D projects to making national policies and strategies for S&T. As evidenced here, China is rising on foundations based on S&T as a driver for 21st-Century development.

China has led 18 of the last 20 centuries as one of the most innovative and richest countries. And, it is rising again.

Peter MacKinnon is managing director of Ottawa-based Synergy Technology Management. His professional background includes holding positions as a scientist, business manager, entrepreneur, bureaucrat, executive, diplomat, management adviser and academic. He has worked and lived in China for a number of years.