Summer is upon us and it is time to choose an adventure. It is this imperative that has guided our decision to compile this list of adventure tourism activities that offer us thrills beyond the ordinary. The Adventure Travel Trade Association defines adventure tourism as a trip that includes at least two of the following: physical activity, natural environment and cultural immersion.

“While the definition of adventure tourism only requires two of these components, trips incorporating all three tend to afford tourists the fullest adventure travel experience,” says the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the United Nations agency responsible for the promotion of responsible, sustainable and universally accessible tourism.

With that criteria at the forefront, we’ve chosen 15 adventure activities, spread across three categories: air, water and land. While this list is admittedly subjective, it considered a number of criteria, including region and accessibility, in drawing inspiration from a wide range of sources and communities, including the extreme tourism community (see the entry on animal-watching in Chernobyl) and hardcore adventurers such as those behind the Grand Inga Project, a hair-raising descent down the Inga Rapids on the Congo River. While such death-defying feats remain beyond the reach of most, they nonetheless draw attention to what is possible. According to the UNWTO, adventure tourism is on the rise as one of the fastest-growing categories of tourism. It is at once more sustainable, resilient and supportive of local economies than mass-packaged tourism. Plus, it promises far more memorable interactions with locals and their environment than sitting around a pool. With this in mind, safe travels. See you out there.

1. Paragliding, Haute Alpes, France

More than 300 days of sunshine, strong thermal winds and spectacular scenery — those are the elements that make the French Haute Alpes perhaps the global destination for paragliding. In this aviation sport, wind inflates a canopy that the pilot controls by tugging the cords that tether a harness to the canopy. While harnesses — which resemble high-end lawn chairs — vary in weight, they are much lighter than other types of glider aircrafts launched by foot. This portability means that paragliding pilots can launch themselves and their passengers off any sufficiently steep slope free of obstructions that face the wind. Gravity and wind do the rest.

Skilled paragliding pilots can stay in the air for hours, reaching heights in excess of 5,000 metres, while covering distances of more than 200 kilometres. But if paragliding can happen almost anywhere, why settle for anywhere when you can do it in the Alpine mountains of southeastern France on the borders of Switzerland and Italy? Accessed through Albertville, host city of the 1992 Winter Olympics, the region is home to the Mont Blanc massif, a mountain range that straddles France, Italy and Switzerland and bears the name of the tallest mountain (4,800 metres) in Europe.

Already famous for skiing during winter, the landscape is one of the reasons France boasts more than 25,000 active paragliding pilots. And as climate change slowly, but inexorably, closes down local ski runs, area resorts have sought to diversify their recreational offerings, including paragliding. Accordingly, visitors can choose from a broad range of suppliers that offer lessons, tandem flights or other related services.

To be clear: all air aviation sports can be dangerous if pursued carelessly. “The most important requirement for safe and successful paragliding is a proper attitude and good judgment,” said Kurt Kleiner of the U.S. Hang Gliding & Paragliding Association on its website. Those who follow this advice will be uplifted.

2. Hang-gliding, Fjord Region, Norway

For some, western Norway is a place of unparalleled beauty.

“It is an unusual expanse of landscape, not duplicated anywhere on Earth,” wrote famed New York Times columnist R. W. Apple Jr. during a road-trip through the region in 1980. “[Nowhere] else, in a relatively confined area, is there such a prodigal display of mountains and sea, lakes and waterfalls.”

The region’s fjords — spindly fingers of ocean reaching far inland — are the primary players in what Apple calls a “scenic melodrama.”

Areas of interest include the Geirangerfjord and Nærøyfjorden, which UNESCO has placed on its list of World Heritage Sites as archetypical examples of the west Norwegian fjord landscapes that stretch 500 kilometres, from Stavanger in the south to Andalsnes to the northeast. Historically, visitors have absorbed this scenery from land or from the deck of a ship.

These days, more and more are taking to the air, as the region has become a hotspot for hang-gliding. Basically, a pilot controls a triangular wing by shifting weight forward, backward and side to side inside a harness suspended off the wing. The history of hang-gliding reaches back to the Renaissance and emerged as a modern recreation sport in the 1960s. It has since become one of the most popular forms of foot-launched aviation.

Voss, a small community in western Norway, about an hour east of Bergen, Norway’s second-largest city, ranks at or near the very top of the destinations for the global hang-gliding community thanks to the glacier-covered mountains and deep fjords that surround it. Like so many Norwegian communities, Voss can look back on a rich, but often hard-scrabble, history that inspired many waves of migration. Today, Voss advertises itself to adrenaline junkies from around the world through its Ekstremsportveko, a week of extreme sports competitions.

3. Ballooning, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Popular culture does not always paint Albuquerque in the brightest hues.

For the cartoon rabbit Bugs Bunny, New Mexico’s largest city was always the place at which he should have taken a left. Others will forever associate this former Spanish imperial outpost with the criminal ambitions of high-school-teacher-turned-drug-lord Walter White of the TV series Breaking Bad. The show has since spawned a prolific, if not prosperous, tourism industry that allows fans to tour shooting locations.

But if Breaking Bad has given Albuquerque’s tourism industry an unexpected lift, visitors looking for the real thing should check out the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, when the early fall offers the best climatic combination of warm, sunny days and cool, crisp nights. Albuquerque has hosted the event for almost half a century and last year’s edition drew more than 500 hot air balloons and 108 special-shaped balloons to the Land of Enchantment. This year’s festival runs from Oct. 7 to 15.

The highlight of the festival is its Mass Ascension, when hundreds of balloons lift off from Albuquerque’s Fiesta Park around 7 a.m. Balloons launch in two waves with launch directors — known as zebras because of their black-and-white outfits — serving as traffic cops. A balloon flying the American flag to the strains of the Star Spangled Banner leads this procession, which many have called the “world’s most photographed” event. No wonder — close to a million people attend. If this sounds too bombastic, ballooning is a year-around activity in New Mexico, so visitors can pursue it on their own schedule. It certainly promises to be a soaring experiencing, as New Mexico offers some of most photogenic scenery anywhere.

Besides balloons and beautiful landscapes, Albuquerque also boasts a wide range of cultural activities and diverse examples of architecture that honour its long history and the many people who have resided along that stretch of the Rio Grande. Whatever you do, don’t break bad and don’t make a left turn at Albuquerque.

4. Skydiving, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

What Dubai lacks in size, it makes up in ambition.

The biggest city in the United Arab Emirates offers two of the world’s largest shopping malls, one with a huge aquarium, another with an indoor ski slope. It also features artificial islands in the shape of palms that can be seen from space, and Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building at 828 metres. All of these attractions, mind you, exist in the middle of desert, and show off the wealth that Dubai has generated in a relatively short time, first through its currently dwindling oil reserves, then through its strategic decision to become a global tourist destination and traffic hub. According to The New York Times, two-thirds of the world’s population lives within an eight-hour flight from Dubai, which has the busiest airport, in terms of international travel. It handled 83.6 million travellers in 2016.

The demographics of the seven emirates that make up the UAE reflect this cosmopolitanism. As of 2013, 9.4 million people from 200 different nationalities called the UAE home. So it would not be a stretch to think of Dubai as a real-life, far glitzier version of Mos Eisley, the desert spaceport in the Star Wars universe. Dubai certainly attracts unusual thrill-seekers. Would-be visitors can book a tandem sky dive over the Palm Islands, which were artificially created for tourists, or they can float above the deep red desert surrounding Dubai. Divers jump out of a plane flying at a height of almost 4,000 metres for a free-fall that lasts about a minute before the instructor pulls the parachute. A five-minute float to the ground follows.

Dubai’s accessibility, desert ambiance and architecture make it an appealing destination for adrenaline junkies such as base jumpers Fred Fugen and Vince Reffet, who jumped off Burj Khalifa dressed in bright yellow overalls with red flares attached to their ankles. Pictures of the stunt went around the world and cemented Dubai’s image as a global playground.

5. Gliding, Iceland

In Ridley Scott’s misunderstood masterpiece, Prometheus, an oval-shaped spacecraft hovers over a barren but beautiful landscape that represents Earth before the beginning of life. In the scene, pale muscular aliens wearing robes watch as one of their own dissolves himself into a cascading waterfall, seeding the planet with his DNA.

While the scene, with its pseudo-scientific premise lifted out of the Chariots of the Gods appears as pure fiction, the landscape is quite real, with Iceland playing the part of primordial Earth. The island, halfway between Europe and North America, certainly possesses an out-of-the-ordinary aura that sharpens the senses. Likely no other place on the planet offers more real-life lessons about various geological forces that have shaped our planet. Fire and ice continue to forge Iceland into an amalgam of smoldering volcanoes, swooshing geysers and shimmering glaciers, which would-be visitors can appreciate from several vantage points, including the cockpit of a glider. The glider’s appeal lies in what is absent: the potentially deafening and likely distracting roar of an engine.

Motorized forms of aviation are more predictable because they don’t rely on natural air currents to maintain lift and propulsion, but they lack the serenity of non-motorized forms such as gliding. A glider flight is also more personal since modern-day gliders can carry no more than two people, pilot included.

To be clear: Would-be visitors to Iceland who want to view it from above might brace themselves for disappointment. By virtue of Iceland’s location south of the Arctic and north of the warm Gulf Stream running through the Atlantic, its weather can be variable, if not unpredictable. Alternatively, visitors can descend into a dormant volcano. That said, soaring above the island promises a unique visual experience through space and time, no computer-generated imagery necessary.

6. Whitewater rafting, Zambezi River, Congo

The Washing Machine. Stairway to Heaven. Gnashing Jaws of Death. These are just some of the names of the 25 rapids that line the Zambezi River after it comes down the famed Victoria Falls and cuts through a narrow but long basalt canyon on its way towards the Indian Ocean. These monikers point to the intensity that awaits rafters and make Africa’s fourth-largest river, after the Nile, Congo and Niger, perhaps the top destination for whitewater sports enthusiasts.

While all whitewater sports such as rafting and kayaking feature “countless unknown, and even unknowable, hazards” as Roy Hunter writes in the Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, the “fatality risk of whitewater boating is on par with other adventure sports,” according to David Fiore, a medical doctor writing in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. That said, caution should be the guiding principle in whitewater sports, starting with the simple act of wearing a life vest. As the American Whitewater Association notes, “a third of all whitewater accidents could have been prevented if the victim was wearing a life vest; many deaths occur in very easy rapids.”

Overall, the International Scale of River Difficulty recognizes six classes of rapids, with the sixth class representing extreme and exploratory rapids that have “almost never been attempted and often exemplify the extremes of difficulty, unpredictability and danger.” In light of this description, travellers wishing to experience a level of excitement below this terrifying threshold can choose from a wide range of rivers around the world. However, rafting the Zambezi River promises to be a unique experience. Starting just below Africa’s largest waterfall, rafters experience rapids ranging from Class 3 (intermediate) to Class 5 (advanced). Rafters can launch from either Zambia or Zimbabwe and can choose among one or multiple-day trips down the Batoka Gorge. Interested parties should check with local rafting providers prior to arrival as water levels dictate the rafting season, with the river closed sometime between March and May.

7. Cliff diving, Santorini, Greece

Simple in theory, difficult in practice, cliff diving combines kinetic artistry with athleticism against a natural backdrop. However, as Nicholas DeRenzo of USA Today notes, “cliff diving is a precision sport that requires impeccable timing and an intimate knowledge of the particular cliff on which you are standing.” Within seconds, divers must calculate the distance they must propel themselves into the air to miss the rock wall, the angle and speed of the entry into the water, length of the wave swells and water depth during different tides. Cliff diving, in other words, features multiple moving parts and can quickly lead to disaster.

“It’s no cliché: mere seconds could mean the difference between life and death,” writes DeRenzo. This reality creates two choices: Watch the professionals in famed locations, such as Mexico’s Acapulco or try out some of the more amateur-friendly diving locations such as Kamari Beach on the Greek island of Santorini, the main island of an archipelago in the southeastern Aegean Sea. The island — like the archipelago itself — is all that remains after Thera — Santorini’s classical name — experienced a massive volcanic eruption halfway through the second millennium BC, an event that historians have linked to the decline of the ancient Minoan civilization. Indirect references to this late Bronze-Age catastrophe have appeared in the records of several civilizations and scholars have linked the eruption to the Jewish exodus from Egypt as well as Plato’s discussion of Atlantis.

Leaving aside these scholastic controversies, the water in Kamari Beach shimmers a bright blue and is deep enough for amateurs who want to jump off the 10-metre-high cliff overlooking the beach. The island itself attracts a mixture of tourists, some from the jetset crowd, others more rugged. All, no doubt, see the attraction of diving into a place blessed by stunning scenery and shrouded in myth — whether or not they take the literal plunge.

8. Surfing, Tahiti

The first European recording of surfing dates back to 1769, courtesy of naturalist Joseph Banks, who accompanied British explorer James Cook to the Pacific island of Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus. Referring to the “high surf” falling upon a shore, he said: “a more dreadfull one I have not often seen.” Banks also observed 10 or 12 “Indians” whose “chief amusement was carried on by the stern of an old canoe. With this before them, they swam out as far as the outermost breach, then one or two would get into it and opposing the blunt end to the breaking wave were hurried in with incredible swiftness.” Banks and his fellow Europeans admired this “wonderful scene for full half an hour, in which time no one of the actors attempted to come ashore, but all seemed most highly entertained with their strange diversion.”

Nearly 250 years later, this “strange diversion” has spread beyond the Polynesian Pacific to become one of the most popular forms of water recreation. Yet Banks’ account captures the enduring appeal of surfing as a seeming defiance of gravity. It also points to the magnitude of waves that continue to attract the world’s most daring surfers to Tahiti, specifically the village of Teahupo’o on the southwestern coast of the island. The world’s leading surfers, such as Evan Geiselman, say this location offers the best surfing. “It’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever been, with the most beautiful waves — it’s heaven, really,” he told the The New York Times in 2016. “Teahupo’o is one of the most iconic waves in the world; you can surf these heavy, big barrels.” There’s no denying that Teahupo’o, nicknamed Chopes (pronounced Cho-po), is the domain of the world’s best surfers. But Tahiti offers waves for everyone, with the prime surfing season running from March through October.

9. Great white whark diving, South Africa

Steven Spielberg’s cinematic adaption of Peter Benchley’s novel about a great white shark terrorizing a seaside town appeared in theatres 40 years ago. Yet Jaws has remained a cultural touchstone that triggers a visceral reaction, conjuring up ominous horns and hard-charging strings, clashing with each other in a sonic synthesis of fear. As Erik Vance of National Geographic writes, “there are more than 500 species of shark, but in popular imagination there’s really only one.”

It is this reality that likely explains the tourism appeal of great white shark diving off the South African coast. The concept — like its mechanics — is simple. Would-be visitors wearing wetsuits squeeze themselves into cages, which operators then lower into the water. Occupants then get a close-up look at the animals, which are baited with chum or seal decoys.

While marine biologists have used cages for some time, “cage diving” became a commercial endeavour in the early 1990s. Cage diving is especially popular in South Africa, whose waters around Dyer Island near the town of Kleinbaai are among the best spots to view one of the world’s most nomadic creatures, according to the The New York Times. The Guardian, meanwhile, reports that “shark safaris” attract an estimated 100,000 visitors annually. But for all of its popularity, various groups, including divers, surfers and fishermen consider cage-diving problematic because it teaches sharks to associate food with humans, a charge supporters deny by noting fishermen have used chumming without controversy for a long time. As Vance writes, the “great white shark is the ocean’s iconic fish, yet we know little about it, and much of what we think we know simply isn’t true.” The number of great white sharks is small — somewhere between 4,000 and 25,000 — no one really knows for sure and attacks on people are “incredibly rare.”

Surfers off the Californian coast, for example, stand a one-in-17-million chance of being attacked. For swimmers, the chance is one in 378 million. In this sense, cage diving for great white sharks may give our fears a face.

10. Zapcatting, St. Andrews, Scotland

Ever thought about skipping across the water like a flat rock at high speeds?

Zapcatting might be just the thing for you. Zapcats are small, light, inflatable catamaran hulls propelled by powerful engines. Zapcats lack seats, harnesses and steering wheels. Typical rides feature two people: a pilot who controls the Zapcat through a tiller system and a passenger who helps control the craft by shifting his or her weight.

Wearing fully enclosed helmets and life vests, both lie flat on the Zapcat as it zips across the water, reaching speeds in excess of 60 kilometres per hour. But that is not the half of it. Zapcats can perform turns of 90, even 180 degrees at these speeds, thereby exposing riders to gravitational forces of 3G — just below a Formula 1 car. The forces of physics can also conspire against riders by sending them and their craft up in the air. A search of YouTube speaks to this point. In short, Zapcatting is no activity for the faint-hearted or the unfit. But those who are willing to jump onto a thin piece of inflatable material while an engine churns behind them and propels them across the water should have a jolly old time. You can zapcat anywhere, but the sport appears to be popular in the United Kingdom, especially Scotland. And while in Scotland, it is hard to think of a more iconic place than St. Andrews. Steeped in history, it is, of course, the historic home of golf, a sport nothing like zapcatting, but variety has its virtues.

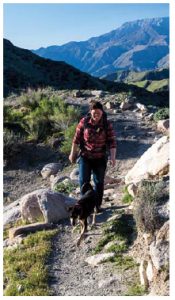

11. Pacific Crest Trail, United States

The sports on this list all share the following traits: they can induce a sudden thrill in a relatively short amount of time with relatively little preparation. Hiking the Pacific Crest Trail is the very opposite. It is a gruelling test of endurance that requires much preparation.

The Pacific Crest Trail cuts a 4,200-

kilometre swath across the length of the United States from the Mexican to the Canadian border, traversing three states — California, Oregon and Washington — and their diverse ecosystems, ranging from desert to the high alpine and the Pacific rainforest. But if these are the basic facts, they fail to capture the difficulties that confront hikers. More people have climbed Mount Everest than hiked the entire length of the Pacific Crest Trail. As Nicholas Kristof recently wrote in The New York Times, the Pacific Crest Trail is a trail of “extremes” as it “meanders through cactus and redwoods, challenging humans with rivers and snowfields, rattlesnakes and bears.” Travellers may go up to 50 kilometres without access to water. Other times, they may face the prospect of too much water as they bridge raging streams or extensive snowfields. So the trail requires a healthy amount of respect, if not awe, for the obstacles that wait ahead.

Those who do their homework, however, and those who train their body and mind, can expect an experience like no other. As Kristof and many others have said, the trail holds the promise of spiritual healing through a communion with nature that forces us to focus on the essential by eliminating the superfluous. This process of self-discovery is a prominent theme in popular literature about hiking the trail, as exemplified in Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. While Strayed’s account has led to a spike in hikers on the trail, the trip remains a formidable challenge whose thrill lies in testing the limits that we and nature impose upon ourselves.

12. Animal-watching, Chernobyl, Ukraine

What happens to nature after human hubris? That question has generated a growing interest in one of Europe’s largest genuine wild sanctuaries, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Its origin lies in the events of April 26, 1986, when Reactor No. 4 of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded. Forty-nine people died from the immediate effects of the explosion, which spread radiation across Europe. The United Nations has also linked 4,000 premature deaths to the disaster, which forced authorities to evacuate more than 130,000 individuals, many at a moment’s notice. Remnants of their former presence remain scattered across the region, in no place more so than Prypjat, a town created to house the power plant workers and their families. Forced to flee their homes, they left behind personal items of every sort, invoking feelings that alternate between the comically surreal and the melancholically touching against the backdrop of an abandoned city, its walls as shattered as the lives that once inhabited them.

The near-absence of humans in the area, however, has allowed animals such as beavers, boar, bison, foxes, lynx and wolves to flourish. A rare breed of wild horses has found a new home in the exclusion zone after authorities introduced it. This proliferation of wildlife has not just inspired biologists interested in the scientific study of this unique ecosystem, but also tourists from around the world.

An official tourist destination since 2011, Chernobyl and its surrounding countryside reportedly drew 10,000 visitors on the occasion of the disaster’s 30th anniversary. To be clear, however, travel in and out of the zone is subject to a long list of rules. Travellers cannot consume berries and apples growing in the zone, for example. While far higher than the norm, radiation levels are safe, but hot spots remain. The 5,000-plus workers who service and protect the abandoned plant follow a three-week in, three-week out schedule. Others are more permanent. Approximately 130 elderly people, known as the Samosely, live permanently in the exclusion zone. They are the living ghosts of a different era.

13. Caving, northern Spain

Caves have long fascinated humans. Our Stone Age ancestors used them as utilitarian shelters, artistic canvasses and burial grounds. Ancient myths and modern religions cast them as a stage for their larger messages. The world’s most famous allegory in philosophy by the world-famous Plato frames humans as prisoners inside a cave, where their lack of education and enlightenment condemns them to experience reality as a shadow play. Others see caves as living organisms. “They have bloodstreams and respiratory systems, infections and infestations,” wrote Burkhard Bilger in The New Yorker. “They take in organic matter and digest it, flushing it slowly through their systems.”

Bilger wrote these words in a piece about extreme caving that described, among other elements, an exploration of the Chevé system of caves in Mexico — “a kind of Everest expedition turned upside down.” The comparison is appropriate. Extreme caving expeditions can last for days and involve the same techniques, tools and hazards as mountaineering, minus the snow, but including spiders, snakes and bats, not to mention diseases caused by fungi (histoplasmosis) and parasites (leishmaniasis) that leave behind nasty lesions and even lead to death. That said, travellers looking to conquer some of the world’s most fascinating crevices do not need to spend months of preparation and huge amounts of money to get a taste of the dark deep. Northern Spain, for example, features a series of fairly accessible caves.

Consider the Arrikrutz Cave in the Basque country. For as many as three hours, groups of up to 20 people can explore the cave, itself part of a huge and complex 14-kilometre cavity of underground galleries. The cave features an underground river, enormous stalactites and includes a series of skeletons, complete with a one of a cave-dwelling lion, the only one of its kind, discovered on the Iberian Peninsula.

14. Black-Light Boulder Challenge, St. Gallen Switzerland

It comes as no surprise that Switzerland is the place for mountaineering and other climbing activities, such as bouldering and rock climbing.

As The World Factbook of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) dryly notes, its terrain comprises “mostly mountain” as the Alps cover about 65 per cent of Switzerland’s territory. Home to perhaps the most iconic mountain, the Matterhorn, Switzerland has produced a list of famous mountaineers, including Erhard Loretan (1959-2011) and Ueli Steck (1976-2017). They — and figures before them — have inspired millions around the world to climb with or without harness.

According to the 2016 Outdoor Participation Report, almost four per cent of all Americans pursued some form of climbing. One reason behind this growing interest has been the proliferation of indoor climbing gyms. Once an activity with which outdoor mountaineers kept themselves in shape during the off-season, indoor climbing has become popular on its own.

The Kletterzentrum in St. Gallen speaks to this point. Self-described as Switzerland’s “prettiest” indoor climbing gym, the Kletterzentrum’s exterior is a tribute to cubism, its interior an M.C. Escher picture come alive, as climbers crawl up and down multi-coloured walls that seem to fold upon themselves. Overall, the facility offers 2,500 square metres of climbing space to climbers of various skills. Other services complement the facility’s central purpose. They include a licensed bistro, seminar rooms and a children’s play area. But if this sounds all rather too relaxed, those looking for an extra adrenaline kick can check out the Blacklight Boulder Challenge. It is a climbing competition that sees competitors climb routes of various difficulties by following black lights. After the preliminaries, finalists then have three minutes to complete the final challenge.

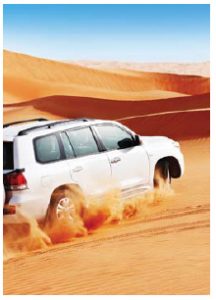

15. Sand-dune bashing, Qatar

Not surprisingly, sand-dune bashing is rather popular on the Arabian Peninsula. For young local men in the region, it is one of their major forms of recreation and the combination of youthful risk-taking amidst tricky terrain produces no small number of dangerous, even deadly, outcomes among less experienced drivers.

Dune-bashing is certainly far more sophisticated than it sounds. As Caitlin Uttley of howstuffworks.com notes, it combines “driving in mud and driving over hills.” Angles and speed are crucial to sand-dune bashing. As drivers approach any dune, they have to have sufficient momentum to carry them up. Those who start too slowly have to back down the dune or make a wide arc to drive back down At the same time, drivers heading up a dune have to choose an angle that does not see them pile-drive their bumpers into the sand. Similar calculations apply when at the top. “If you don’t know your break-over angle, you may become stuck at the top of dune,” Uttley notes, or worse. In short, dune-bashing requires considerable skill and familiarity with the terrain, which is likely why most dune-bashing operators in Qatar leave the driving to professionals. Tours generally take place in broad-tired SUVs with four-wheel drive and operators offer tours that combine the experience with other activities, including overnight camping amidst the expansive, seemingly unceasing and ever-shifting dunes.

Wolfgang Depner has taught political theory and international politics at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan campus. He now lives in Victoria.