For many in the Western world, Madagascar will conjure up images of exotic species such as the native lemur, found nowhere else in the world, or the distinctive baobab tree, with its swollen trunk and short, outstretched branches. They think of it as resource-rich nation boasting exotic spices such as vanilla and the much-desired commodity, rosewood, or as a far-flung holiday destination for those with a love of the great outdoors and an adventurous spirit.

Yet for too many living in this remote island nation, the most precious resource of all — clean water — is still out of reach.

More than three quarters of the population here lives below the poverty line. According to data from the WHO and UNICEF’s Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply (JMP), nearly half of all Madagascans — 12 million people — live without access to basic levels of clean water, while a staggering nine in 10 people do not have access to a decent toilet. Meanwhile, data collected from the Ministry of Water, Energy and Hydrocarbons here — and supported by WaterAid Madagascar — show the reality seems to be far worse, with an estimated three quarters of the population living without access to clean drinking water, putting the country well below the average for sub-Saharan Africa.

What’s more, those figures hide huge disparities between families living in rural and urban areas. Slightly more than a third of those living in rural communities have access to clean water, while most of those living in towns and cities — 80 per cent — enjoy this life-saving resource.

This means that every day, Madagascar’s poorest and most vulnerable are forced to collect water from dirty ponds or riverbeds. Those water sources are particularly dangerous, as going to the toilet in the open is rife. The consequences are disastrous; impacting people’s health, education and livelihoods. It is costing lives. Diarrhea caused by drinking dirty water is one of the leading causes of deaths in children under five in Madagascar, second only to pneumonia.

Many readers will have suffered bouts of diarrhea that pass within a couple of days, but for children living without clean water to drink, lack of toilets and poor hygiene practices, diarrhea can quickly kill through dehydration and fluid loss. If the child has only dirty water to drink, every sip is likely to contain the bacteria that caused the diarrhea to begin with, exacerbating the problem and leading to a rapid decline. If they are already malnourished, their bodies cannot fight the infection as effectively. Diarrhea also makes it more difficult for the body to absorb nutrients, so even those who survive repeated bouts are at higher risk of malnutrition though they may have plenty of food to eat. This can lead to lifelong stunting of their growth — physically and cognitively.

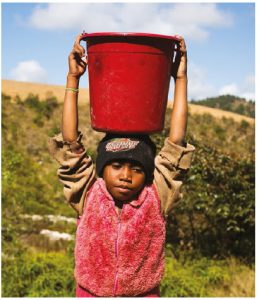

Everyone living without these basic human rights is affected, but there can be no doubt that women and girls often bear the greater burden a lack of clean water, decent sanitation and good hygiene brings. Too often, it is women and girls who are responsible for collecting water needed for drinking, cooking and cleaning and they must walk miles to do so. Too often, girls are forced to drop out of school because they lack the toilets needed to manage their periods privately. Too often, women are giving birth in ill-equipped health facilities without clean water, which means they’re denied the clean, hygienic environment needed to deliver their babies safely.

At WaterAid Madagascar, we see these realities every day. Until recently, the Belavabary commune — just a three-hour drive from the capital city Antananarivo — had no access to clean water. Initial water analysis, conducted by WaterAid Madagascar, showed water from the ponds and streams there was too dangerous to drink and yet men, women and children had no choice but to drink it every single day. In the village of Tsarafangitra, the nearest place to find water was more than 1.5 kilometres away. Young children and their mothers had to tackle a steep slope — virtually impassable in the rainy season — to reach it.

However, thanks to money donated by Aveda Canada, WaterAid Madagascar has been working to provide universal access to clean water. To date, 12 water points have been installed, serving eight communities, six schools, two health centres and more than 7,000 people.

Last year, when WaterAid met Raoly, a 29-year-old mother of three, she described a back-breaking journey up and down steep hills to collect water with her children strapped to her back. Worse, the water she and her friends spent hours each day collecting was so dirty their children would often fall sick. She even collected water from a nearby rice field while in labour for her first two children.

With WaterAid’s help, Raoly and other families in the village now have clean water close to their homes, along with the gift of time, meaning that precious hours previously spent collecting water can now be spent looking after their families, tending to livestock and farming. Women no longer have to give birth in health care facilities with dirty water from a nearby field that they themselves collected. Just last year, Raoly gave birth to her third child in a maternity ward furnished with decent toilets and clean water. And parents no longer have to fear that the water they give their children could kill them.

In the nearby village of Mahavoky, dirty water and poor sanitation meant teachers and pupils suffered as they used to go to school with no clean water to drink, no decent toilet and no way of cleaning their hands.

Six-year-old Cynthia explained to WaterAid that before water arrived in her village, she would start her day by collecting water with her mother and her siblings from a nearby rice field, leaving her tired and exhausted. She and her friends didn’t even have water to drink at school, leaving them thirsty and lethargic.

Now water points have been installed throughout the community, providing Cynthia, her family and friends with clean, running water. It has transformed her life, allowing her to enjoy the simple pleasures every child should enjoy — such as playing with her friends, taking time for her studies as well as helping her mother around their home.

There can be no doubt that clean water, decent sanitation and good hygiene have the power to transform lives. As Raoly and Cynthia’s stories demonstrate, when one community is given access to these fundamental human rights, it creates a powerful ripple effect; improving people’s health, education, livelihoods and prospects. Yet, unfortunately, Raoly and Cynthia are the lucky ones. At current rates of progress, Madagascar will not achieve universal access to water until 2069 and for sanitation, we are likely to be waiting until 2281. If we are to improve the lives of Madagascans across the country, change needs to happen now.

Lovy Rasolofomanana is the country director for WaterAid Madagascar.