In the beginning, Madagascar was physically part of Africa, as were the islands of Seychelles, Mauritius and the Comoros. Some 165 million years ago, a cataclysmic earthquake set Madagascar free on a 45-million-year 400-kilometre northeastern journey to its current location.

For millions of years, Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world, has been teeming with an abundance of exotic wildlife, from wide-eyed monkey-like lemurs, giant tortoises, hundreds of species of reptiles and dozens of bats to rabbit-like jumping rats, colourful birds and so many more unique creatures.

Recent archeological surveys reveal settlements dating back more than 4,000 years, but the general consensus is that seafarers from Borneo and Austronesia were the first true settlers on the island between AD 100 and 500, and that today’s population is descended from Indonesian and Malay migrants. The seafarers arrived in outrigger canoes laden with food staples from their homelands, including rice, plantain, taro, water yams and probably sugarcane, ginger, coconut, bananas, pigs and chickens. Immediately, they established a “slash-and-burn” type of agriculture, clearing virgin rainforests to grow crops. To supplement their domestic food supplies, they also became gatherers (honey, wild fruits, edible seeds and nuts, mushrooms, crocodile and bird eggs) and hunters (birds, lemurs, wild boar, hedgehogs, tortoises, frogs, snakes, lizards, insects and larvae). These early settlers probably indulged in the eggs and the meat of aepyornis maximus (the elephant bird), the world’s largest bird, which continued to survive in large numbers across the island until the 17th Century.

Unfortunately, the hunting of game, together with the slash and burn agricultural practices, eventually led to the extinction of almost two dozen of the original irreplaceable species, including dwarf hippos and giant lemurs. Despite the fact that hunting lemur has been illegal since 1964, the practice continues for personal consumption in rural areas and to meet the demand for exotic bush meat from some urban restaurants.

Immigrants add their cuisine

Around AD 1000, East African migrants brought with them a type of humped-back cattle known as zebu, plus other new sources of food that included sorghum, bambara groundnuts and goats. Recognized as symbols of wealth, cattle were rarely eaten except after being sacrificed at important spiritual events such as funerals. Rather, fresh zebu milk and curds made up a principal part of the pastoralists’ diets. Some zebu escaped from their herds and established themselves in the highlands where inhabitants believed them to be inedible until the 16th Century when King Ralambo, ruler of the central highland kingdom of Merina, declared the cattle could be eaten.

Stories of King Ralambo, auspiciously born on the first day of the new year, portray him as a near-mythical hero for his great military victories plus significant and enduring political and cultural contributions, including to food culture. He popularized the consumption of meat and celebrated it by establishing a New Year’s festival. This festival involved an ancient ceremony called the Fandroana (the Royal Bath) where beef confit, or jaka, was prepared by putting beef in a decorative clay jar sealed with suet and storing it for a year in a subterranean pit where it was later shared with fellow royals and subjects.

For dessert, festival-goers enjoyed rice boiled in milk with a honey drizzle. As time when on, traditional foods were enhanced and became the seven royal dishes, known as hanim-pitolha, and the basis of what is regarded today as Malagasy cuisine. Indeed, food played an important role in Madagascar’s culture. Previously, Ralambo’s father had introduced the marriage tradition of “rump of the sheep,” wherein the groom presented his future bride’s parents with the hindquarters of a sheep — the most desirable part of the animal — at the engagement ceremony. Madagascar Ambassador Constant Horace confirms that such a tradition prevails in Malagasy society, but symbolic coins are usually substituted for the meat, except in some rural areas that remain true to tradition.

Trade with Arab and Indian merchants resulted in migrants who further enriched Madagascar’s culinary traditions coming from those areas. And even though the inhabitants lived in tribes, the Africans, Indians and Arabs were assimilated into the Malagasy-speaking society, thus avoiding segregation. The first Europeans to land in Madagascar were Portuguese explorers in 1500. News of their discovery resulted in several attempts by the French and British to establish settlements. These proved unsuccessful due to disease and local hostility.

The 17th Century saw the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade, which intensified maritime trade with Malagasy ports, initiating a “domino-effect” that brought new food products and agricultural practices to Madagascar. The new food and practices were quickly adopted by locals and incorporated into the country’s food culture. By that time, terraced, irrigated rice paddies had become so productive, not only could they fulfil islanders’ needs as a primary food crop, but they also, apparently, became an export commodity. Trading ships took Malagasy rice to Charleston, S.C., forming the basis for plantation rice production there.

Trading ships travelling back from South Carolina, brought sweet potatoes, corn, tomatoes, lima beans and peanuts to Madagascar. Islanders soon began cultivating these products themselves — first in coastal regions adjacent to ports of arrival. From there, they spread throughout the country. With sailors’ need to ward off scurvy during long voyages, the introduction and cultivation of citrus fruits (oranges, lemons and limes) quickly followed.

The New World’s prickly pear cactus — known as sakafon-drano or “water food” — rapidly became an essential crop across the semi-arid southern region, where consuming six pieces of fruit per day eliminated a pastoralist’s need for drinking water. Further, their cattle were nourished and hydrated by the stems. In fact, the prickly pear cactus allowed these farmers to become better herdsmen with much bigger herds.

The 19th Century witnessed a dramatic evolution in Malagasy cuisine — Madagascar farmers started importing and then planting cloves, as well as coconuts and vanilla. Ambassador Horace points out that today, Madagascar produces 75 per cent of the world supply of vanilla.

More newcomers added other dimensions to the culinary mix. The first major influx of Chinese migrants, responding to requests for workers to build a northern railway, introduced their own specialties, including fried rice, fried noodles, noodle soup and egg rolls. Heading into the 20th Century, an original community of 200 Indian traders who had established a port on the northwestern coast, expanded to 4,000 within only three decades and popularized curries and rice-based biryanis in addition to the street food, such as Indian samosas, throughout the region. With French colonial rule beginning in 1896, well-embraced French baguettes, pastries and desserts as well as fois gras and cold macaroni salad mixed with blanched vegetables came along. French also became the country’s official language. Madagascar didn’t achieve independence until 1960.

Traditional Madagascar food

In Madagascar, food has always been cooked using simple methods and techniques, such as roasting over a fire, grilling over hot stones or coals and boiling, first in containers made of green bamboo, then in clay pots and metal vessels. Food preservation techniques included smoking, sun-drying and salting. Smoked dried beef, known as kitoza, salted dried fish and many other foods are still prepared in a similar manner today. The process of fermentation was adopted early in the history of Malagasy cuisine to produce curds from milk, to amplify the flavours of particular fresh and dried tubers and to make alcoholic drinks.

The food of Madagascar is charming in its simplicity. A traditional Malagasy dish features an unusually large amount of rice — the cornerstone of Malagasy cuisine — accompanied by a modest portion of chicken or fish, usually in a sauce, and vegetables. Some claim they face a sleepless night if they have not had rice at least once a day. Rice’s prevalence remains in contemporary cuisine across the entire island; however, farmers in the arid south and west often substitute corn, cassava or curds made from fermented zebu milk for the rice. A bowl of only rice is considered a very acceptable meal. Red rice for breakfast is ubiquitous throughout the country, often made with extra water, producing a soupy rice porridge, known as sosoa. The latter is sometimes eaten with kitoza (smoked strips of zebu meat). A traditional porridge, vary aminanana, includes white rice, meat and chopped greens.

As for meat, the principal source remains zebu cattle. The Malagasy people enjoy better cuts served as zebu steaks or zebu stew, while less tender pieces, cut into small cubes, are boiled until very tender in salted water along with garlic and onions, shredded and finally roasted. Islanders also consume chicken (frequently in a curry) and goat; but pork, although available, is taboo in many areas of the country. Vegetables are served simply boiled or with spices to boost flavour. The other primary element of a traditional Malagasy dish, the sauce, derives its flavours from onion, garlic, tomato, ginger, curry, vanilla, coconut and, at times, herbs and spices. Sauces vary by region. Generally, one finds tomato-based sauces in the highlands and coconut-based sauces on the coasts.

Flavourings of dishes also vary by region. Coconut-based seafood and crustaceans appear on the northeast coast; thyme, basil and lemongrass-scented dishes in the central plateaus; clove, pepper, cinnamon, ginger and lemongrass-infused recipes in the eastern part of the island; kaffir lime and lemon-flavoured specialties in the drier western areas and into the south; and dishes infused with aromatic plants in the north along the Antsiranh and Amber mountain ranges. The term bredes refers to particular plants and vegetables that are classified in two categories defined by flavour — mamy bredes are mild leaves while anamolaho are spicy; however, the food of Madagascar exhibits delicious tastiness without being hot and spicy. Those preferring extra zip in their rice or accompaniments cautiously add touches of chili relish (satay) that comes in strengths from hot to fiery spicy, or spicy mango, vinegar-preserved carrots, lemon pickles or hot curry oil. These condiments are served on the side to be incorporated according to personal taste.

Other specialties

Ro, a Malagasy traditional dish, is typically a broth-based soup cooked with leafy vegetables. It may be served as an accompaniment or to add flavour and moisten rice. Many variations exist, including the inclusion of chicken and ginger, shrimp and beef, but romazava consists of a broth with zebu beef, bredes, including anamaloa flowers, and other ingredients, such as onion, tomato and ginger, to boost the complexity of flavours. Along with ro, Malagasy folks enjoy ravitoto, a rice-based dish with beef or pork, ground or shredded cassava leaves and, at times, with coconut milk served on the side. They also like other traditional meat dishes: varanga, which is beef simmered, shredded and braised with onions; vorivorin-kena, which is beef tripe; khimo, a curried ground beef; and hena kisoasy voanjubory, which is pork with cape peas.

Fish and crustaceans thrive in coastal waters. Coral reefs swarm with crab, octopus and squid, while mangroves harbour oysters and giant shrimp. Among the specialties would be tilapia, fried in oil with garlic; rock lobster, boiled, combined with a sauce of tomato, shallots, garlic, ginger and cloves and served with rice cooked in coconut oil; and amalona, an eel split lengthwise, stuffed with pork, garlic, ginger and onion, and then sewn closed.

Ambassador Horace confirms that traditionally, food is served steaming hot, adding that “cold food lacks popularity.”

Contemporary cuisine

Today, Malagasy cuisine more robustly blends the influences of many culinary traditions, including those brought by migrants from Southeast Asia, Africa, the Arab world, India, China and Europe. These migrants arrived in Madagascar after it was first inhabited by early seafarers from Borneo and Austronesia.

Outside the home, traditional Malagasy cuisine is available at eateries and roadside stands, while upscale restaurant menus offer a wider variety of foreign dishes and traditional specialties, influenced by foreign preparation techniques, ingredients and presentations. Street food is popular and can include samosas, spring rolls, brochettes, grilled or steamed cassava, sweet potatoes, rice cakes known as mofo gasy; steamed cakes with ground peanuts, mashed bananas, honey in brown sugar wrapped in banana leaves known as koba; deep-fried wonton-type strings of dough called kakapizon and yogurts.

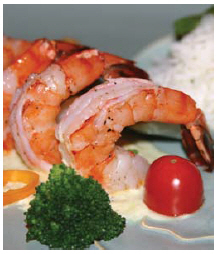

Please enjoy my version of Madagascar Shrimp with Island Spiced Sauce. Mazotoa Homana! Bon Appétit!

Madagascar Shrimp with Island Spiced Sauce

Makes 4 servings

1 lb (450 g) very large shrimp, not peeled (count: 16 to 20 per lb)

1 tbsp (15 mL) coconut oil*

To taste, salt and crushed black peppercorns

To taste, fresh cilantro

Island Spiced Sauce

1 stalk fresh lemongrass

1 tsp (5 mL) chicken bouillon powder

3/4 cup (180 mL) hot water

2 tsp (10 mL) coconut oil*

½ tsp (3 mL) minced fresh garlic

1/3 tsp (2 mL) peeled and grated fresh gingerroot

2 tbsp (30 mL) Pernod

3 oz (85 g) soft unripened goat cheese

1/3 tsp (2 mL) curry powder

1. Peel shrimp, leaving tails attached and set aside.

2. To make the Island Spiced Sauce, remove the tough outer layers of the lemongrass, cut 3 inches (7.5 cm) off the bottom of the stalk, split it vertically into long slices before pounding to release flavours. (Discard the rest.)

3. In a small saucepan, dissolve instant chicken bouillon powder in hot water, add lemongrass and allow to simmer until reduced to ½ cup (125 mL). Remove from heat, strain through a sieve and discard lemongrass.

4. In a small cast-iron skillet over medium-low heat, heat 2 tsp (10 mL) of coconut oil. Add garlic and ginger; sauté for less than one minute, stirring constantly.

5. Add Pernod, then the goat cheese and chicken bouillon mixture, stirring constantly until sauce comes to a boil. Reduce heat to a gentle simmer.

6. Add curry powder and continue stirring constantly, until the sauce is thick enough to coat the back of a spoon (i.e., reduced to 3/4 cup or 180 mL).

7. Heat 1 tbsp (15 mL) of coconut oil in a large non-stick skillet over medium-low heat. Sauté shrimp briefly on both sides, seasoning with salt and crushed black peppercorns, just until pink with centres barely approaching opaque.

8. Serve shrimp immediately on a smear of Island Spiced Sauce and garnish with fresh cilantro leaves. Serve with rice and vegetables of choice.

* Note: There are two additions of coconut oil.

Margaret Dickenson is a cookbook

author, TV host, menu/recipe developer, protocol, business and etiquette instructor. (www.margaretstable.ca)