Understanding the cuisine of Hungary, a landlocked country in central Europe, requires a look back at its history. Although it’s been the territory of the Romans, Celts, Vandals, Huns and Avars at one time or another over the centuries, the first true inhabitants of present-day Hungary where the Magyars — nomads who presumably originated east of the Ural Mountains and, over four centuries — gradually moved south and west, ultimately arriving in about AD 800 in what we call Hungary today.

Food cooked in bogracs, cast-iron cauldrons hung over an open fire, was an important feature of the lifestyle of these nomads because the food could be conveniently transported in its pot and consumed over several days. Travelling with sun-dried cooked meat and a sun-dried pasta (of which today’s tarhunya is believed to be a descendant) as well as dried milk, the Magyars boiled water and added it to their dried food to make robust stews and soups similar to today’s gulyas (known in Canada as goulash.) It is widely believed that the predominance of meat and soup in Hungarian cuisine, as well as the continued popularity of bogracs as a cooking utensil, date back to Magyar traditional cooking.

At the end of the 9th Century, when the Magyars finally put down roots in the Carpathian Basin, they began raising pigs, thus adding pork to their diet. A dramatic culinary shift occurred in the 15th Century, when King Matthias, through his Neopolitan wife, Beatrice, introduced Italian cuisine, raising Hungarian cooking to a fine art. New ingredients and techniques included pasta, onions, garlic, mace, nutmeg and the use of fruits in stuffings or cooked with meat — all elements essential in present-day Hungarian recipes.

In 1526, the Turks invaded Hungary and a mere 15 years later, Hungary was divided into three parts. The Turks ruled the central area, the Hapsburgs the west and Hungarians the south. During their 150-year occupation and rule, the Turks introduced tomatoes, sour cherries, white nougat, quince sweets, Turkish delight, rice dishes such as pilafs, eggplant used in salads, asparagus, stuffed peppers and cabbage, phyllo pastry and a sort of strudel as well as langos (a type of fried bread). However, the greatest gastronomical contribution the Turks made to Hungary has to be paprika, considered Hungary’s national spice. Initially, the upper class grew the peppers for their decorative value, while peasants used them for cooking; but in time, black pepper became very costly, which persuaded many to opt for paprika, referred to as torok bors, or Turkish pepper.

Some sources believe that grinding red peppers to become what is referred to as paprika was a Hungarian invention. As well, the Turks astonishingly changed part of the local culture by acquainting Hungarians with coffee, resulting in more than 500 coffee houses in Budapest alone by the end of the 1800s. Ambassador Bálint Ódor confirms, “These proved to be important gathering venues for writers, intellectuals and the politically astute, which assisted in launching the 40-plus years of what the Hungarians refer to as their Golden Age.”

Meanwhile, Austrian and German cooking styles began to influence Hungarian cuisine when Austria’s Hapsburg monarchy secured control of Hungary from the 17th to the 20th centuries. Hungary became famous for its cakes and pastries, plus the use of red and white wine in meat and fish dishes, which added complexity and subtlety to Hungarian cooking. Middle-class Hungarians incorporated Austrian dishes such as schnitzel, sausages and vegetable stews, thickened with flour and lard (one of which is fozelek, a traditional favourite dish today), into everyday meals. Upper-class Hungarians and Austrian aristocrats embraced the French fashion of cooking, probably initiating an ongoing love of goose liver to this day.

A melting pot

All told, Hungarian cuisine may be defined as a melting pot of its past with a culinary foundation based on its own original Magyar cuisine. Hungarians remain passionate about soups, stews, meat, pastries and paprika — the quintessential spice and pepper featured conspicuously in the country’s culinary makeup.

A long-standing culinary tradition has been to mix different meats. Pork and beef and, at times, mutton are used together not only in a Hungarian mixed grill (fatanyeros) but also in gulyas, a rich spicy soup, and cabbage rolls and stuffed peppers. Hungary’s national dish, gulyas (translated as “herdsman’s meal”) is prepared with meat, paprika, onions, cubes of potato or small bits of dough (csipetke) and other vegetables and spices such as carrots, parsley root and caraway seeds. This dish, developed by local herdsmen, originated in the northern part of the Great Plain and is said to be best when prepared with Hungarian Grey cattle. It should be noted that gulyas in Hungary is entirely different from what people outside the country refer to as gulyas, although paprika stands out as a common key ingredient. Among Hungarian gulyas dishes is porkolt, which resembles more of a stew with extra onions and a thick, heavy gravy. It comes in many versions, including an elegant fish and white meat paprikash featuring sour cream; a more complex tokany with meat cut into strips, not cubes, plus additions of bacon, sausages or mushroom; and a unique szekely gulyas that combines sauerkraut, paprika and sour cream.

Paprika and traditional flavourings

Hungarian food can be spicy due to the ubiquitous use of hot paprika; however, sweet (mild) paprika is equally popular. Actually, two types of peppers are grown in Hungary: one variety (green, yellow and red in colour) is for eating raw and in salads or for use in myriad Hungarian dishes; and the other, the spicy variety, is allowed to “red-ripen” and is then dried and pulverized into paprika. The classification and quality of the paprika depends on the variety of pepper.

Many recipes also call for fresh green peppers and tomatoes. A culinary favourite, lecso, combines three of Hungary’s most-used ingredients — green peppers, tomatoes and paprika — sautéed and served as a main course or as a base for other dishes, such as meat stew. When fresh green peppers and tomatoes are not available, a preserved mixture is on hand. A second combination, that of paprika, lard and onions, has a strong presence in the nation’s cuisine. Here, lard not only enhances the fragrance of fried onions, but preserves the natural colour of the paprika. Also, goose fat, like lard, continues to be an important ingredient in achieving the extraordinary flavours of many soups and meatless dishes, among them long-simmered red cabbage and vegetable stews. Certainly, the beloved onion alone contributes a gamut of flavour options, be they raw, sweated, seared, browned or caramelized.

Hungarians use sour cream (tejfol) to lend richness to dishes such as chicken paprikash and to balance flavours, sometimes mixing it half and half with heavy cream to produce a more refined flavour while still maintaining a piquant dimension. Herbs and spices such as dill, horseradish, bay leaf, marjoram, caraway and pepper seeds, in addition to vinegar and vanilla, appear repeatedly in Hungarian dishes.

The Hungarian pantry

Besides paprika, peppers, tomatoes, onions, sour and heavy cream, other primary staples include meat, soups, seasonal vegetables and fruits, sausages and cheese.

Hungarians eat a lot of beef, chicken and duck. Ambassador Ódor points out that “the best pork comes from the prized Hungarian breed of domestic pig called mangalica, which has a thick woolly coat like a sheep.”

Lamb, mutton, goose and game bring appealing variety to Hungary’s culinary landscape. In old-style recipes, such as the pulkamell, which uses turkey breast, fruit such as plums and apricots are cooked with meat in spicy sauces or in fillings for game, roasts and other cuts.

Hungarians have a long tradition of stuffing cabbage and peppers with ground meat, rice and spices (including toltott paprika), burying hard-cooked eggs down the middle of meatloaf (stefania szelet) to give a decorative effect of white and yellow circles once cut and of filling savoury crepes with veal stew and veal paprikash. Many meat and chicken recipes call for dipping in breadcrumbs and then baking or frying. Hungarians very often eat pork that way (Becsi szelet) or they eat it cooked with peppers, or as thin pork steaks served either with cabbage or on a platter of Hungarian mixed grill. Cured pork and bacon maintain their omnipresent popularity. As for fish, the Danube and Tisza rivers and the largest lake, Balaton, provide an abundant supply. With serious regional rivalry — “particularly between the cities of Baja and Szeged,” the ambassador says — the Hungarian hot fish soup known as halaszle, is prepared differently on the banks of those two rivers. The Lake Balaton area can lay claim to two well-loved specialties — catfish with a type of noodle/dumpling referred to as galuska and bream (varieties of freshwater fish) in cream — while the region around Lake Tisza remains particularly renowned for its not-for-the-faint-of-heart lamb stew from Karcag, where virtually every part of the animal, from head to foot, is cooked over a large open fire.

Hungarian cuisine makes use of a wide range of cheeses, but most predominately turo (a type of quark), cream, sheep and several Hungarian cheeses, plus Edam and Emmental. As an integral part of their cuisine, Hungarians can boast of the many different kinds of fabulous sausages — from spicy and/or smoked kolbosz to their world-famous Hungarian salamis. For side dishes, various types of dumplings with different fillings, noodles, potatoes and rice have always been the most common. Vegetables primarily consist of root varieties, which can be stored through the winter.

As a nation intensely devoted to soups, any proper Sunday meal must include a fine chicken soup. But the types of soups extend far beyond chicken. There’s also the renowned halaszle fish soup — another national dish in which the addition of paprika drives quite a punch — and Hungary’s famous sour-cherry, apricot and peach chilled soups. And don’t forget the soups whose main ingredients include either beans, lentils, vegetables with pinched dumplings, liver meatballs, potatoes, or even wine and caraway.

Throughout the world, Hungary has become well known, not only for its gulyas, but also its elegant cakes and pastries such as the dobos sponge cake, layered with a chocolate buttercream filling and crowned with a crust or thin slices of shiny hard caramel, and kurtos kalacs, a hollow tubular honey cake commonly referred to as chimney cake. Phyllo, the flaky pastry dough introduced by the Turks in the 17th Century, is used to make strudel, the best-known Hungarian dessert, with apple, cherry or poppyseed fillings. Palacsinta, pancakes or crêpes filled with ground walnuts and flambéed in dark chocolate sauce, rank as another outstanding dessert. As a summer treat, Hungarians love ice cream, which is known as fagylat. In addition to the regular flavours of cinnamon, poppyseed and rice, fruit flavours of ice cream coincide with the fruits of the season, starting with strawberry and cherry in the summer and pear and plum as fall approaches.

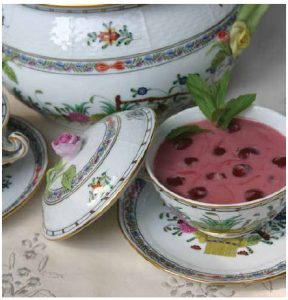

Please enjoy a little taste of Hungary with my tamed-down version of the country’s famous, and tart, sour-cherry chilled soup. Having originated in Hungary, it has become a summer delicacy in several European cuisines. Traditionally, one serves it at dinner as an appetizer, often with dollops of sour cream, or as a dessert with vanilla ice cream. Bon Appétit! Jo Etvagyat!

Sour Cherry Chilled Soup (Meggyleves)

Sour Cherry Chilled Soup (Meggyleves)

Makes about 10-12 small servings

1 jar (28 fl oz or 796 mL) sour cherries,

pitted, in light syrup

2 small cinnamon sticks

1 slice fresh orange (thickness: 1/3 inch or 0.8 cm)

5 cloves

1/4 tsp (1 mL) salt

½ cup (125 mL) sour cream (14 per cent fat)

3 tbsp (45 mL) heavy cream (35 per cent fat)

1/4 cup (60 mL) maple syrup

½ cup (125 mL) vanilla yogurt (2.9 per cent fat)

1. Place cherries with their juice in a medium-sized saucepan over medium-low heat. Add cinnamon sticks, cloves and salt; bring to a boil. Immediately reduce heat and gently simmer for 5 minutes.

2. Place a large sieve over a medium-sized bowl and drain cherries, reserving the liquid. Transfer cherries to a dinner plate; remove cinnamon sticks, orange slice and cloves and discard. Allow to cool.

3. In a medium-sized bowl, whisk together sour cream and 1/4 cup (60 mL) of cherry liquid. Continue to gradually add the remaining cherry liquid, whisking well between additions.

4. Whisk in heavy cream, then maple syrup and finally yogurt. Add cherries and refrigerate the soup at least overnight or for 24 hours to allow flavours to develop and blend. Serve chilled in 1/3 cup (80 mL) portions. (Note: this soup freezes well.)

Margaret Dickenson is a cookbook author, TV host, menu/recipe developer, protocol, business and etiquette instructor. (www.margaretstable.ca)