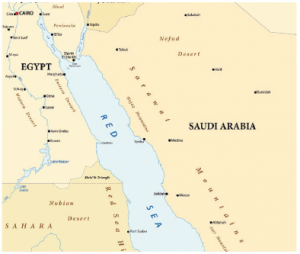

At the end of July, two very large crude oil tankers from Saudi Arabia were attacked with anti-ship missiles by Yemeni rebels from the eastern shore of the Red Sea, just north of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. One of the tankers was damaged slightly in the stern.

As a result, the Saudi government ordered a temporary halt to Saudi tankers travelling through the Red Sea from its Persian Gulf oil terminal to the SUMED (Suez-Mediterranean) pipeline terminal in Egypt. Reportedly, there are plans to have naval convoys join such tankers and other commercial vessels passing through the narrow southern portion of the Red Sea between the coast of Yemen and the port city of Djibouti. There had also been media reports of missile attacks against passing tankers in April and May — after Houthi militias threatened to attack oil tankers passing through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. The Houthis are an armed Islamic political movement controlling the northern regions in the Yemeni war.

Global trade through the Red Sea

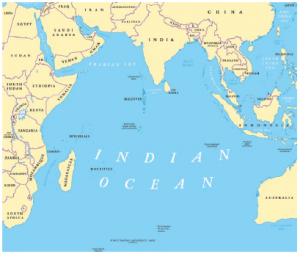

The Red Sea — with the Suez Canal at the north end and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait at its southern mouth — is one of the most important trade routes from the Middle East and the Persian Gulf to Europe, particularly for oil tankers. Through this major global transit route, petroleum and refined oil products from the Middle East and the Persian Gulf, as well as manufactured goods from South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, transit to Europe and on to North America. At its southern end, between Djibouti and Yemen, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait is only about 30 kilometres wide.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, an estimated 4.8 million barrels of crude oil per day as well as refined petroleum products passed through the Red Sea in 2016. But the Suez Canal is too shallow for a completely full supertanker carrying approximately two million barrels of oil.

Instead, the procedure is to offload half that amount via the SUMED pipeline in Egypt before travelling through the Suez Canal. Smaller oil tankers do take on crude oil at the Saudi East-West Pipeline terminal at the Saudi port of Yanbu al-Bahr on the eastern coast or from the Bashayer Marine Terminal on the western coast — located about 25 kilometres south of Port Sudan — where Sudan’s two main export pipelines converge to reach the coast. The Suez Canal is being enlarged to permit larger vessels to transit between the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea.

Currently, it is estimated that between 12.5 per cent and 20 per cent of total global trade and about 2.5 per cent of global oil cargo passes through the Red Sea area. And China alone sends up to $1 trillion US in goods through the Red Sea area annually. By comparison, the amount of goods moving though the South China Sea is estimated at about 30 per cent of global trade — about $5 trillion US in value. While trade through the Red Sea is less significant than trade going through the South China Sea, it is still very substantial, impacting Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

China’s interest in Djibouti

Since the 1990s, the Chinese government in Beijing has been pursuing a mixed “great power” strategy of economic engagement and military outreach to Africa.

Commercially, Beijing encouraged Chinese construction companies and financial lenders to go global as part of the country’s efforts to acquire greater access to natural resources — minerals, oil and food supplies — by doing more business overseas. Similarly, Chinese port management companies have contracted to handle African ports with high-volume turnover.

China’s growing economic power can be seen in its presence in the tiny but strategic port country of Djibouti. Here, on the tip of the Horn of Africa, China has demonstrated a vital portion of its strategically planned Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), foreign direct investment and overseas defence spending — all of which will increase its influence abroad, both in hard and soft power. Its BRI infrastructure projects seek to revive historical overland and maritime trade routes through a massive rail and maritime network that is made up of $1 trillion US in investments across Asia and Europe. Djibouti has become the western point of President Xi Jinping’s BRI and a key entry point for Chinese economic and commercial interests in Africa.

China has pursued a number of BRI projects in Djibouti. The largest is the $590-million US Doraleh Multipurpose Port funded by a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China. This new port facility west of the Port of Djibouti has terminals for handling oil, bulk cargo and containers — all of which have direct access to the new Addis Ababa-Djibouti Electric Railway, which provides landlocked Ethiopia with railroad access to the Red Sea and which also secured its funding through a loan from the Export-Import Bank. And there are plans for a natural gas pipeline from the port up to the Ethiopian highlands, to be funded by a BRI loan.

Meanwhile, China’s ambitious BRI mega-projects elsewhere in Southeast Asia have incurred high price tags, leading to heavy debt loads. Observers have warned of “debt traps” and have called China a “predatory lender.”

China’s military presence in the region began with the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) anti-piracy patrols off the Horn of Africa, in the Gulf of Aden and on the Somali coast in 2008. Participating in these United Nations counter-piracy activities has boosted PLAN’s ability to convoy Chinese oil tankers and commercial vessels through these far seas and to deploy and improve PLAN expeditionary naval forces along international routes deemed vital to China’s economic and energy requirements.

In addition, China has deployed 2,000 People’s Liberation Army peacekeepers to African operations in South Sudan and Darfur as well as Mali in West Africa and it currently contributes more than 10 per cent of the UN peacekeeping budget. These UN deployments improve its capacity to conduct “military operations other than war” and to train and test its military troops and equipment in Africa and elsewhere.

Beside the Doraleh Multipurpose Port, China and the Djibouti government have negotiated a “strategic support base” (a military base by another name) to stage, support and re-supply PLAN anti-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden and nearby PLA peacekeeping operations — as well as humanitarian activities.

Opened in August 2017, the PLAN Djibouti Support Base received a brigade of PLAN marines and six armoured personnel carriers, with the first live-fire exercises the following month. In May 2018, construction began on a large-scale pier — estimated at more than 330 metres in length — on the harbour side of the base. The Chinese military base is only a few kilometres from the American, French and Japanese bases in Djibouti. The U.S. base, Camp Lemonnier, is the only permanent American military facility on the African continent and acts as a hub for U.S. counter-terror operations.

This closeness has led to concerns about possible friction or even confrontations between the foreign military forces. In recent months, American military pilots flying near or to the U.S. base have complained that laser beams have been directed at their aircraft cockpits from the vicinity of the Chinese base — though Chinese authorities have denied such dangerous activities.

Interestingly, a Chinese action war film, Operation Red Sea, directed by Dante Lam, was released in January 2018 and is currently the second highest-grossing Chinese-produced movie. The nationalistic film is loosely based on the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy’s evacuation of 225 foreign nationals and nearly 600 Chinese citizens from Yemen’s southern port of Aden during late March in the 2015 period of the war in Yemen. At the time, Chinese naval frigates conducting anti-piracy patrols off the coast of Somalia were diverted to Aden to evacuate people trapped by the fighting. The evacuees were taken by the PLAN frigates across the Red Sea to Djibouti, where they were flown to their home countries. The Chinese ministry of defence has stated that this was the first time its PLAN had evacuated foreigners from a war zone.

Since March 2015, a war has raged in Yemen. A Saudi Arabian-led military coalition of nine African and Middle Eastern countries in support of the recognized Yemeni government has been bombing the Houthi rebels, reportedly supplied covertly by Iran, despite United Nations sanctions. In addition, the Saudi coalition has attempted to maintain a coastal blockade as well as launching ground assaults. Even so, the United Nations has attributed most of the estimated 9,500 civilian deaths to airstrikes as well as malnutrition and disease.

In June, the Saudi coalition, including United Arab Emirates, launched a ground assault to seize the rebel-held Port of Hodeida on the Red Sea — and subsequently Hodeida city and airport. But the assault could prove catastrophic. An estimated 80 per cent of Yemen’s food supplies and medicines for the 22 million Yemenis displaced by the fighting are arriving through this port, according to Jens Laerke of the UN Organization for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. He also pointed out that fuel and other essential humanitarian relief also arrive via the port. UN officials have called for a ceasefire and are working for a negotiated truce to halt the humanitarian crisis.

Partly in response, Houthi forces have launched surface-to-surface missile strikes — or possibly heavy artillery rockets — into Saudi Arabia and against Saudi coastal targets along the Red Sea. In the coastal zone reside such necessities as the Saudi Petroline oil terminal, desalination plants, cement plants and industrial infrastructure. There are also residential areas along this coast.

An additional nine desalination plants are to be constructed along the coastline and they could also be targeted in the future. The Saudi Arabian News Agency has reported that Saudi Patriot anti-missile systems have shot down a number of such missiles targeting the Saudi Red Sea coastline — with some reportedly supplied covertly by Iran.

Across the Red Sea, the Sudanese oil terminal at Bashayer Marine Terminal — where its two north-south pipelines link up to meet oil tankers for seaborne transit — could also become a tempting missile target as Sudanese armed forces are fighting as part of the anti-Houthi coalition.

Towards stability and demilitarization

The Horn of Africa has a centuries-long history of interregional trade and conflict to ensure state survival among the countries and territories that extend along the Red Sea, including Egypt and Sudan to the north, Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula to the east and Somalia to the south.

After decades of foreign economic and military involvement in the Horn of Africa by a variety of state and commercial actors, China may have become the “new policeman on the block” to protect its own economic interests there in the years ahead. Despite the current trade war between China and the U.S., Chinese exports continue to surge worldwide, with growing commercial engagement in African countries as well as partnerships in infrastructure development. Whether the China-U.S. trade friction leads to a stalemate or a possible negotiated “truce,” President Xi BRI-generated projects will further China’s engagement in Africa.

In a speech in April, at the PLAN naval review in the South China Sea, Xi announced plans to build a “world-class navy under the banner of the Chinese Communist Party.” Towards this goal, China has already refurbished a former Soviet-era aircraft carrier — acquired from Ukraine — that is now operational as the CNS Liaoning. In addition, its second, but first homegrown carrier, named CNS Shandong, according to the mainland Chinese media, completed its maiden sea trials in May with follow-up sea trials having begun in September. In addition, there are media reports that China may attempt to “quietly” build as many as seven carriers by 2025 — rather than the currently projected total of four.

With its PLAN base now operational in Djibouti, foreign observers repeatedly suggest that China will set up a similar overseas naval base near the Pakistani port of Gwadar — the Indian Ocean end of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

In addition to a decade of PLAN anti-piracy patrols around the Horn of Africa, a three-ship PLAN task force in 2015 completed an around-the-world circumnavigation. And in October 2017, another three-ship PLAN fleet unit joined Russian Federation warships in the Baltic Sea for joint naval exercises.

And, interestingly, the Royal Canadian Navy frigate HMCS Vancouver made a six-day port call in Hong Kong in May — where it held joint interoperative exercises with Chinese PLAN naval ships. After the joint exercises, HMCS Vancouver left to join the annual United States Navy’s multi-country RIMPAC exercises off Hawaii and shore activities in July. The Chinese navy had been invited to participate in RIMPAC, but the invitation was “withdrawn” after the extensive Chinese “island building“ in the South China Sea, with placement of weapons systems, including missiles, on the new “islets,” though it is believed that a PLAN warship and/or submarine was assigned to stealthily observe the RIMPAC exercises in the mid-Pacific.

As more Chinese PLAN warships complete trans-oceanic patrols in the “far seas,” it may not be that long before one of China’s new aircraft carriers will be crossing the Indian Ocean and anchoring in the harbour of Djibouti in eastern Africa.

Robert D’A. Henderson currently does international assessments and international elections monitoring. Previously, he taught international relations at universities in Canada and overseas.