This often-ignored region of the world has a lot to offer and a lot at stake. In this 10-part list, Wolfgang Depner looks at the good and the bad — and why the world should pay more

attention to the region.

These are, to say the least, interesting times for the Caribbean. The recent discovery of oil off Guyana has revived dreams of regional prosperity, as the region continues to recover from the devastating hurricanes that ravaged parts of it in 2017. Haiti remains a source of political instability and migratory streams, while Cuba finds itself in the middle of a domestic transition that includes a tentative, tenuous rapprochement with the United States, at the very moment that China continues to strengthen its influence in the region by inviting Caribbean nations to participate in its ambitious, globe-spanning One Belt, One Road project of trading routes and networks.

Notably, China’s interest in the region has intensified as the United States has pivoted towards the South China Sea — known as the “Caribbean” of China — bearing out the trope that if you want to play in my backyard, I can play in yours, too.

This emerging dynamic of a global Sino-American rivalry has provided Canada with a distinct local edge, given its relative proximity and its deepening ties to the Caribbean.

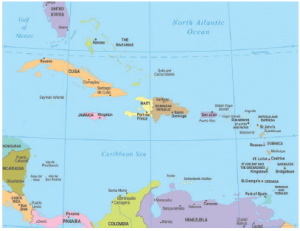

It is against this background that we have chosen to take a look at the region and its issues. Yet this choice confronted us with an immediate conundrum: What exactly counts as the Caribbean? All countries with a Caribbean shoreline? All island nations in the Caribbean? Or is it a socio-cultural space, with a unique history of European colonization and distinct economic conditions?

One obvious starting point is the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), with 15 full members (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago) and five associate members (Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and Turks and Caicos). But this list is incomplete insofar as it neither includes Cuba nor the unincorporated American territories of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, clearly part of the Caribbean by geography and history. It is also important to note that the Dominican Republic, Haiti’s neighbour on the island of Hispaniola, only holds observer status in CARICOM. In short, the Caribbean starts, but does not end, with the CARICOM countries.

Indeed, it is difficult to disentangle the Caribbean from the North, Central and South American mainland that rims it. The region hardly appears insular, for it is a major hub in every imaginable way. It’s a place that draws people from afar in the form of tourists, and generates diasporas around the world, including Canada.

Illegal migrants, drugs and funds continuously pass through it, yet it is also an attractive destination for legitimate economic investments and well-heeled immigrants from Europe and North America who are looking for a different lifestyle. It is a place where relatively well-functioning British parliamentary-style governments co-exist with authoritarian presidential systems that govern only for themselves. It is a place where human violence co-exists with natural beauty.

Without being too profane, it is where the best and worst of all worlds collide, and it deserves more of our attention.

What follows is our set of the Caribbean’s top 10 drivers and deficits.

1. Share of global economy

It does not take much effort to see the economic potential of the Caribbean.

The region has a young, multilingual population and it lies to the south of a major developed market (the United States) and to the north of several emerging markets of South America (including BRIC member Brazil). Geography has also blessed the Caribbean nations with some of the most popular and iconic tourism destinations.

While the region is home to one of the poorest countries in the world (Haiti), most Caribbean nations have fared relatively well since the 1960s and 1970s, when the region largely decolonized.

Measured against emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), most Caribbean countries now rank among the top 25 per cent globally.

Yet these findings — which appear in an IMF report titled Unleashing Growth and Strengthening Resilience in the Caribbean and published in 2017 — need to be held against the larger point that the region is still trying to fulfil its potential.

As the report notes, the region has not reached the living standards of advanced economies. “No single reason can explain the Caribbean growth slowdown,” it states. “Drivers include both large adverse external developments and, more important, persistent domestic macroeconomic imbalances and structural impediments.”

External events include, among others, the region’s susceptibility to natural disasters. Persistent macroeconomic imbalances include what the report calls a vicious cycle of high government debt levels and low growth hampered by several structural deficits.

Three stand out. First, the high cost of energy undermines regional competitiveness by raising the cost of doing business, especially in the important, but energy-intensive, tourism sector. (When measured on a per capita basis, according to the report, Caribbean economies that depend on tourism appear to be more energy intensive than Caribbean economies that export commodities such as Belize, Guyana and Suriname.)

While electrification rates in the Caribbean hover around 90 per cent, according to the World Bank, electricity costs have increased by almost 80 per cent between 2002 and 2012.

The region’s reliance on expensive imported oil primarily accounts for this price problem. Except for Trinidad and Tobago — the only net exporter of oil and natural gas — all Caribbean countries are net oil importers. This reliance accordingly exposes the region to unexpected price shocks that compound existing fiscal and trade imbalances. Worse, local energy systems often struggle to deliver this expensive energy to their consumers on a reliable basis because they are outdated and have capacity problems compounded by a lack of technical expertise.

Second, the Caribbean continues to lose some of its best. If Caribbean emigrants still lived in the region, they would account for about 22 per cent of the population, and many of them are among the best educated.

Nearly half of Caribbean emigrants to the United States have at least a college education and generally tend to be employed in the health-care sector and various white-collar occupations, where their hourly wages average about 60 per cent more than those of immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

While their remittances are important, they do not outweigh the harmful effects of this Caribbean brain drain, such as lost productivity and innovation. It is doubly worse when we consider that the face of Caribbean emigration is female. Among Jamaican-born women living in the United States (who emigrated after age 22), 50 per cent have at least a college education — double the attainment rate in the home country, where one-quarter of women have a college education, according to the report.

Third, the region has a violent crime problem (see more under governance) because of its status as a transit zone for illegal drugs flowing from Central and South America into the United States, illegal human trafficking and general corruption.

Globally, the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region has the highest homicide rate, according to the IMF, with Caribbean homicide rates below those in Central America, but above those in the southern cone of Latin America.

“More worryingly, the IMF report notes, the victims of violent crime are predominantly young, which can have a significant bearing on economic and social outcomes both in the near term and in the long term.”

The high violent crime rate in the Caribbean has not only a human cost. It also requires an expensive response.

The IMF: “Because the public and private sectors often have to spend large amounts of resources, both to prevent crime and deal with its negative consequences, it can have a significant impact on economic prospects, particularly in the Caribbean, where many economies are stuck in a low growth-high debt trap.”

2. Carving up the Caribbean

As the 19th Century turned into the 20th, it had become clear that the United States was emulating European imperialism. While less formal, the emerging American overseas empire had its origins in the Caribbean, where the McKinley Administration used civil unrest in Cuba as a pretext to declare war on Spain.

Following the short but sharp Spanish-American War (1898), the United States controlled most of the Caribbean, along with new Pacific territories, through direct and indirect means.

Fast forward to the early 21st Century. The Caribbean has once again become a theatre of imperial ambitions, with the United States facing a challenge from China this time around. This challenge appears in various forms.

First, China has deepened official ties with the region through various multilateral institutions, including the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) — a regional bloc that includes neither Canada nor the United States and with which China has held forums — and the Organization of American States (OAS), whose most recent summit China attended as an observer.

One sign of this growing significance is the personal attention and presence of senior Chinese leaders. Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted Caribbean leaders in January 2015 as part of the China-CELAC summit and visited Cuba in 2014 and 2018. Overall, Xi has visited Latin America three times in the last four years.

Compare this to U.S. President Donald Trump, who has yet to visit the Caribbean or Latin America. In fact, relations between the United States and the Caribbean region continue to sour after Trump’s comments about Haiti as a “shit-hole” country, prompting some Caribbean organizations to declare him persona non grata.

Second, China has actively invested resources in the region under the 1+3+6 framework (one plan, three engines of growth — trade, investment, and financial co-operation — and six industries, namely energy and resources, infrastructure construction, agriculture, manufacturing, scientific and technological innovation and information technologies.)

It has lent money to struggling Caribbean countries, improved their infrastructure and invested in joint ventures while buying more of their products. Case in point: The growing Chinese presence in Guyana, where the recent discovery of oil has encouraged significant Chinese investments.

Third, both sides are investing in soft power tools such as cultural exchanges and language training.

This said, the Caribbean remains an American sea for now. As Evan Ellis of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) says, the United States will continue to play an important security role in the region, because of its geographic proximity and influence on the regional economy. The United States also plays a crucial role in responding to natural disasters, as well as disease outbreaks that strike the region, thanks to its tropical climate.

Finally, the region is a hub of criminal activities — shady financial dealings, drugs and human trafficking — that will continue to draw the attention of Washington, partly because Americans contribute to them.

“In this way, the United States is thus both a principal driver of the region’s security challenges, as well as its principal source of trade, investment and other resources to fight those challenges,” Ellis writes in a paper titled “Strategic Insights: Caribbean Security Issues.”

He also draws attention to the region’s larger deficits.

The region’s small governments, limited resources and fragile institutions “make it susceptible to the corrupting influences of transnational criminal organizations and the initiatives of larger states with an interest in its affairs, including the United States, China and Russia, among others,” he writes.

China appears eager to exploit these conditions.

3. Governance

Let us first acknowledge the following facts. If we take the full members of CARICOM as starting point, about 60 per cent according to the CIA World Factbook) live in one of the worst-run countries in the world — Haiti.

The regional picture does not get any better when we include Cuba (the largest Caribbean country by population, with 11 million) and the Dominican Republic (the second-largest Caribbean country by population with nearly 11 million). While Cuba has recently launched reforms to liberalize its society and economy following the Castro era, it remains a one-party Communist state that continues to repress political liberties, earning it the status of “not free” from Freedom House, an independent watchdog that advocates for freedom and democracy around the world.

The Dominican Republic, meanwhile, has a history of holding what Freedom House calls “regular elections that are relatively free,” while suffering from other malaises. They include “pervasive” corruption and politically motivated violence, such as the recent murder of a prominent lawyer who was exposing a corruption scandal. Not surprisingly, Freedom House considers the Dominican Republic “partly free.” It is also the case for its neighbour, Haiti, which has had a long, sad history of coups and political violence, most recently in early July 2018, when public anger over rising gas prices triggered deadly violence, deepening Haiti’s political instability.

While Haiti might be an outlier, it draws attention to a pervasive problem in the region: violent crime.

Political theory insists that effective governance depends on a stable security environment, yet we know the region suffers from a high homicide rate. This phenomenon affects not only places such as Haiti, which makes headlines for all the wrong reasons, but also vacation destinations in the English-speaking Caribbean.

Consider the following: The U.S. Virgin Islands and Jamaica respectively rank fourth and fifth among countries with the highest murder rates (52.6 and 43.2 murders a year per 100,000 population), as measured by the United Nations’ Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Figures from Belize (7th, 34.4 murders), St. Kitts and Nevis (9th, 33.6), Trinidad and Tobago (11th, 30.9), Bahamas (12th, 29.8), Anguilla (13th, 27.7), St. Vincent and the Grenadines (16th, 25.6), St. Lucia (17th, 21.6), Montserrat (18th, 20.4), and Guyana (20th, 19.4) underscore this regional problem, which not only undermines its reputation, but also costs precious resources.

A 2007 UNODC report suggests that reducing the homicide rate in the Caribbean by one-third could double the rate of the region’s per capita economic growth.

Local authorities know this and have gone through some effort to combat the primary source of this violence — the intra-regional illicit drug trade, with Jamaica being one of its epicentres.

According to the U.S. State Department, Jamaica remains the Caribbean’s largest source of marijuana for the United States and other Caribbean nations, as well as a transit point for cocaine trafficked from South America, because of its location, but also because of its struggling economy and inefficient institutions.

As the State Department notes, organized crime structures have increasingly infiltrated legitimate political, economic and social institutions, thereby undermining their effectiveness and legitimacy.

Regional governance mirrors these internal weaknesses. As Wendy Grenada, an expert on Caribbean politics, wrote in a 2012 paper: “Despite the fact that most Caribbean countries are sovereign independent states, external forces heavily influence decision-making.” Her recommendation? Pooling political power through regionalization, which she considers imperative.

Efforts to deepen and improve governance through CARICOM have yielded some results, but more needs to be done. She also highlights the negative effects of the region’s adversarial political culture within member states.

Not only does it alienate citizens at home, it also does not lend itself to regional co-operation among political elites.

Narrow partisan interests, accordingly, undermine efforts at regional integration.

4. Poverty and inequality and progress

By many social measures, some (but not all) parts of the Caribbean have done well for themselves since decolonization started in earnest during the 1960s and 1970s.

Per capita incomes have risen, with most Caribbean countries now in the top 25 per cent of all emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs).

Median life expectancy hovers around 73 years, compared with 70 years for other emerging market and developing economies, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Infant mortality rates appear relatively low, with female labour force participation reaching relatively high rates. Poverty rates are comparable to other EMDEs.

Yet we must weigh these findings against larger trends and treat them with considerable conceptual care, as a 2016 report from the Caribbean Development Bank, titled The Changing Nature of Poverty and Inequality in the Caribbean: New Issues, New Solutions, finds.

“Despite significant progress in real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita since the 1980s, poverty and inequality remain pressing concerns in the [region],” it reports.

Based on the existing data, Haiti is the poorest nation in the Caribbean with almost 60 per cent of the population considered poor, followed by Suriname (47.23 per cent), and Belize (41.3 per cent). Grenada (37.7 per cent) and Guyana (36.1 per cent) round out the Top 5. Notably, many of the smaller island nations have poverty rates in the high 20s, low 30s with the Cayman Islands (2 per cent) appearing as the major exception.

Larger Caribbean nations, by contrast, have lower rates and can actually boast of having reduced poverty in significant ways. Key examples include Jamaica and Guyana.

In Jamaica, for example, governments can look back on a history of concerted national efforts to reduce poverty through a series of dedicated programs, of which perhaps the most significant is the National Poverty Eradication Program. Jamaica has also been able to make gains in reducing corruption, an obstacle to economic development.

At this stage, it is important to note, though, that definitions of poverty vary and that benchmark standards of poverty say little about the social nature of poverty in the region.

But if we accept the theory that poverty is a lack of capabilities, as Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen defines the concept, it is clear that the Caribbean has more work to do. While regional governments “have invested significantly in improving access to health care, education, water and sanitation” in showing progress, “significant gaps” remain, as the Caribbean Development Bank notes in its report.

Worse, the capabilities that exist are not equally accessible. This inequality of opportunity means that poor individuals can’t access the capabilities that could allow them to escape their poverty.

As the Caribbean Bank report notes, the terms poverty and inequality remain liable to be used interchangeably. “However, poverty and inequality are not the same, but rising levels of inequality are bad for poverty reduction and economic growth.”

In short, the Caribbean not only requires more investments in public goods, but a more equal distribution of the same.

5. Corruption

When it comes to corruption, the Caribbean appears on the map as a sea of red — the colour with which Transparency International, a non-governmental organization, identifies countries with high levels of perceived corruption in its annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). But the region also features some bright spots.

The region’s least-corrupt country, according to Transparency International, is the former British colony of Barbados. With a population of slightly more than 290,000 people who enjoy one of the highest per capita gross domestic products in the region, Barbados ranks 25th in the 2017 edition of the CPI.

This ranking places this eastern Caribbean island just behind G7 member and European Union (EU) co-founder, France (tied for 23rd with Uruguay) and ahead of several other EU members, including another G7 member and EU co-founder, Italy (54th, tied with sub-Saharan Mauritius and post-communist Slovakia).

The Bahamas, which sits second among the Caribbean countries at 28th, St. Vincent and the Grenadines (40th), Dominica (42nd), St. Lucia (48th) and Grenada (52nd) also rank ahead of Italy.

Caribbean countries are also capable of making progress. Consider Jamaica. In 2009, it ranked 99th. In 2017, it had improved to 68th, although this improvement has seen some ups and downs.

But this positive picture requires perspective. These case studies reflect relatively prosperous countries whose populations are as small as the islands they occupy. In some ways, they are the Switzerlands or Luxembourgs of the Caribbean.

The statistics are less encouraging when we look beyond them and consider the three most populous Caribbean countries: Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Cuba ranks 62nd, the Dominican Republic 135th and Haiti 157th (tied with Burundi, Uzbekistan and Zimbabwe, each of them political basketcases in their own ways.)

These conditions, of course, did not appear overnight and their causes are manifold. Various scholars have argued that corrupt societies are also deeply unequal societies. Jong-Sung You and Sanjeev Khagram claim in their analysis that inequality normalizes abuse of public power for private gain. The more unequal a society, the more likely individuals are to game the system to sustain themselves and their clients. This behaviour, however, only worsens inequality by funnelling resources away from institutions (courts, police, administrative bureaucracies) designed to benefit the public.

Deprived of resources, they become increasingly ineffective, while appearing biased towards those who control them. Accordingly, they start to lose their legitimacy, thereby making it more likely for individuals to ignore them. In short, corruption and inequality reinforce each other, a vicious circle that generally knows only one category of winners: A small number of elites who manage to seize the wealth of any society to the detriment of the rest.

Not surprisingly, Haiti, one of the most corrupt countries in the world, is not just one of the poorest countries, it also ranks among the most unequal (fourth overall) as measured by the Gini Index (a statistical measure of economic equality developed by Italian statistician Corrado Gini in 1912.)

Other factors have also shaped corruption levels in the Caribbean. In their research, You and Khagram point towards the close relationship between colonial experiences and corruption. They note that former British colonies, with their imported common-law systems, tend to be “significantly less corrupt” than the colonies of other European powers. The Caribbean underscores this theory. All of the five least-corrupt Caribbean states were former British colonies.

6. Environment

The invaders that stormed Montesinos Beach in the Dominican Republic capital of Santo Domingo in July 2018 carried neither weapons nor the insignia of some foreign power from a distant shore.

They did not step out of a landing boat or drop out of the sky after a preparatory bombardment. They instead sloshed and swished their way on land — mountains upon mountains of water-soaked garbage, moving across previously pristine beaches.

No one knows exactly how many pieces of garbage crawled their way out of water, but footage shows men wading up to their knees through a frothy mixture of salt water, seaweed and every imaginable piece of flotsam and jetsam as they waged a desperate defensive battle to clean up their country’s most important economic asset — its environmental reputation as a paradise destination.

While authorities collected 60 tonnes of garbage, they are likely waging a losing war, for the figure represents only the share that workers could collect.

They could not clean up the toxins that seeped into the ground, nor they can prevent this pile-up from happening again — at least until authorities have brought about a radical change in environmental attitudes and actions.

“Everybody uses the rivers and the beaches as dump sites,” Cyrill Gutsch, founder of Parley for the Oceans, an environmental organization, told The New York Times.

While most of this garbage drifts into the open ocean, the share that bounces back is sufficient to cause damaging headlines, not to mention harming entire ecosystems.

“It happens pretty much all the time if there is a strong rainfall or storm,” said Gutsch. Unfortunately, available evidence predicts that the intensity, duration and frequency of such extreme weather events will only increase, thanks to a larger environmental threat darkening Caribbean skies: Climate change.

Like elsewhere, climate change will mean more tropical storms, such as Irma and Maria, that killed thousands across the region and caused hundreds of billions of dollars in economic losses by damaging local homes and infrastructure while discouraging foreign visitors. Like other parts of the developing world, the Caribbean can also take cold comfort in the fact that it has contributed little to the problem. This limited liability for climate change, of course, does not free the region of its effects, which will exceed those elsewhere, as the region ranks among the world’s most vulnerable.

Haiti tops GermanWatch’s 2016 Climate Risk Index, which also identifies the Dominican Republic as one of the most-at-risk countries.

Local, regional and international efforts to raise the Caribbean’s resilience to climate change have been under way for some time. They include, among others, the 2002 creation of the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre as the agency co-ordinating the region’s response to climate change.

7. Tourism

It was about a year ago in September that the deadly duo of Category 5 hurricanes — Irma and Maria — cut across Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and other Caribbean nations such as Dominica and Antigua and Barbuda, leaving behind death and destruction.

The storms also underscored the dependence of the region on tourism — the most important driver of economic growth and the primary source of foreign currency.

According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), the Caribbean ranks as the most tourism-intensive region in the world.

While travel and tourism generate about 15 per cent of the Caribbean’s economy, several countries have shares above 30 per cent, with more than 60 per cent in the case of Antigua and Barbuda, according to 2016 figures. More recent research from the WTTC shows that the Caribbean accounts for 11 out of the 20 countries that rely the most on tourism.

This reality makes Caribbean economies especially “vulnerable to the vagaries” of the effects of weather, as a 2017 UNESCO report says. According to a 2013 study by the International Monetary Fund, most CARICOM members have at least a 10-per-cent chance of being struck by a hurricane and even a moderate storm can reduce gross domestic growth by 0.5 per cent.

It is against this backdrop that the 2017 hurricane season could well have been a defining moment for the tourism industry in the region — and not in a good way.

According to WTTC, just under a million fewer tourists visited the Caribbean following hurricanes Irma and Maria, costing the region more than $700 million US. Other sources peg the economic damage even higher.

According to the Caribbean Tourism Organization, the Caribbean lost more than $1 billion in tourism revenues and recovery efforts could cost close to $6 billion.

This wide range, however, also alerts to the uncertainty that remains, as the situation in the British Virgin Islands perhaps best illustrates.

It depends on tourism like no other Caribbean nation. According to WTTC, nearly 84 per cent of all jobs and 96 per cent of GDP depend directly or indirectly on tourism and travel.

Recovery from Hurricane Irma continues, with evidence of its destructiveness plainly visible to everybody. At the same time, tourists have already started to return, apparently undeterred. Reports from other affected islands offer comparable accounts.

The tourism industry on St. Martin — whose northern half belongs to France, its southern half to the Netherlands — remains in recovery mode, yet as The New York Times found out, “visitors seeking sun, sand, solitude will find all 37 of the island’s stunning beaches open, the roads clear of wreckage and locals as welcoming as ever.”

In fact, operators, far from being financially shy, have started to offer new activities to draw tourists.

As hotelier Marc Petrelluzzi told the newspaper, hurricanes can only do so much damage. “There are just some things that the hurricane just couldn’t take away,” he said. “It’s the view. It’s the sea. It’s the beaches. It’s the vegetation. It’s nature.”

8. Migration

Migration — voluntary or otherwise — has and continues to shape the Caribbean basin, “home to some of the most complex interactions in recent history among previously diverged human populations,” according to a 2013 article in PLoS Genetics. This history appears in the diverse faces and genes of Caribbean populations, first and foremost a genetic composite of European, African and indigenous influences that reflect the region’s history of European colonialism starting in the late 15th Century and its part in the transatlantic slave trade that did not end until the late 19th Century.

Others have only added to this diversity. Starting in the early 1800s, the first indentured workers from China arrived in Trinidad and other British possessions as substitutes for emancipated slaves. In the late 1830s, indentured workers from the British Raj in India also arrived in the region, with some bringing along their Muslim religion. Christians from the Middle East (modern-day Syria and Lebanon) deepened the region’s diversity in the late 1800s.

Note that this is a general look as we cannot accurately capture the migratory streams that have contributed to the unique demographics of each Caribbean nation. Among Cubans, whom the authors of the PLoS Genetics piece studied, the share of West African ancestry ranged from 2 per cent to 78 per cent. Among Haitians, the average largest portion of West African ancestry was 84 per cent. Accordingly, Haiti’s population is largely black, while Cuba’s population is more mixed. In Trinidad and Tobago, almost 36 per cent of the population qualifies as East Indian.

“Due to its enormous geographic and demographic diversity, the Caribbean is a challenging region to study when focusing on migration,” according to a 2017 working paper on the region from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

But despite this diversity, migration continues to link the region.

“The Caribbean is a region of origin, transit and destination of extra-regional and intra-regional migration flows, and experiences considerable return migration,” the 2017 IOM paper continues.

Thanks to its location between North and South America, the Caribbean serves as a transit point for irregular migrants from South America and elsewhere trying to reach the United States, which attracts large numbers of Caribbean migrants, legal and otherwise. Canada also has, and continues to attract, Caribbean migrants. Between 1996 and 2001, the number of Canadian residents who reported Caribbean origins rose 11 per cent, with the majority of Canada’s Caribbean population being born outside the country.

According to the 2016 census, almost 750,000 people reported Caribbean origins — or 2.1 per cent of the population with sizable Jamaican and Haitian pockets in Toronto and Montreal respectively.

Migratory patterns reflect familiar push and pull factors. They include the search for economic opportunities in the developed world, often depriving Caribbean countries of their best and brightest, and natural disasters such as the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti.

The IMO also anticipates that climate change will be a factor.

“Caribbean islands are especially vulnerable to extreme weather events and global climate change — events and processes that can cause internal displacement and set in motion emigration processes,” it states.

Overall, the Caribbean remains a source of net migration, and the ongoing influx of refugee seekers from Haiti by way of the United States shows that these flows will continue to touch Canada.

9. Minorities

It is hard to overstate the diversity of the Caribbean. It consists of countries with fewer than 100,000 people and three countries with at least 10 million people (Cuba, Dominican Republic and Haiti). It consists of small and large islands, and inland territories. Some Caribbean countries are incredibly wealthy. Others rank among the poorest in the world. Such wide economic margins also exist among their respective populations. A range of ethnicities, languages, religious beliefs and government forms complete this Caribbean kaleidoscope.

This diversity also creates plenty of social frictions and political cleavages.

The state of relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic is a case in point. Both countries, of course, share the island of Hispaniola, but they are not exactly best neighbours over the status of Haitian migrants living and working in the more prosperous Dominican Republic.

Haitians have historically supplied cheap labour in the Dominican Republic, first in its sugar cane industry, then in services. But this flow of labour from impoverished Haiti to the relatively prosperous Dominican Republic has been a source of tension after various agreements between the two countries lapsed in 1986 following the collapse of Haitian president Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s dictatorship.

As Maria Cristina Fumagalli, author of On Edge, Writing the Border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic notes, the unauthorized status of Haitian immigrants has exposed them to human rights abuses, including discrimination in access to education and health services. Nationalist forces in the Dominican Republic have also used Haitian migrants to stoke xenophobic sentiments to distract from domestic problems, according to Fumagalli.

Relations between the countries reached a low point in 2013 when the Dominican Republic revoked the citizenship of those born after 1929 for immigrants without proper documentation, even though the constitution at the time automatically granted citizenship to children born in the Dominican Republic.

This retroactive decision stripped 133,000 Dominicans of their citizenship, most of them people of Haitian descent, whose relatives had come to the Dominican Republic, as far back as the 1890s.

The Dominican Republic has since partially reversed course, but relations have remained cool and actually worsened in the spring of 2018 when the army sent soldiers and drones to the border, even after officials had found no significant influx of Haitians over the past five years, based on 2017 figures.

Elsewhere in the Caribbean, sexual minorities have found themselves the objects of discrimination.

While Trinidad and Tobago, in April 2018, joined the Bahamas and Belize as the third country in the English-speaking Caribbean to repeal laws that criminalized consensual sex between adults of the same gender, LGBTQ activists in the region note that much more work remains against the backdrop of discriminatory laws that often date back to the colonial period.

Of particular interest will be developments in Cuba, whose Communist government has had a long, brutal history of discriminating against sexual minorities following the revolution of 1959.

This said, Cuba has taken considerable steps to reform its laws and attitudes towards sexual minorities, with more legislative reforms likely on the way as the country revises its Soviet-era constitution.

This political change also has a personal dimension. Under Fidel Castro, the Cuban government maintained re-education camps. In 2010, Castro admitted personal responsibility for such policies. His niece, Mariela Castro, is now actively lobbying for gay rights.

10. Post-colonialism

Paulette Wilson arrived in Britain from Jamaica in 1968, when she was 10 years old, as a young member of the Windrush generation, the group of Caribbean immigrants, who reached Britain between 1948 and 1971 to help rebuild after the Second World War.

Wilson — like so many others — soon grew to know no other home. She worked steadily as an adult.

She raised a daughter, then helped to raise her granddaughter. Yet in 2015, she received a letter informing her that she was an illegal immigrant and in late November, Wilson escaped extradition to Jamaica at the last minute thanks to an intervention by her local MP.

Wilson’s personal story soon exposed a larger political tale of administrative cruelty and deliberate negligence at the highest political echelons that some say sought to diminish the contributions of Caribbean immigrants to British society — a form of post-colonial arrogance.

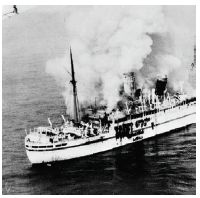

When the first Caribbean migrants disembarked from the MV Empire Windrush in 1948, they were still colonial subjects, but eagerly needed. When this program ended in 1971, against the backdrop of rising racism (see Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech in 1968) and economic stagnation, the British government granted all Commonwealth citizens permanent residency.

But through a combination of administrative oversight and personal neglect, many Caribbean migrants never received proper documentation. These circumstances came back to haunt countless individuals, such as Wilson, in 2012 when Theresa May, then home office secretary, now prime minister, gave a speech in which she promised a “hostile environment for illegal migration.“

Wilson and others like her soon found themselves denied health services, and subject to deportation, even though they had lived in Britain for decades. Worse, the British government continued to treat Caribbean migrants in this manner, even as authorities became aware.

A government report known as Chasing Status, published in October 2014 when May served as home secretary, alerted government officials to the issue and urged action. Nothing happened.

The British diplomatic corps also became aware of the problem as early as 2013 and a Caribbean foreign minister raised the issue with then-foreign secretary Philip Hammond in 2014 and more formally in 2016, during the biannual U.K.-Caribbean forum — to little effect.

The issue broke in full public view when The Guardian newspaper used Wilson’s story as the touch-off point for a larger investigation that exposed additional wrongdoing, forcing the resignation of Amber Rudd, May’s successor as home office secretary and political ally.

Days before Rudd’s resignation, May publicly apologized to 12 Caribbean heads of state, but the scandal continues to burden relations between Britain, the English-speaking Caribbean and British people of Caribbean descent.

Andrea Stuart, a prominent Barbadian-British historian, quotes her mother: “Another debacle. Do we really have to remind Britain again and again that the glorious buildings, the museums with the priceless artifacts, the cathedrals, the great wealth of the city, have been built on black backs? It is as if the generations after generations of slaves toiling in the cane fields of the Caribbean never happened.”

David Olusoga, the author of Black and British: A Forgotten History, recently wrote that outrage over the Windrush scandal has created a convenient mythology with the plucky, industrious Caribbean immigrants on one side, a hostile bureaucracy on the other side.

In reality, he writes, British society has always struggled to reconcile its colonial legacy and bitter attitudes towards immigration.

The “hostile environment” that trapped the Windrush generation, with its “vindictiveness and indifference,” will remain in place, he writes. “Other groups, for whom less sympathy exists, or is likely to develop, will remain its targets.”

Wolfgang Depner holds a doctorate from the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, where he previously taught political philosophy and international relations, among other subjects for several years. He currently lives and writes in Victoria, B.C., where he teaches at Royal Roads University.