In the run-up to the French election following Britain’s decision to leave the European Union, there were dire predictions about Europe’s future. France’s mainstream parties struggled to find their footing and Marine Le Pen, the right-wing, anti-Europe, anti-immigration candidate, gained traction with French voters who had grown increasingly disgusted with the status quo and yearned for a future that would take the Fifth Republic back to happier days.

Globalization and Europe’s institutions were under attack by the new forces of populism. Even Canada was not immune to the anti-Europe, anti-free trade tide. The ratification of the Canada-European Union (EU) Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement was temporarily held hostage by the Belgian regional parliament in Wallonia, which refused to give its consent to the deal unless certain demands were met. (Eventually, it did consent, after a compromise was struck.)

Europe’s struggling economy and ballooning public deficits added to the strong sense of gloom. Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s own highly sophisticated propaganda war in the run-up to the French election, which was being launched over Russia Television (RT), social media and through various surreptitious cyberattacks against well-known politicians, reinforced the sense that Europe was a mess and ripe for Putin’s manipulations. So, too, did Donald Trump’s initial pre-U.S. election message that the NATO Alliance was obsolete and Europe should look after its own defence instead of bilking the American taxpayer.

The influx of refugees into Europe from the Middle East and North Africa beginning in 2011 also whipped up the anti-immigration, anti-globalization populist frenzy, putting mainstream politicians on the defensive. Even German Chancellor Angela Merkel was left temporarily speechless by a young Palestinian girl who burst into tears after the chancellor announced that Germany “just can’t manage” to take every refugee — this after Germany had opened its doors to more than a million.

Many pundits feared that Europe’s new populist wave would scuttle the vision of Europe’s founders, Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet and Konrad Adenauer, of a united, free, prosperous Europe without borders.

The election of centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron as France’s new president, which followed the re-election earlier this year of Mark Rutte’s centre-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy in the Netherlands, has somewhat eased fears that Europe is about to lurch to the far right and tear itself apart as ultra-nationalists grab the reins of power (notwithstanding Britain’s impending departure from the European Union on terms that have yet to be negotiated). So too has the British election, which has crippled Prime Minister Theresa May governing Conservative party, reducing the likelihood that Britain will negotiate a “hard” exit from the European Union.

Macron, who is often compared to Napoleon Bonaparte and former U.S. president John F. Kennedy, is the youngest democratically elected leader to win the French presidency. He did not carry the political baggage of the other candidates on the right or the left as a relative newbie to the French political scene. And he is now seen as the new keeper of the flame for globalization, free markets, and European solidarity.

The distinguished French political scientist and public commentator Dominique Moisi of the Institut Montaigne in Paris writes: “Macron’s wife jokes that he takes himself for Joan of Arc, the French peasant who saved the country from the British in the Middle Ages. Physically, Macron evokes more the young general, Napoleon Bonaparte, during his first campaign in Italy. Some see in Macron a romantic figure straight out of a Stendhal novel, a modern Fabrice del Dongo, who decides not to be a mere spectator of the world, but to act on it. He advances his mission through a combination of youthful energy, self-confidence, political cunning, technocratic competence and a sense of moderation. Macron embodies a sea change in French electoral politics: the erosion of the traditional cleavage between right and left.”

A self-described centrist after he left the Socialist Party, Macron founded his own political party, En Marche! He had previously held the post of economic minister in François Hollande’s socialist-led government. Macron and Hollande parted ways after Macron decided that Hollande would not administer the kind of tough fiscal medicine that he (Macron) had recommended to revive the French economy.

Macron is resolutely pro-European and is proposing, in his words, “to restore the credibility of France in the eyes of Germany, [and] to convince Berlin in the next six months to adopt an active investment policy and move towards greater solidarity in Europe.” As a former businessman, he also wants to make France more competitive. He has promised to lower corporate taxes from the current rate of 33 per cent to 25 per cent. He also wants to keep France’s generous 35-hour work week rules in place, but leave negotiations to companies about actual work hours of employees. Welfare benefits for low-wage earners will also be cut. Additionally, Macron has promised to cut the public-sector payroll by 100,000 employees, which will almost certainly put him on a collision course with France’s powerful public sector unions. At the same time, he wants to spend $66 billion in public investments over the next five years to rebuild France’s infrastructure.

Macron will certainly have his work cut out for him though he is off to good a start by securing a majority for his own party in the French legislature. He now has the political heft to push through his controversial economic and labour reforms package. Only time will tell though if France’s powerful public sector unions who are deeply attached to the French welfare state will push back.

The bigger question is whether Macron’s election in continental Europe’s second-biggest economy signal that the populist anti-globalization tide is over as voters take a cold, hard look at their pocketbooks? Like the tide, it is going out, at least for now, but like the tide, it can come roaring back in if there is not a fundamental recalibration of economic policy not just in France, but also other EU countries, including Germany.

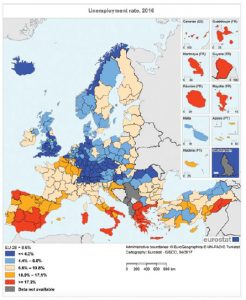

The good news is that the economy of the European Union is slowly crawling out of the doldrums of the past decade as consumer confidence recovers and the extraordinary monetary policies of the European Central Bank, which have involved large-scale quantitative easing and major asset purchases, continue to keep interest rates and inflation low. EU forecasts show that the economies of all member states will continue to grow over the next two years (1.6 per cent in 2017 and 1.8 per cent in 2018). Unemployment rates will also fall, though they remain well above the pre-crisis levels of the previous decade. The black mark on recovery is investment, which, in the polite words of European officials, “remains subdued.” Much of the EU’s growth forecast is predicated on strong economic recovery in the United States (which now seems to be in jeopardy as the presidency of Donald Trump stumbles and confidence in the U.S. economy tumbles) and growth in emerging economies, where a rapidly growing middle class will almost surely be the engine of global economic expansion.

Large-scale infrastructure projects, financed under the investment plan for Europe, will also temporarily boost growth and employment after they are approved and implemented. As the European Commission notes, “Overall, investment in the euro area is forecast to grow by 2.9 per cent this year and by 3.4 per cent in 2018 (2.9 per cent and 3.1 per cent in the EU), up 8.2 per cent by now since the start of the recovery in early 2013. However, the share of investment in GDP remains below its value at the turn of the century (20 per cent in 2016 compared to 22 per cent in 2000-2005). This persistent weakness in investment casts doubt over the sustainability of the recovery and of the economy’s potential growth.” And there is the rub: Without substantial levels of sustained investment, there will not be sustained growth.

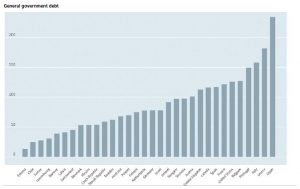

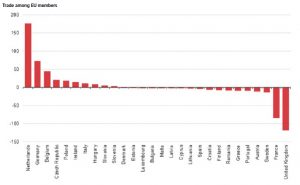

But Europe’s challenges run much deeper than simply a shortage of investment. There are major structural imbalances at the regional and national levels that continue to hang over Europe’s future like an albatross. The first is Germany’s rigid adherence to a policy of balanced budgets and export-led growth, much of it to the weaker Mediterranean economies of the Eurozone, which have been able to live beyond their means since the adoption of the euro. Until Germans start to spend more, save less and import more in the way of goods and services from their European partners (who need to tighten their belts and get their own fiscal houses in order), the Union will be a marriage between the proverbial Jack Sprat (who could eat no fat — in this case fiscal “fat,” meaning Germany) and his wife (who could eat no lean — France, Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal). Only, in this case, unlike the Mother Goose nursery rhyme, the moral of the story — that it is better to go to bed without supper than to rise in debt — has been lost on the Mediterranean members of the Eurozone.

France itself is a textbook example of the problem. France lags well behind the Eurozone growth rate of 1.6 per cent. Since 2013, the French economy has only grown at an average annual rate of one per cent. Per capita incomes have been stagnant and are now falling, which is one of the reasons for the strong support given to populists such as Marine Le Pen. Worse, the French economy’s ability to withstand future economic shocks or disruptions will be quite limited because of its anemic state. Worse still, public expenditures account for roughly 60 per cent of France’s overall gross domestic product. The level of public debt rivals the country’s overall GDP at almost 100 per cent. Unemployment is staggeringly high with youth unemployment topping 25 per cent. French productivity, which is surprisingly above U.S. levels and has been so for quite some time, is now falling.

Italy, the continent’s third-biggest economy, faces similar problems and, unlike France, does not enjoy the kind of strong, decisive political leadership that — at least for now — Macron promises to bring to the French people. If Macron fails, Le Pen and the populist, nationalist tide that briefly floated her political fortunes will rise again and Europe’s future will be cast in doubt.

Fen Osler Hampson is director of the World Refugee Council. He is also a distinguished fellow and director of the Global Security & Politics Program at the Centre for International Governance Innovation. He’s also Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University.