In the fall of 2017, there were two events in Asia that will set regional patterns into 2018 and beyond.

First, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s secretary-general speech to the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress in October contained his declaration that he would continue to work toward the “Chinese Dream” of becoming a developed country and that China was ”ready to become a leading global power by the mid-21st Century.” He further pointed out that China will “always be assertive and strong” while safeguarding its sovereignty, territorial integrity and core interests “because there is no room for compromise.”

Second, U.S. President Donald Trump’s first trip to Asia in November was a marathon tour covering five countries, including Japan, South Korea, China, Vietnam and the Philippines. He also attended three major regional conferences. Throughout the tour, he called for his “America First” agenda to define the new geopolitical view of Asia from the Trump White House. Trump has continued to call for bilateral economic agreements from a U.S. position of strength rather than multilateral trading pacts, and for continued security alliances only with his Asia allies paying more for stationed U.S. military forces and increased purchase of U.S. armaments.

1. China: party, economy, environment

The 19th party congress added “Xi Jinping thoughts on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era” to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) constitution. As The Economist editorialized, “his ideological authority is now uncontested. That could make governing smoother, but it increases the chances of bad policymaking and complicates succession.”

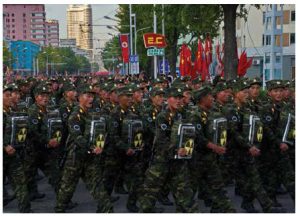

Even so, there is likely to be a continuing anti-corruption campaign to reduce ongoing state, party and military corruption as well as to purge political critics and possible future internal opposition to his strongman rule. Similarly, People’s Liberation Army (the Chinese armed forces) commanders have pledged their loyalty to and protection of Xi as the chairman of the powerful Central Military Commission. Xi has already declared that the restructuring and modernization of the army, navy, air force and the strategic rocket forces is a primary party and government objective.

Even though its economic growth has slowed compared to the previous two decades, China’s economy still needs to pursue technological input while combating its heavy pollution problems. The Chinese government’s ambitious “Made in China 2025” plan is intended to achieve global domination in cutting-edge technologies such as super-computers and artificial intelligence within a decade, but this well-funded approach to control emerging “technologies of tomorrow” has worried industrialized countries, including the United States and Japan.

At present, China is dependent on coal-fired plants for 70 per cent of its electricity generation, even as it tries to decrease dependence in an effort to curb pollution. This conflict will have major impacts on its industrial (especially iron and steel) production and manufacturing and on employment numbers as steel and coal employees are laid off thanks to an increasing shift toward renewable energy sources.

2. China and cross-strait relations

In his speech to the 19th CCP congress, Xi stated that the CCP had “the resolve, confidence and ability to defeat separatist attempts for ‘Taiwan independence’ … [CCP] will never allow anyone, any organization, or any political party, at any time or in any form, to separate any part of Chinese territory from China.” He later added that the CCP is “ready to share development opportunities on the mainland with our Taiwan compatriots.”

Then, during Trump’s visit to Beijing, Xi stated that Taiwan was the most important and sensitive issue in Sino-U.S. relations. As such, many Taiwanese observers have expressed concern that Trump may use Taiwan as a “bargaining chip” in an overarching Henry Kissinger-inspired “grand bargain” to gain Chinese support in dealing with the North Korean nuclear-missile threat. Trump is also seeking to gain Chinese agreement on concessions to commercially benefit American business in China as well as to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with China.

Direct cross-strait contact at the ministerial level has been cut since President Tsai Ing-wen’s DDP government took power in May 2016, with China constantly attempting to block Taiwan’s participation in international organizations and forums. But recently there was a report of cross-strait co-operation on detecting earthquakes for mutual benefit.

3. Trump’s Indo-Pacific strategy

Prior to Trump’s two-week tour of Asia, H.R. McMaster, his national security adviser, stated that Trump’s trip would focus on three regional goals: “First, strengthening international resolve to denuclearize North Korea; second, [promoting] a free and open Indo-Pacific region; third, [advancing] American prosperity through fair and reciprocal trade and economic practices.”

This reflected the Trump White House’s security and economic concerns in Asia. Upending former president Barack Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” policy, Trump’s “America First” agenda appears to be changing the United States’ strategy to focus on a broader Indo-Pacific view from Obama’s Asia-Pacific one. This change has meant reviving the quadrilateral security dialogue grouping of Australia, India, Japan and the United States to more closely co-ordinate their security and economic planning in the Asian region. Some observers see it as a regional financial and infrastructure counter to China’s One Belt, One Road development initiative in Asia.

4. War on the Korean Peninsula?

Trump, with his unscripted public statements and his Twitter account, and North Korean President Kim Jung-un’s public insults via the KCNA state media will continue a “war of words” into 2018. But is there a risk of war breaking out? Trump has declared that the U.S. is not at war with North Korea, despite the latter’s nuclear weapons and ballistic missile tests.

It has been suggested that there are three possible sparks for a conflict to break out between the United States and North Korea. First would be a declaration of war by North Korea and/or the launch of ballistic missiles at American territories, forces or allies, or even an artillery attack against South Korea. Second is a North Korean detonation of a nuclear device into the atmosphere or from a missile launch into the Western Pacific. But, rather than being against international laws of war, this would be against international laws on the global environment with the resultant radioactive fallout pollution. The third possibility is the shooting down of a U.S. aircraft in international airspace (beyond the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea area) as happened in 1969 when North Korea shot down an American reconnaissance aircraft. There was no American counter-strike due to concerns about Chinese and then-Soviet communist reactions.

Despite increasingly harsh political and economic sanctions, North Korea will continue to stall for time to further develop an effective long-range ballistic missile capacity and re-entry nuclear warheads — basically becoming a nuclear weapons state with a nuclear deterrent to the perceived threat from the United States. The security tensions that North Korea is creating will carry long-term consequences for the Asian region into 2018 and beyond. Its missile and nuclear weapons threat could push South Korea and Japan to seek to acquire nuclear weapons as national protection against a potential attack from the North. But South Korea’s new president, Moon Jae-in, has said his country would not seek nuclear weapons nor would it recognize North Korea as a nuclear-weapons state. In February 2018, the International Winter Olympics will be held in Pyeongchang (South Korea) just 80 kilometres south of the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. This could be an instance for another North Korean provocation.

During Trump’s November visit to South Korea, three U.S. Nimitz nuclear carrier groups worked with Japanese self-defence and South Korean naval ships in the Sea of Japan — allied preparedness exercises that Kim has called American preparations for an invasion of the North. At the same time, members of the U.S. Congress have called for hearings into Trump’s mental stability and authority to order pre-emptive military action including nuclear strikes against North Korea under the current War Powers Act.

5. South China Sea tensions

As Xi stated at the 19th party congress, China would “never allow … [others to] separate any part of Chinese territory from China.” This national policy has been applied to the islands, reefs and shoals in the South China Sea claimed by China. Since late 2013, China has pursued extensive land reclamation and military base construction on a number of these sea outcrops. While there are counter claims for many of the outcrops, China has been able to quiet many regional complaints with sizable investment deals and arms sales. In addition, ASEAN and China have announced that talks on completing a code of conduct in the South China Sea will start in 2018.

Perhaps not surprising, China has unveiled a new dredging ship with enhanced capabilities to create further new islands in the contested waters. The dredging ship has been described as a “magical island-maker,” suggesting extensive further island building in the future — something that the Trump White House has opposed verbally and with naval “freedom of navigation” sail-bys. China is also constructing a series of floating nuclear power reactors for deployment near South China Sea islets for electricity generating, desalination plants and defence facilities.

At the November ASEAN summit, Xi downplayed concerns over China’s military buildup on South China Sea outposts as well as the prospects of conflict in the contested waters. For his part, Trump offered to mediate in the South China Sea disputes — perhaps on the model of U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt’s mediation of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War, resulting in the Treaty of Portsmouth. There were no reports of regional interest in his mediation offer.

6. Japan building anti-missile defences

In his first policy speech since his landslide victory in the snap Japanese election in October, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced plans to further build up the country’s military capabilities and to amend its pacifist constitution. He said his government would “strengthen Japanese defence power, including missile defence capabilities, in order to protect the people’s lives and peace.” In his parliamentary Diet speech, Abe promised concrete action to respond to the “escalating provocations” by North Korea’s nuclear weapons testing and its ballistic missile tests in the Northeast Asian region. He pointed to North Korea’s sixth nuclear test earlier in the year as well as two ballistic missile launches that flew over Japan, which he had described as “a national crisis.”

As local tensions have increased along the western areas of Honshu and Hokkaido islands, the Japanese authorities instituted civil alarm exercises for the possibility of a missile hit. On the night of Nov. 22, reports of a “blue light in the sky” (a burning-up meteorite) yielded many local calls to an emergency security hotline.

Japan’s military spending has increased steadily since Abe took office in 2012. During his November state visit to Japan, Trump urged Abe to buy additional American weapons systems, particularly anti-ballistic missile defences, as well as to shoulder a greater portion of the costs of maintaining the U.S. military forces based in the country, as part of their defence alliance. But this has also led to speculation that Trump was pushing for foreign weapons sales to boost American manufacturing jobs and reducing the United States’ trade deficit.

Abe’s ruling coalition secured a two-thirds supermajority in both houses of parliament. This victory will make it easier for him to achieve approval for his defence build-up. He has also said he intends to push forward with changes to the post-war pacifist constitution, but to keep its Article 9 clause, which prevents Japan from waging an offensive war. At present, Japan cannot launch offensive military actions in its own defence. In addition, parliamentary moves to revise the pacifist constitution could trigger hostility from China, North Korea and South Korea given Japan’s history of military aggression during the Second World War in the Asian region.

7. South Korea: hotlines and defences

South Korean President Moon Jae-in has openly stated that he will continue to seek direct communications with North Korea — with a particular wish to reopen the North-South hotline. But he has also indicated he would not accept a United States-North Korea rapprochement if South Korea is excluded or only dictated to by Trump. He has accepted — and paid for — the deployment of U.S. THAAD anti-ballistic missile batteries in response to the continuing missile testing by the North, and will likely buy additional American weapons systems in the future. At the same time, the United States and South Korea have agreed to lift the warhead weight restrictions on South Korean missiles for defence of the South.

For his part, Trump has expressed his desire to sell more weapons systems for South Korea’s self-defence and he’s called upon South Korea to pay more for the U.S. troops stationed there. He has also pushed for a renegotiation of their bilateral free-trade agreement, which he has declared unfavourable to the U.S.

8. Regional economic integration

At the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation forum meeting in Vietnam in November, Trump argued for his “America First” policy for “mutually beneficial commerce” through bilateral trade agreements while condemning multilateral accords in favour of what he called “free and fair” trade for the U.S. At the same forum, Xi gave a contrasting speech supporting multilateralism and called globalization an “irreversible historical trend.” He went on to state that China would continue to work toward a free-trade area in the Asia-Pacific region. Since the U.S., China and Japan are the three largest economies in the world, Trump’s “America First” trade policy is likely to significantly shift the economic dynamics between the three countries. As a first step, Trump will likely push for India’s inclusion in APEC.

9. China’s regional economic plans

In January 2017, Xi told the World Economic Forum that China should “guide economic globalization.”

Despite Trump’s claims of a successful tour of Asia, many U.S. regional allies remain doubtful about the U.S.’s commitment to security and economic relations. Faced with an American retreat from multilateral economic relations, China has begun filling the void with a number of regional economic initiatives. Its One Belt, One Road Initiative is a development strategy to establish commercial connectivity and co-operation between China, Eurasia and countries along the Indian Ocean — in effect creating an enlarged “Silk Road” trading network between China and Europe. In addition, China has created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a development bank for financial lending for infrastructure projects in these regions. China is the single largest stakeholder with 26 per cent of voting rights. Canada joined the AIIB in its second call for member investors. Both of these economic initiatives will continue to advance with regional and country projects in 2018.

China is also pursuing the conclusion of a regional free-trade area in Asia that does not include the United States. It created the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to link the 10 ASEAN countries with the six countries (China, South Korea, Japan, India, Australia and New Zealand) that have FTAs with ASEAN. Although the RCEP has missed two deadlines for the completion of its negotiations, Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — to which China is not a party — has given new impetus to it being concluded in 2018. The RCEP and the TPP are not mutually exclusive, with many countries being involved in both trade deals. With the United States withdrawing from the TPP, the remaining 11 countries, led by Japan, have been negotiating the so-called TPP-11 agreement to improve market access between member countries as well as to follow agreed-to regulatory standards. On the sidelines of the ASEAN summit in Manila, an agreement was reached on the principal clauses, however several issues remain before the pact can be signed. Canada has pushed for the continuing inclusion of human, labour and intellectual property rights.

After Japan, Canada has the largest economy in the TPP-11 grouping. Notably, the Chinese government is closely watching the outcome of the TPP-11 negotiations, perhaps with a view to joining at some point. Similarly, a TPP-11 agreement is likely to provide Canada and Mexico with greater leverage with the United States in the Trump-inspired renegotiation of the trilateral North American Free Trade Agreement that will be ongoing well into mid- or late-2018.

10. Canada’s future voice in Asia

While at the ASEAN Summit in Manila, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was able to secure an invitation from host Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte to attend and address the East Asian Summit, which takes place on the sidelines of the ASEAN Summit. The East Asian Summit is a larger ASEAN grouping, focused on security concerns. It brings together national leaders from 18 countries, including the United States, China and Russia.

In his speech, Trudeau declared that “Canada is deeply committed to multilateral institutions and fora, and the East Asia Summit is an important one in an extremely compelling and growing region of the world.” Later, he said the East Asia Summit “has become the central place for discussing Pacific issues.” But it will remain to be seen if Canada will receive a future invitation to attend the 2018 summit meeting when it is hosted by Singapore — or even to become a forum member state.

In pursuit of his Asia strategy, Trudeau visited Beijing in late 2017 to discuss launching talks on a free-trade agreement between Canada and China. But, according to media reports, agreement could not be reached on the Canadian insistence for labour and and environmental safety rights to be included and no date was set for the start of talks.

The Trudeau government has been making major efforts to raise Canada’s international profile and demonstrate it can make significant contributions to help solve the complicated problems in the world today. Many observers have suggested that this is part of a wider campaign by his Liberal government within the international community to obtain one of the 10 non-permanent, two-year seats on the United Nations Security Council. Elected by UN General Assembly members, Canada last held a non-permanent Security Council seat in 2000.

In November, Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland announced that Canada and the U.S. would co-host an international conference on North Korea. Intended to find a non-military solution to the crisis on the Korean Peninsula, the meeting — to be attended by an estimated 20 nuclear powers and regional countries — is being planned for early 2018 in Canada.

Before retiring, Robert D’A. Henderson taught international relations at several universities. He currently does international assessments and international elections monitoring.