Two hundred years after the War of 1812 began, the war, and the question of who won, remains lodged in the Canadian tendency toward cultural mythologizing. The war was fought between Great Britain and the United States and involved Upper and Lower Canada (today Ontario and the southern portion of Quebec, respectively) and many First Nations. It was a broad war, fought in the Canadas and across the present-day states of New York, Maryland, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Louisiana and Alabama as well as on the Great Lakes, the Atlantic coasts of North America and Great Britain and all the way to British Guyana. We commemorate it in Canada but in Great Britain and the United States it is largely forgotten. Many — perhaps most — Canadians think of it as a war that Canada won (burning down the American White House in the process). Canadians tend to forget that in 1812, Canada was a British colony. Fighting so far away from the Empire gave the people of the colony a sense of belonging to the colony more than to Britain, and, in some ways, a sense of nationhood grew from that.

National identity is partly built on legend, which invokes heroes, whether we raise them from the playing field or the field of battle, or mythologize them in our history books. Among the heroes of the War of 1812 are Sir Isaac Brock, the “saviour of Upper Canada”; American president James Madison; Tecumseh, chief of the Shawnee nation; and of course, Laura Secord, who warned the British of an impending American attack. The war also produced the American national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner, whose “rockets’ red glare, bombs bursting in air” refers partly to the explosions of British Congreve rockets fired at the American Fort McHenry (during the Battle of Baltimore, Maryland, September 12-15, 1814).

The conflict originated in the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), a series of wars between France and nearly everyone else in Europe, driven by Napoleon’s desire to rule all of Europe by creating puppet states. The wars caused Great Britain to adopt measures that the United States found somewhat irksome, in particular blockades that cut off the Spanish-American colonies, making the colonies dependent on British trade for European goods. Napoleon responded to the blockades by establishing the Berlin Decree on November 21, 1806, intending to cripple British trade by closing European ports, and the Continental System, which decreed the seizure of neutral and French ships that had visited a British port prior to a continental port. Great Britain countered with orders-in-council that forbade its colonies, allies or neutral powers from trading with France and imposed restrictions on neutral vessels wanting to trade at continental ports.

Tensions escalated when the British began searching American ships for contraband and for deserters from the Royal Navy. Life in the king’s navy was nasty, and many British mariners took jobs on American vessels and were granted American citizenship, which made no difference to the Empire. Besides retrieving deserters, the British began to press American-born sailors into service. The situation grew worse in 1807 with the Chesapeake Affair. British sailors from a squadron watching for French ships near Chesapeake Bay deserted to enlist in the American navy. Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys, commanding HMS Leopard, sent a boarding party to USS Chesapeake, commanded by Commodore James Barron. When Barron refused to accede to demands, the 50-gun Leopard opened fire on the 38-gun Chesapeake, killing three and injuring 18, including Barron. The British boarded and captured four sailors, three of whom were American-born, each claiming to have been pressed into British service. In 1811, the impressment issue became untenable when the HMS Guerriere impressed an American sailor from a coastal vessel.

In Washington in 1812, President James Madison was informed by Major General Henry Dearborn that Canada would be an easy conquest and that Canadians would even welcome an American invasion. At the same time, Madison was being harangued by the “war hawks,” a group of republican congressmen, puffed up by anti-British sentiment and visions of manifest destiny, who demanded war as retaliation for the blockades and for the British having encouraged the First Nations to resist American westward expansion. Some predicted an easy victory — Thomas Jefferson famously said that the conquest of Canada would be “a mere matter of marching,” and Henry Clay, governor of Kentucky, boasted that the Kentucky militia could take Canada on its own. Madison was no war monger, but he caved to the pressure and on June 1, 1812, submitted to Congress a request for a declaration of war. Congress voted in favour three days later and the Senate did likewise on June 17. On June 18, 1812, President James Madison signed a declaration of war against Great Britain.

The Americans outnumbered the British and Canadian troops. They saw their easiest target as Upper Canada, which was predominantly American and lightly defended, unlike remote Lower Canada, which was protected by Quebec’s fortress, and the Maritime provinces, which were protected by British naval power. However, the Americans were unaware of how well prepared the British were, largely thanks to Major General Sir Isaac Brock, the administrator of Upper Canada. He had established defensive measures long before war was declared, and had wisely made allies among the First Nations, including Tecumseh. With only 1,600 regulars available, Brock believed that the best defence was a strong offence that would incite the population, including the First Nations. He acted boldly, handily taking the American fort at Michilimackinac Island in Lake Huron on July 17.

In August, against the counsel of his advisers, Brock advanced on Major General William Hull’s troops at Detroit, preceded by Tecumseh and his warriors who had established themselves in the forest north of the town. Hull had no way of knowing how many warriors there were, but he feared them and thought there may be thousands. There is no real evidence to support the popular story that Tecumseh marched his men three times through a forest clearing to give the impression of a larger force. British ships shelled the fort with no real physical impact and Hull surrendered to Brock without firing a shot. It was a great victory, and one that many considered the saving of Upper Canada.

At Queenston Heights, (Niagara-on-the-Lake), although it resulted in another British victory, Brock’s audacious decision to launch a direct attack on the Americans without waiting for reinforcement proved rash. As he led his troops, he was shot in the chest and died instantly. Contrary to myth, Brock did not say “Push on brave York Volunteers.”

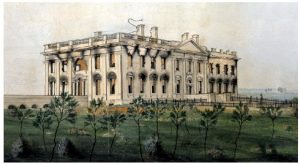

Brock’s loss was devastating, but the British did “push on” as the American campaign of 1813 focused on cutting the link between Upper and Lower Canada. Rather than taking Kingston, the logical choice, the Americans turned to York (Toronto), a lesser prize, briefly occupying it in May and burning the public buildings as they left town. Setting a place ablaze was sure to frustrate the enemy and both sides used the tactic, partly as strategy but largely as retaliation, as it turned out. The retaliatory burning culminated in British troops burning the White House in August 1814.

In May 1813, a large American army captured Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and in June the British won the Battle of Stoney Creek. Shortly afterward, the 49th Regiment, led by Lieutenant James FitzGibbon, set up camp at Thorold close to Beaver Dams, while First Nations scouts watched for American troops led by Lieutenant-Colonel Boerstler of the 14th Infantry.

In the middle of all of that was Laura Secord, wife of Sergeant James Secord, who had been wounded at Queenston Heights. While she was nursing him back to health in June 1813, with the village of Queenston occupied by Americans, they were forced to billet American officers in their home. In some way, Laura heard about the plans to attack the British at Beaver Dams and, with James unable to make the trek, she set out herself to warn FitzGibbon. Along the way she was assisted by a group of First Nations.

It was a dangerous journey, made even more dramatic in the retelling; some of the stories have her barefoot and leading a cow, which she supposedly milked in front of American sentries. Secord never revealed how she learned of the attack and it is uncertain if she reached FitzGibbon ahead of his own Aboriginal scouts. FitzGibbon did write letters of support for her later appeal for a government pension for her actions, but he provided no details concerning the timing of her warning. (Secord has been memorialized many times, most famously in chocolate. But chocolate has no connection to her or the war; company founder Frank O’Connor chose her name because she “was an icon of courage, devotion and loyalty.”)

The war reached its official end on Christmas Eve 1814 with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which determined that all conquests were to be restored and the boundary disputes deferred to joint commissions, essentially maintaining the pre-war status quo. Unfortunately, the news didn’t reach North America until February and in the meantime the Battle of New Orleans was a major American victory that assuaged American feelings over the burning of the White House. New Orleans was not the last engagement of the war, however; there were several naval skirmishes, including the absolute final battle of the war, which was fought in the Indian Ocean in June 1815 between the US sloop-of-war Peacock and the East India Company cruiser Nautilus.

The War of 1812 is neither the longest nor bloodiest war ever, but its conclusion is perhaps the most ambiguous. The situation in Europe had changed with Napoleon exiled to Elba. The peace treaty did not solve boundary disputes nor did it address impressment or maritime rights. Canada was not annexed to the United States, as the war hawks had hoped. There was no absolute victor, but it is clear that the First Nations lost. Tecumseh’s death at the Battle of the Thames broke up the confederacy that was his goal in supporting the British. The First Nations’ defeat ended their hopes of stopping American expansion into “Indian Territory.” The British abandoned their Aboriginal allies, breaking their promises as they had so often.

In Canada, the seeds of nationalism were sown by the belief — mythic or not — that “we” had won the war whose outcomes shaped our present geography. National identity has had much to do with the mythology of the war for both Canada and the United States, but more so in Canada, given our seemingly endless quest for a discernible identity. Though it’s not clear if the war was a win, loss or draw, perhaps that doesn’t matter 200 years later; we have our heroes.

Laura Neilson Bonikowsky is an Alberta writer.