2016 was a difficult year, so why should 2017 be any better? We dug deep and came up with 10 reasons to celebrate this year.

“The time is out of joint — O cursed spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!”

Hamlet Act I, Scene V

Shakespeare’s dithering prince Hamlet speaks these words after meeting what he believes to be the spirit of his father, who urges him to avenge his “foul and most unnatural murder” by killing his usurping uncle, that “incestuous, that adulterate beast” sitting on the Danish throne.

Shakespeare’s dithering prince Hamlet speaks these words after meeting what he believes to be the spirit of his father, who urges him to avenge his “foul and most unnatural murder” by killing his usurping uncle, that “incestuous, that adulterate beast” sitting on the Danish throne.

With these words, Shakespeare captures the resentful disgust through which Hamlet sees the world, a world turned upside down by events beyond his comprehension and control.

We can certainly find considerable evidence that we live in a world of conflict and chaos. Several freedoms, including freedom of the press, are under attack. The global economic climate is anxious as economies everywhere are struggling. Democratic norms and institutions are failing.

Russia has returned to the global stage as an expansionist authoritarian power under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, who has enabled and protected the likes of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. Turkey — which many once considered exemplary for its adoption and promotion of democracy in the Middle East — has imprisoned thousands of people, including political prisoners and journalists, after a failed military coup last year. Long gone are the days when Turkey had no problems with its neighbours.

While China has become a more constructive agent on the international stage — see its role in fighting climate change — it also continues to militarize and seize territory in the South China Sea. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was responsible for 16.1 million refugees in 2015, with 53 per cent coming from three countries: Somalia (1.1 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million) and Syria (4.9 million). Non-state actors such as the Islamic State, the global spread of the Zika virus and urban decay, among other issues, only add to this scenario.

Various real-life characters have since offered their own versions of Hamlet’s complaint, perhaps none more successfully than incoming U.S. president Donald J. Trump.

His promise to “make America great again” was premised on the perspective that the natural order of things is “out of joint.” Trump’s campaign undeniably tapped into a nostalgic longing for the past, but as British writer L.P. Heartley reminds us, the “past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” And if so, they did things worse than today. Life around the world today is more peaceful and prosperous than it has ever been and the list that follows tries to capture this reality by highlighting genuine achievements that might be lost amidst all of the doom and gloom that currently prevails. As such, it is a form of counter-programming to the nightly news.This commentary is not blind to certain realities. But it challenges their breathless, exaggerated presentation on the evening news.

As Swiss-born writer Rolf Dobelli notes, commercial newscasts affect the brain as sugar affects the body — “they are delicious, digestible and ultimately highly damaging.” Our brains, he writes, disproportionately respond to “scandalous, shocking, personalized, loud, quickly changing stimuli” and demur when confronted with information that is “abstract, complex and deserving of interpretation.”

Worse, when we are consistently confronted with one kind of information — and only one — we are increasingly likely to believe that information at the expense of any other kind. We tend, as Dobelli writes, to confirm our own biases. Or as U.S. philosopher-historian-linguist Noam Chomsky might say, we can choose to live in a world of comforting illusions. The more general our illusions, the more comforting and comfortable they become.

That is not to say that the current complexity of the world is merely in our heads. It has become more difficult to make sense of the world. During the Cold War, the ideological frontlines were simple, straightforward. No such obvious certainties exist today. As the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard said, the “grand narrative has lost its credibility.” Yet understandably, people still yearn for it. But if the world is more complex, it is also improving, as the list below shows.

True, the gap between the descriptive and normative remains appreciable. In 2000, when the United Nations adopted its Millennium Development Goals targeting eight areas — poverty, education, gender equality, child mortality, maternal health, disease, environment and global partnership, “they seemed Utopian,” The Economist noted. More than 15 years later, it might be hard to completely disagree, as only about half of the goals have been met.

Yet would anyone openly dare to dismiss those huge achievements and so many others of recent decades? As Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker writes, the current prevailing gloom is partly “the result of market forces in the punditry business, which (favour) the Cassandras over the Pollyannas.” Partly, it arises, says Pinker, from human temperament, quoting 18th-Century philosopher David Hume. The latter observes that the “humour of blaming the present, and admiring the past, is strongly rooted in human nature, and has an influence, even on persons endowed with the profoundest judgment and most extensive learning.”

But mainly, Pinker argues, it is the effect of a journalistic and intellectual culture that revels in sensationalism. Hamlet, as it turns out, had reasons to be resentful. But Hamlet’s fate also teaches us that apparitions can easily lead to self-destruction. Hamlet believed the ghastly images of his dead father to be real. We should know better than to believe in conjured up ghosts.

1. Decline in global poverty

It is not easy to count the global poor. Definitions of poverty vary among and across societies.

A leading definition by British sociologist Seebohm Rowntree describes poverty as the state in which “total earnings are insufficient to obtain the minimum necessaries for the maintenance of merely physical efficiency.” But this absolute definition of poverty fails to capture what sociology calls relative poverty.

As British sociologist Peter Townsend argued, every society enjoys an average bundle of resources that consists of certain activities, amenities and conditions. “Poor” people accordingly lack these resources. Different societies, in turn, value different bundles. While indoor plumbing might be a measure of affluence in many corners of the developing world, people in the developed world take it for granted and treat its absence as a sign of poverty.

All this said, several (but hardly all) metrics point towards a decline in global poverty, admittedly with uneven progress.

According to the World Bank, 1.9 billion people (or 37.1 per cent of the global population) lived on less than $1.90 a day in 1990. In 2015, it was 702 million (or 9.6 per cent), a drop of 74.1 per cent over 25 years.

The final United Nations report on the Millennium Development Goals finds similar figures. Whereas nearly half of the population in the developing world lived on less than $1.25 a day, that share dropped to 14 per cent in 2015. Globally, the number of people living in extreme poverty (as the UN defines it) has declined from 1.9 billion in 1990 to 836 million in 2010. According to the report, most of the progress occurred since 2000.

So what accounts for this decline? The World Bank says world trade is to thank, a point The Economist echoed in its Oct. 1 issue, in which it reported that “(export)-led growth and foreign investment have dragged hundreds of millions out of poverty in China, and transformed economies from Ireland to South Korea.”

Millions of people around the world, led by academic critics and by such non-academic critics as Canadian Naomi Klein, have challenged these claims in citing globalization as a source of economic dislocation and decline in developed and developing nations.

This space lacks the scope to settle this dispute. But if supporters of globalization acknowledge its deficiencies, critics also implicitly recognize its positive effects when they acknowledge the emergence of sophisticated consumer societies in Asia and elsewhere that rival, even exceed, their western counterparts in some areas, such as transportation and digital access.

2. War-related deaths drop

As of this writing, the estimated death toll from the Syrian Civil War approaches half a million. Millions more have fled the war-torn country for Europe and beyond in stoking the worst refugee crisis in human history. And many of those who remain now live among the ruins of cities such as Aleppo, a synonym for unbridled savagery in the pursuit of geopolitical gains, and a continuum of local and foreign powers, both large and small, show no sign of ceasing their struggle.

This carnage and confusion, amplified through continuous, occasionally cynical media coverage, have created the impression of a world that is descending into a murderous maelstrom of chaos and conflict. Yet what Joshua Goldstein, professor emeritus of international relations at American University, and Pinker, have called the “bloodiest conflict in a generation” actually appears as an aberration in what has been a steady decline in the number of war-related deaths.

As Goldstein and Pinker write in The Boston Globe, “for nearly two-thirds of a century, from 1945 to 2011, war has been in an overall decline.” During this period, the global death rate from war had fallen from 22 per 100,000 to 0.3 per 100,000. Yes, we have since seen this rate rise to 1.4 in 2014, according to Ali Wyne of the Atlantic Council. Yet this figure is “far lower than the average that prevailed in the Cold War,” a period that Wyne says witnessed “numerous civil wars and genocides, and the nuclear sword of Damocles came close to dropping on many occasions.”

While these facts might be cold comfort to the people in places across the Middle East and elsewhere, they remind us that human existence itself has become more peaceful. Pinker makes this point in his ground-breaking 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, in which he writes that “though it may be hard for news readers to believe, since the Cold War of 1989, organized conflicts of all kinds — civil wars, genocides, repression by autocratic governments, and terrorist attacks — have declined throughout the world.” This quantitative decline, which Pinker describes as the ”New Peace,” has “proceeded in fits and starts” and nobody would predict that it would be a long, never mind perpetual, peace. “There will certainly be wars and terrorist attacks in the decades to come,” he writes, “possibly large ones.”

Yet it would be equally “foolish to let our lurid imaginations determine our sense of the probabilities.” Writing in the New York Times with Colombian president and eventual Nobel Peace Prize winner Juan Manuel Santos in September, Pinker finds organized violence has become the almost exclusive domain of a zone that stretches from Nigeria to Pakistan, an area containing one sixth of the world’s population. “Far from being a world at war, as many people believe, we inhabit a world where five out of six people live in regions largely or entirely free of armed conflict.”

3. Fewer infectious disease deaths

Despite warnings about diseases such as Zika and Ebola, humans are living longer, healthier lives, as advances in medical science and governance push down death figures from infectious diseases. This point does not deny their past, present and potential effects on entire populations. Malaria, tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS remain “humanity’s deadliest foes,” as Nature reported in 2014.

This terrible trio continues to evade vaccine-finding efforts and collectively claims millions each year. HIV/AIDS alone was responsible for an estimated 1.1 million deaths in 2015, according to the United Nations’ anti-HIV agency, UNAIDS. HIV/AIDS has killed tens of millions since 1981 when health officials reported the first case and more than 36 million people currently live with the disease. And as David M. Morens and Anthony S. Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases write in The New England Journal of Medicine, infectious diseases remain a “perpetual challenge” whose “unpredictability” and “explosive global effects” have “influenced the course of wars, determined the fate of nations and empires, and affected the progress of civilizations.” Humans, in other words, “will always confront new or re-emerging infectious threats” that may turn entire societies upside down.

Yet, recent statistics also offer reason for genuine optimism. According to the World Health Organization, global deaths from malaria and TB respectively declined 48 per cent and 47 per cent between 2000 and 2015, with much of the drop occurring after 2000.

The news from the front in the fight against HIV/AIDS is also positive.

While the HIV/AIDS pandemic remains one of the most serious global health issues and the leading cause of death in Africa, many statistics point in the right direction. New infections dropped from 3.2 million in 2000 to 2.1 million in 2015, as prevention measures such as condoms gained popularity. HIV/AIDS-related deaths dropped from 1.5 million in 2000 to 1.1 million in 2015, a 36-per-cent decrease since the peak of 2005.

Increased availability of affordable antiretroviral drugs has been one reason for this decline in deaths. In 2000, fewer than a million people who carried HIV could access them. In 2015, the drugs were available to 17 million people.

Problems remain, however. While new infections have significantly declined since the 1990s, this decline has flattened out among adults over the last five years and the rate of new infections has been rising in some areas, including Russia. Its despotic government, which The Economist described as “immune to reason,” stigmatizes local sufferers, obstructs international agencies offering aid and indulges in dangerous conspiracy theories that dismiss HIV/AIDS as a hoax. Most people who live with the disease or risk contracting it, lack access to prevention, care and treatment. A cure, despite various pronouncements by prominent figures such as philanthropist Bill Gates, remains out of reach for the foreseeable future.

Yet, for all its grim aspects, the trajectory of HIV/AIDS is consistent with other trend lines that point towards a healthier future. The literature describes this development as the epidemiological transition. Christopher Dye, of the World Health Organization, says that it begins primarily with a fall in the death rate among children, thanks to vaccination and other efforts. (In the 1970s, fewer than five per cent of the world’s infants received basic lifesaving vaccines; now more than 80 per cent do).

“As a higher proportion of children survive to adulthood, parents choose to have smaller families,” Dye says. (Decline in fertility lags behind the decline in mortality). Over time, Dye notes, chronic, but non-infectious diseases common among adults begin to replace the infectious diseases common to childhood, with polio being the most prominent example.

This epidemiological transition, long ago completed in the developed world, is still unfolding in many parts of the developing world, perhaps too slowly for many. But to paraphrase an optimist, Martin Luther King Jr., the long arch of history is bending towards health.

4. Declining crime rates

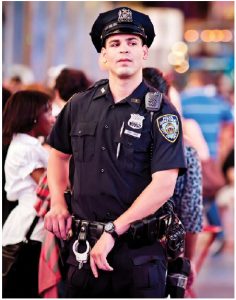

Statistics in the United States and elsewhere in the developed world show that violent crime rates have been plunging for decades.

Granted, media accounts suggest otherwise. Consider Chicago. According to The Chicago Tribune’s total for 2016, the city recorded 668 homicides by mid-November 2016. The figure for all of 2015 stood at 492. By August of 2015, the total number of people killed in Chicago, the third largest city in the United States, had exceeded the figures for the two larger cities — New York City and Los Angeles combined.

These trend lines have left the impression that crime is surging. Yes, projections for 2016 called for a 13.6-per-cent rise in the murder rate in the United States, with Chicago estimated to account for almost half of this spike. Overall, the murder rate in the United States has risen by a third since 2014, with Chicago, Baltimore and Houston accounting for most of this spike.

But once you zoom out of these hotspots, the larger picture is different. As the New York-based Brennan Center for Justice, a non-partisan think-tank, concluded in a report released in the fall of 2016, overall crime levels in the United States remain at “historic lows” with “reports of a national crime wave” explained as “premature and unfounded.” The average person “in a large urban area is safer walking on the street today than he or she would have been almost any time in the past 30 years,” the Brennan Center found.

Statistics from other sources underscore this point. Figures from the National Victimization Survey administered by the U.S. Justice Department recorded 18.6 incidents of violent crime per 1,000 people in 2015. In 1993, that figure stood at 79.8 incidents per 1,000 people.

Figures from Canada paint a similar picture. While police-reported crime rose 12 per cent in 2015 compared to 2014, this figure was 31 per cent lower than a decade earlier. Canadian crime rates had risen briefly, but from a low base, a point missed by headline writers who spoke of surging crime rates. In fact, this “surge” occurred just two years after police-reported crime had reached its lowest point since 1969.

Yes, some evidence suggests that this general decline might be heading in the opposite direction. But life — at least in the developed world — is very safe. So how can we explain the historical decline in crime?

Sociologists generally mention four factors: more police on the streets, aging societies, abortion (unwanted children are more prone to crime) and economic conditions. Notably, sociologists stress that higher incarceration rates and tougher prison sentences have generally failed to lower crime rates.

Pinker perhaps sums it up the best when he writes that the historical decline of crime rates has “had multiple causes, and no one can be certain what they were, because too many things had happened at once.”

That is not to say that crime — violent or otherwise — is becoming a thing of the past. Some experts have warned that the recent uptick in violent crime might signal a turning point. Technology-driven crimes, such as online fraud, hacking and other cyber crimes as well as sexual crimes, have also seen an increase, with the latter being the result of a changing culture and growing comfort among women to come forward.

5. Environmental progress

Recent reports about accelerating climate change and dwindling biodiversity make it all too easy to despair about the state of the natural environment and the eventual fate of humanity. Despair, however, is not a luxury in light of the stakes. And if action is the imperative of our age, we can look back upon a number of recent environmental improvements that may serve as inspiration.

The first is the state of the Earth’s ozone layer protecting planetary life from the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation emanating from the sun. Scientists, starting in the 1950s, found that the human production of chlorine-containing chemicals — chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — was thinning this protective layer.

Fears that ozone depletion could cause serious health and environmental harm eventually inspired the Montreal Protocol of 1987, which phased out CFCs following the discovery of a massive hole in the ozone layer above the Antarctic in 1985.

More than three decades later, these efforts have helped close the hole, according to research published in Science this summer.

“For years, [the Montreal Protocol] has slowed the rate of stratospheric ozone depletion,” and now there are signs that the ozone abundance over Antarctica has begun to increase.”

As lead researcher Susan Solomon, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), told the British media, “(we) can now be confident that the things we’ve done have put the planet on a path to heal.” But if Science expects the ozone layer to recover, this process will unfold “very slowly,” because CFCs can linger in the atmosphere for more than 50 years.

Also on the mend are a number of plant and animal species, thanks to tools such as the U.S.’s Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973. It has protected more than 1,300 plant and animal species and a recent study found that 99 per cent of protected species have avoided extinction. Robbins’ cinquefoil, a plant found in New Hampshire several years ago, became the first to be taken off the U.S.’s Endangered Species List. Also off the list are birds such as the American peregrine falcon and the American bald eagle.

The United States also recently removed most humpback whale populations from the endangered species list. “Today’s news is a true ecological success story,” Eileen Sobeck, assistant administrator for fisheries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, told the Guardian. “Whales, including the humpback, serve an important role in our marine environment.” Other whales are struggling. Consider the North Atlantic right whales and North Pacific right whales. Only several hundreds of each remain, according to the International Whaling Commission.

Biologists have also changed the status of the animal that has become the very symbol of various environmental conservation efforts — the giant panda. As of April 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) took the cuddly animal off the endangered species list.

Successful breeding and habitat conservation efforts under way since the mid-1980s have raised worldwide panda numbers to 1,864, a figure the World Wildlife Fund for Nature has called “hugely encouraging.”

Nevertheless, pandas, along with African elephants and polar bears, remain “vulnerable” and the IUCN has noted that climate change could destroy a third of the giant panda’s habitat, thereby undoing the diligent work of recent decades.

These improvements must also be considered within the context of the following prediction by the WWF: If current trends continue, two thirds of fish, birds, amphibians, reptiles and mammals will have disappeared in what would be the largest mass extinction event since the disappearance of the dinosaurs.

That said, the Montreal Protocol and the recovery of some species show what is possible.

6. Rising life expectancy

According to British medical journal The Lancet’s, global life expectancy at birth rose from 61.7 years in 1980 to 71.8 in 2015. The journal finds that, overall, life expectancy globally rose in 188 of 195 countries, and, in many, at faster than anticipated rates.

Let us now acknowledge a place where this trend is heading in the wrong direction: Syria. According to The Lancet, the average lifespan of a Syrian man dropped by 11.3 years to 62.6 years between 2005 and 2015, with war being the main cause for the decline.

Syrian infant mortality, not surprisingly, also rose by 9.3 per cent between 2010 and 2013. Overall, research by the journal reveals that the Syrian civil war has reduced Syrian life expectancy by three months each year. These numbers themselves represent a larger point: Death from interpersonal violence and war has risen across the Middle East between 2005 and 2015.

But if this fact confirms the negative perception of the region, it also obscures a larger point: The Middle East represents an exception to the rule of rising life expectancy across the globe, as described above.

So what accounts for these developments? We have already highlighted two reasons: The decline in war-related deaths in most corners of the world and what the report called “marked reductions” in mortality from HIV/AIDS, malaria and other infectious diseases through various improvements in immunization, sanitation and other factors. Children, not surprisingly, are those with the most gains in life expectancy. According to the study, 5.8 million children under the age of five died last year, a drop of 52 per cent since 1990.

But reasons for concern also exist. Deaths from non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and stroke, bear responsibility for seven out of 10 global deaths. According to the study in The Lancet, titled “Global Burden of Diseases,” rising rates of obesity, hypertension, alcohol and drug abuse threaten to overthrow much of the progress in recent decades.

Progress, in other words, has remained somewhat patchy and subject to reversal.

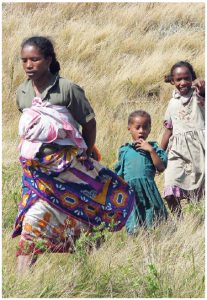

7. Maternal deaths decline

As previously mentioned, this list invites two possible interpretations. On one hand, it can be read as a reminder of progress. On the other hand, it also records failure by pointing to the problems that remain. This forces us to praise a concept of less failure, but it’s failure nonetheless, in fields where failure is deadly. Consider the global state of maternal health. The number of women who died from childbirth and pregnancy-related causes almost halved since 1990, according to a report by The Lancet, a British medical journal. It found that the worldwide annual number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births fell by 44 per cent between 1990 and 2015, from 385 to 216. Skilled health personnel assisted more than 74 per cent of all births in 2014, an increase from 57 per cent in 1990.

But what counts as progress also means that hundreds of thousands of women — most of them in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia — still die each year while being pregnant or giving birth. Almost 290,000 suffered such a fate in 2013, according to a United Nations estimate.

The ambiguity of this accounting also appears when we hold it up against the United Nations’ stated Millennium Development Goal of reducing the maternal mortality rate by two thirds, an ambition that has obviously gone unfufilled. Yet, it would be equally disingenuous to dismiss what has been achieved.

Today, millions are alive and would not be if governments, non-governmental organizations and others had not invested their money, emotions, efforts and energy.

One such notable actor was Canada under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, who was an instrumental figure behind the Muskoka Initiative. Named after the 2010 G8 meeting site where it was announced, it committed a total of $7.3 billion US of new and additional spending towards maternal, newborn and child health. Under the initiative, Canada committed $1.1 billion in new funding and agreed to maintain $1.75 billion in existing funding for a total contribution of $2.85 million over five years. As of 2015, Canada had disbursed more than 97 per cent of that funding.

More work needs to be done. Access to maternal health remains uneven and varies according to the wealth of a region. Whereas women living in high-income countries face a 1-in-4,900 chance of dying during child birth, these odds worsen to 1 in 36 for women in sub-Saharan Africa. Wendy Graham of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who co-ordinated the report, said it best in her remarks to The Guardian: “Lots of people worked very hard and progress was achieved. Like many things in health, in the progress that the average [person] receives, invariably there are some left behind.”

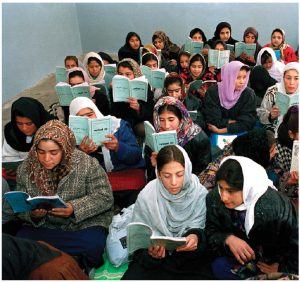

8. Rising literacy rates

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are dead, long live the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Announced in 2015, the SDGs set out to shape global development until 2030 by following in the footsteps of the MDGs. But if the MDGs came across as a relatively concise catalogue of eight goals, the SDGs sprawl across 17 primary targets and 169 associated targets.

“Moses brought 10 commandments down from Mount Sinai. If only the UN’s proposed list of Sustainable Developments Goals were as concise,” The Economist wryly observed months after their passage. This goal inflation has accordingly invited questions about their overall achievability. Yet beneath all of their bloat, the SDGs highlight what analysts from various academic corners have long recommended.

Consider the following: According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the global literacy rates for youth (aged 15 to 24) increased from 83 to 91 per cent over 20 years. The number of illiterate youth declined from 170 million to 115 million. While it might be difficult to discern the immediate effects of these efforts, studies show that literacy is one of the strongest drivers of economic progress, prosperity and environmental protection.

As a 2013 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report notes, “educated people are more likely to understand, support and create solutions that ensure the development of sustainable cities and communities, as well as to use energy and water more efficiently and recycle household waste.”

UNESCO further says studies have identified increased literacy through education as “an essential foundation of peace, tolerance and a healthy civil society.”

Literacy also raises the social status of women. Various scholars, including American philosopher Martha Nussbaum, have identified literacy as a tool in the quest for political emancipation.

As always, these improvements vary across regions. While UNESCO reports that 60 per cent of all countries and areas with available data have eradicated youth illiteracy, literacy rates in several West and Central African countries remain at less than 50 per cent.

9. More women in business

Female entrepreneurs to the rescue. That could be the headline over a growing body of evidence that shows that female business leaders are playing an increasingly more important role in the fate of their respective societies and the global economy at large. Let us first acknowledge that the rate of entrepreneurship among women is lower than among men for reasons that sound entirely familiar. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, women face more “social and cultural constraints” than men. Such obstacles include higher levels of domestic responsibility, lower levels of education, a lack of female role models, fewer business networks in their communities, a lack of capital and assets, lower status in society and a culturally instilled lack of assertiveness and confidence in their abilities to succeed in business. “These factors may prevent women from perceiving, as well as acting on, entrepreneurial opportunities,” write the authors of Women’s Entrepreneurship, published by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GME), which studies the nature of entrepreneurship. Surveying 83 economies, the authors find a wide range of what they call early stage entrepreneurship activity (TEA) rate, a percentage that measures the portion of the adult population (18 to 64 years) that plans to or has recently started a business.

According to this research, female entrepreneurship rates range from a high of 41 per cent in Nigeria and Zambia to a low of 2 per cent in Suriname and Japan. In 10 economies, women are as likely as men, or more likely than men, to be entrepreneurs. Overall, female entrepreneurship rates have increased by 7 per cent since 2012 among 61 out of 83 surveyed economies, a desirable development.

As the World Bank shows, female entrepreneurs contribute substantially to economic growth and poverty reduction around the world. Research from the Kauffmann Foundation also shows that businesses with female executives take a more nuanced view of risk, are more creative and have a higher likelihood of success. Or put another way, businesses need women to succeed and the economy needs women, especially in the developing world, where female participation helps ease poverty. This reality, in turn, points towards a broader point: inclusive societies are productive societies.

10. More female politicians

The highest and hardest glass ceiling remains unbroken. But if the failure of Democrat Hillary Clinton to win the presidency of the United States against Donald J. Trump might depress some, it should not obscure the fact that the number of female politicians is rising. Consider the following numbers, as compiled by the Geneva-based Inter-Parliamentary Union.

In January 1997, women made up 11.7 per cent of all elected representatives. Fast forward to September 2016, when the overall proportion had risen to 22.8 per cent. However, these gains appear more impressive once we look at the regional figures. For example, women made up only 3.3 per cent of political representatives in the Arab world in 1997; their institutional presence had risen to 17.6 per cent by September 2016.

Other areas without any long record of female representation have also recorded gains. From January 1997 to September 2016, female representation rates in sub-Saharan Africa rose from 10.4 to 23.1 per cent. In the Pacific region, which includes Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Samoa and neighbouring islands, it rose from 11.6 to 16.3 per cent, and in Asia, from 13.1 to 19.2 per cent.

These continental figures do not capture country-by-country variations, with some countries reporting figures far above the average. Consider Rwanda, where women hold about 64 per cent of all parliamentary seats, the highest rate in Africa and the world, according to the United Nations.

Turning to the Americas and Europe, rates there are also rising. In the Americas, women held about 27 per cent of parliamentary positions in September 2016, up from 12.7 per cent in January 1997. As for Europe, women held 11.5 per cent of all parliamentary seats in January 1997. By September 2016, the number had risen to 24.5 per cent.

Female politicians have also played an important role in the Nordic countries. In January 1997, 36 per cent of all parliamentarians were women. In September 2016, that number stood at 41.6 per cent. A woman — Erna Solberg — also currently governs Norway as prime minister, and all Nordic countries, except for Sweden, have already had at least one female leader.

The growing institutional presence of women in European politics also appears in other ways. Women govern Europe’s second most populous country (Germany, 81.4 million) and fifth-most populous country (United Kingdom, 65.1 million). In fact, it would not be a stretch to argue that Angela Merkel and Theresa May are the two most powerful women on the planet. Other powerful female leaders include Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund, and her fellow French citizen, Marine Le Pen, of France’s Front National, who may yet win the French presidency in the spring of 2017. In addition, Taiwan just elected its first female president, Tsai Ing-wen.

And we mustn’t forget Nicola Sturgeon of the Scottish National Party. She currently serves as Scotland’s first minister and may eventually become the first head of an independent Scotland. Finally, Sheikh Hasina Wajed, responsible for the governance of 160 million people, is leading Bangladesh for the second time.

Overall, more than 70 nations have already had a female leader, according to the New York Times. So while the world’s most powerful state still awaits its first female leader, glass ceilings elsewhere have already shattered.

Wolfgang Depner has taught political theory and international politics at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus. He now lives in Victoria.