When China released its Arctic policy this past January, a flurry of news articles emerged. Most attention was paid to China’s growing ties to Russia, and its significant investment in the Northern Sea Route — the seaway that is opening up as the ice melts along Russia’s northern coast. China has not constrained its interest to the Eastern Hemisphere, however. There are no caveats in China’s Arctic Policy that limit its application — the growing economic giant’s ambitions reach right across to North America as well.

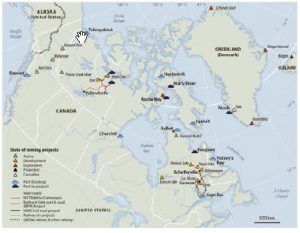

Chinese investment in the Arctic, including in North America, is growing significantly. According to the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) in the United States, from 2012-2017, China invested $47.3 billion US in Canada, which amounted to 2.4 per cent of Canada’s entire GDP during that timeframe. Due to incredible work from Université Laval and Pierre-Louis Têtu at the University of Ottawa, one can see the extent of China’s pan-North American-Arctic interest, specifically in the mining sector, in the form of direct investment.

Canada is now in the throes of developing its own new Arctic policy framework, which will produce a new domestic and international strategy. The government is tackling existential questions with Canadian Northerners, including how to address food insecurity, lack of infrastructure and the problematic history of colonialism. While the government will do its best to address these important domestic matters, the new policy must also wrestle with international dilemmas, such as what to do about China’s ambitions for the North American Arctic.

China currently appears to be an “easy fix” for the North — a source of much-needed cash investment in resource- and infrastructure-poor areas. However, there are significant security concerns associated with China’s interest in North America that must be carefully considered and balanced against the potential boon from Chinese investment. Canadians may disagree about the wisdom of accepting extensive Chinese investment and involvement in the Arctic, but their debates should be fully informed and take into account Chinese ambitions for the region.

China’s Arctic policy

China’s Arctic policy has been characterized by two major things: First, the outright statement that China has no claim to territory in the Arctic and second, its “respect” for international law. Many onlookers have given China immense credit for both statements. Although China is to be commended on its well-reasoned and sober policy, a closer reading of the document yields some reasons for North Americans to remain wary of Chinese ambition. Specifically, the policy states: “States from outside the Arctic region do not have territorial sovereignty in the Arctic, but they do have rights…”

To the first point on sovereign territory on the Arctic: What’s the alternative? Either China could have made claims to territory in the Arctic (an insane and manifestly untenable position) or China could have remained silent on the matter, possibly provoking some insecurity among Arctic nations. China’s statement on sovereign territory was politically astute, and also clever. It bought international goodwill by stating the obvious and diverted attention from its other claims, for example, to its rights in Svaalbard (a Norwegian archipelago governed by the Spitsbergen Treaty) and other notions of “global commons.”

China’s “respect for international law” has also been lauded, but this statement is something of a Rorschach test: what people see in it divulges more about them, and perhaps what they want to see, than it does about China. International law in the Arctic is primarily comprised of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). UNCLOS establishes the degree to which coastal countries retain sovereign rights over the sea. At 12 nautical miles, countries have near-total sovereignty; at 200, they retain an “Exclusive Economic Zone” and beyond 200, what remains is the “high seas,” which China claims are “open to all states.” China’s claim in the Arctic about international law is not about bolstering other countries’ rights to keep China out. Instead, China is subtly asserting its right as an international leader to access the Arctic, despite not holding sovereign territory.

UNCLOS also provides rights of passage through other countries’ territorial seas. Debates about the extent of these rights have not been resolved in the Arctic, with Canada and Russia on one side of the debate (requiring the coastal state’s consent) and the United States and the European Union on the other side (insisting on freedom of navigation, meaning that all countries should be able to use those waters as a transitway, even without coastal state consent). China has not taken a position. Siding with the United States might jeopardize its claims in the South China Sea, but siding with Canada would mean limiting Chinese access to the North American Arctic, and possibly Russia’s Northern Sea Route. China’s blanket statement about “respect for international law,” without defining what it means, enables it to seem like it is upholding the international order without saying much of substance.

China’s vision for North America’s Arctic

Last summer, China’s icebreaker, the Xue Long or Snow Dragon, transited the Northwest Passage. To avoid involving themselves in longstanding international disputes under UNCLOS, they labelled the mission “Marine Scientific Research” (MSR). Under UNCLOS, MSR requests require host-nation consent, whereas the need for host nation consent is otherwise a point of debate under UNCLOS, as discussed above. Dubbing their transit a science expedition allowed China to keep everyone happy without giving away its own position on whether it should be allowed to transit without Canada’s consent for commercial or other purposes.

Once the Xue Long returned home, the expedition was pronounced a successful test of the Northwest Passage as a commercial shipping route, much to the dismay of Canada. Although the Canadian government was likely aware that China’s interest was not purely scientific, it was internationally embarrassing that China was not willing to at least keep up appearances. China has not been shy about articulating its interest in the Arctic as being primarily economic.

China’s One-Belt-One-Road initiative began in 2010. Initially, it was announced as an investment initiative to re-establish the Silk Road. China began redeveloping trade routes across Eurasia, establishing mechanisms to connect East with West. In China’s Arctic policy, the Arctic is dubbed the “Polar Silk Road.” Although some commentators have assumed that the term “Polar Silk Road” only relates to the Northern Sea Route (the waters directly north of Russia) nothing in the Arctic policy limits China’s ambitions to those waters. The Northwest Passage and the “trans-Arctic route,” which would go straight across the North Pole once the ice melts sufficiently, are also implicitly fair game as a part of this broader Chinese initiative.

China has additional strategic reasons for pursuing an Arctic presence. For example, a series of satellite ground stations in the Antarctic have proven helpful to the Chinese space program, and they are looking to establish a similar presence in the Arctic. As China’s economic expansion reaches around the globe, it will seek strategic footholds to help it navigate and protect its interests.

China is a sophisticated rising power seeking to maintain its way of life (and its current government), expand its economy and care for its people. China has a notable and enviable ability to think in the long term, and therefore to plan and invest for the long term. The writing is on the wall with respect to the Arctic: The ice is melting and sea routes are opening up. Commerce will follow and China is positioning itself to be the world leader in the entire circumpolar region, to include all of North America: Canada, Greenland and the United States.

Chinese offers to NWT and Nunavut

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau travelled to China in December. That much-anticipated trip was expected by some to result in the promise to start negotiating a free-trade deal and the potential for multi-billion-dollar investments from China. Instead, when the prime minister took strong traditional Canadian stances on matters such as human rights and rule of law, potential trade talks were off the table. While relations between the two countries will require some work before trade talks resume (if they ever do), China has continued to develop opportunities to invest at the sub-national level across Canada, and especially in the Canadian North, as they have in Alaska and Greenland.

Canada’s north is infrastructure poor and deeply in need of investment. Canada’s new Arctic policy framework, which the government is diligently working to produce this year, will come with significant new investment for the people of the North. However, the need is great and the government has already signalled that it will not be able to transform the north overnight as its resources are limited.

China has been developing its own relationships with Indigenous groups and territorial governments. Chinese representatives have met with Inuit groups and development corporations in Nunavut, and the Northwest Territories has its own strategy to help incorporate Chinese investment. It is welcoming Chinese immigration and establishing tourism agreements, in addition to traditional foreign direct investment.

The Northwest Territories’ approach is prescient and necessary: As the Snap Lake diamond mine closes, it will need to diversify its economy. Chinese money is a promising new resource, and the Territories would need a very good reason not to take it. In Nunavut, the need for infrastructure investment has focused recently on ports and roads. The Canadian government recently agreed to help fund a port in Iqaluit, but there is also need for additional ports, including a possible deepwater port in Qikiqtarjuaq. Local leaders in Qikiqtarjuaq are “welcoming” Chinese investment for their proposed port project, especially if funding cannot be secured through Canadian government sources.

Another example is the Roche Bay iron mine, where Chinese investors hold a majority of potential equity stakes. The ultimate goal of the project, which is now in the advanced discovery phase, is to ship ore directly from Roche Bay to China, implying Chinese investment in port facilities. Chinese investors are also funding Sabina Gold and Silver Corporation mines in Western Nunavut, with the goal of shipping from Bathurst Inlet. Each of these initiatives represents an important opportunity for northern economies, which are currently suffering.

The Chinese often frame their investments as “win-win” — good for China and the receiving country. In many cases, that may be true. However, Canadians who accept Chinese investment should go into these transactions with eyes wide open. Indigenous leadership and territorial governments have expressed some ambivalence about relying on foreign investment, and especially on the extractive industries, for economic growth. There are no easy answers to addressing the needs of the Canadian north. Nevertheless, knowing the full range of possibilities, including Chinese longer-term ambitions for the Arctic and for North America, will help territorial governments navigate these difficult choices.

China’s proactive investment strategy in Greenland

While Greenland, an autonomous nation within the Kingdom of Denmark, now politically resides in Europe, geographically it belongs to North America. Greenland has been working toward achieving its independence from Denmark, and it is looking to forge its own relationships and partnerships. China has signalled its willingness to help.

According to CNA, Chinese investment currently comprises 12 per cent of Greenlandic GDP. Greenlanders have made their interests clear: They need economic independence, achieved through developing tourism and the extractive industries. As the ice melts, Greenland’s mineral resources are being uncovered, leading to immense opportunity. However, the cost of operating in that environment, which is very similar to Northern Canada, is still high; it requires significant investment and a long view. Both tourism and the extractive industries will require improved transportation infrastructure, including additional airports. After efforts from Greenland to solicit investment broadly, only China is currently underwriting three new airports.

Greenland has expressed interest in other investors, especially from North America. The current prime minister has even gone as far as seeking to adopt English as an official second language (after Greenlandic, which is closely related to Inuktitut) to replace Danish. Nevertheless, Canadian and American investment has not been as forthcoming as that from China.

Chinese interests are not purely magnanimous, nor would one expect them to be. But, China’s interests reach farther than simple return on investment. As reported by writer Jichang Lulu, China now has a satellite ground station in Greenland, opened to much fanfare in an official Greenlandic ceremony in December 2017. Chinese mining company General Nice Group also tried to purchase an old naval base in Greenland in 2016, which was blocked by Denmark due to fears that the United States would balk at having a Chinese presence in North America, and close to Thule Air Base, a small facility and vestige of the Second World War currently run jointly by Americans, Canadians, Danes and Greenlanders.

The United States and Canada have significant historical ties to Greenland from the war. When Denmark fell to Nazi Germany, the United States oversaw Greenland and established bases there. They served as important beacons, refuelling stations, weather stations, radio stations and sources of intelligence. Thule remained active during the Cold War until today, as it is strategically located at the midpoint between New York City and Moscow.

Canada has its own significant history of co-operation with Greenland. Greenland’s 90 per cent Inuit population shares close ties (including family links) with Inuit in Canada. Canada is one of the few countries with a consulate in Greenland, and relations have been consistently co-operative.

As Greenland strives for independence, it may be looking to guarantors other than Denmark for its security and defence. Given the United States’ and Canada’s historic ties to Greenland, investment from its North American neighbours would very likely be Greenland’s first choice. However, China is becoming a reliable partner for Greenland as it seeks to establish its own defence and security capabilities. If invited, it is foreseeable that China could develop the relationship further.

China developing ties to Alaska

When Xi Jinping visited U.S. President Donald Trump in 2017, he made one stop on the way home — Alaska. To onlookers who were not clued in to China’s Arctic ambitions, that trip seemed like a random stopover for some touring with Alaskan Gov. Bill Walker. To Alaskans, however, China’s interest in their economy is well-established — China is Alaska’s largest trading partner. Xi is fostering this relationship with Walker, and welcomed a delegation from Alaska, including the governor and the heads of 26 Alaskan businesses, to China in May 2018 to continue talks that began last year.

Alaskans are all too aware that they own Arctic policy for the United States. Although the United States is one of only eight Arctic nations, and one of only five nations that border the Arctic Ocean, the government in Washington has not made the Arctic a priority. On many issues, including foreign direct investment, Washington has a hands-off approach. Alaska is therefore not only the United States’ front line when it comes to Arctic policy, but on many issues, Alaska is determining the U.S. Arctic position.

As relations between Washington and Xi have become more volatile since Trump’s election, China appears to be taking a pragmatic approach, continuing to foster relationships at the sub-national level. These advanced trade and investment talks between China and Alaska are just another example of China’s commitment to the Arctic region.

Why be wary of Chinese investment

Many good things can come from Chinese investment — in certain circumstances it can truly be a win-win. However, China has shown in other analogous circumstances that it is not always forthright, and that there are some strings attached to its investments. Though some investment comes from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and some from “private” enterprises, those distinctions do not mean the same thing within the Chinese communist context as they would in the capitalist economies of North America. All investment from China has the potential for Chinese government involvement.

Australia and New Zealand can offer some insight to like-minded Canada. Although Vancouver is closer to Beijing than Sydney, Australia and China are perceived to be more closely situated. While investment from China has had a positive impact on the economy, there have been political ramifications in Australia. According to investigations by the media and the Australian government, Chinese attempts at political interference were on a scale larger than that of any other nation and China is actively attempting to infiltrate Australian political and foreign affairs circles.

Similar political problems have arisen in New Zealand, according to professor Anne-Marie Brady, a specialist in Chinese and polar politics based at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. Due to her extensive and commendable work on Chinese global ambition, she has had her office ransacked by Chinese intelligence. Even more recently, a New Zealand member of parliament was shown to be compromised by Chinese intelligence, but won re-election anyway. A recent Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) report highlights these problems in New Zealand, stating that “the impact of China’s political influence activities on New Zealand democracy has been profound.”

In South Asia and Africa, Chinese investment has grown so significant that China has established military bases to protect its interests. China’s footprint in Africa is large: Chinese nationals go to Africa to develop and build infrastructure, at the invitation of African governments. In addition, China has become an important troop-contributing nation for peacekeeping forces across the continent. In order to protect these interests, China established a military base in Djibouti, which opened in late 2017. There are recent reports of Chinese lasers from this base harassing pilots working at the nearby American base, Camp Lemonnier.

China announced in January that it would be opening another base in Pakistan. Chinese military vessels now patrol the Indian Ocean, seeking to protect Chinese interests, including their significant investment in Pakistan. Now Chinese commentators are highlighting the need for a place for those vessels to dock, resupply and refuel. Sri Lanka’s inability to pay off Chinese debt resulted in the country handing over a strategic port to China for the next 99 years.

The consequences of indebtedness to Chinese interests could manifest in North America as well. Since solicitations for Chinese investment tend to focus on infrastructure projects, there is a risk not only of a Chinese foothold, but potentially outright Chinese ownership in major critical projects. Canadians in Churchill, Man., have been struggling without resupply for more than a year, after the American corporation that owns the railway refused to repair the tracks after they were flooded. On May 23, the federal government blocked the sale of Canadian construction company Aecon to China, presumably to avoid similar potential problems in the future. It remains to be seen how the Canadian government will react to increased Chinese investment in the north, especially for projects it is not willing to fund itself.

China is behaving rationally across the world to protect its interests and project its influence. These are the predictable goals of a rising power, and ones that should not surprise North Americans, nor are they necessarily goals that should be condemned. Rather, the important thing is to be aware that China’s apparent benevolence comes from a self-interested party. As Chinese expansionism takes hold, its security and defence interests will necessarily follow.

China has also indicated its willingness to be misleading, and even lie about its intentions. That should provoke some second thought among nations looking to deal with China. In the South China Sea, China has been developing military bases on outcroppings to which they hold no sovereign territorial right, according to a Hague tribunal. Despite reassurances that these developments were for peaceful purposes, China was reported to be housing missiles on those bases as recently as May. The United States, the Philippines and Vietnam have been clamouring for international attention to China’s blatant disregard for international law and the explicit dictates of an international tribunal to which they are a signatory, as well as China’s willingness to lie about what they are up to, despite clear evidence to the contrary. Nevertheless, China’s expansion in the region has gone relatively unchallenged.

There are ways to distinguish the South China Sea from the Arctic. For the most part, China has shown itself to be a country worth dealing with, but the most prudent way forward is to deal with China with both eyes open. Chinese investment is part of a long-term plan to dominate the commercial potential of the circumpolar Arctic. Receipt of Chinese investment should therefore be thoroughly thought through, as part of a long-term plan to develop the Arctic responsibly and without interference in democracy or introduction of a military presence that can come with Chinese investment.

Lindsay L. Rodman is the International Affairs Fellow (Canada) at the Council on Foreign Relations and a visiting scholar at the Centre for International Policy Studies at the University of Ottawa.