Three books explore aspects of the liberal world order that today is being challenged — two in the context of Canadian diplomacy and defence, a third from the perspective of one of the U.S.’s most experienced and respected politicians.

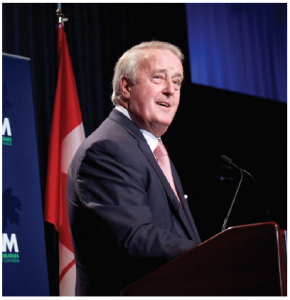

When he won election in 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared to the world that Canada was “back.” Back to what? The “golden age” of Canadian diplomacy that followed the Second World War? That period is often viewed as the apogee of this country’s foreign policy. But in Master of Persuasion: Brian Mulroney’s Global Legacy (Signal, McClelland & Stewart, $35), Fen Osler Hampson makes the case that Canada’s global golden age actually occurred under Brian Mulroney.

To be sure, this doesn’t dovetail with the views many Canadians hold of Canada’s 18th prime minister. By the time he stepped down to make way for Kim Campbell, Mulroney was so reviled that his Progressive Conservative party was eviscerated in the election that followed.

But consider what Mulroney accomplished for Canada through diplomacy. The Acid Rain Treaty. The Free Trade Agreement with the United States. NAFTA. Leading the international effort to dismantle apartheid. Leading on the ozone crisis. Helping place the environment firmly on the world’s agenda.

But consider what Mulroney accomplished for Canada through diplomacy. The Acid Rain Treaty. The Free Trade Agreement with the United States. NAFTA. Leading the international effort to dismantle apartheid. Leading on the ozone crisis. Helping place the environment firmly on the world’s agenda.

Hampson isn’t content to simply recount Mulroney’s involvement in world affairs; he wants to ensure readers learn from the former prime minister’s successes (and some of his failures, such as his lack of systematic attention to the Asian giants). Each chapter ends with lessons, the overarching one of which is: Personal relationships matter. Canadians who glibly dismiss Mulroney as a snake-charmer and schmoozer, in the back pocket of the Americans, misunderstand just how crucial his political skills and negotiating talent proved in influencing U.S. policy for the good. Even as critics cringed at the palsy-walsy “Shamrock Summit” between Mulroney and Ronald Reagan, the former was already chatting up free trade, a policy from which this country has benefited immeasurably and which, today, it strives to safeguard.

In fact, Mulroney was so respected by the Americans that president George H.W. Bush described him as a member of his inner cabinet. Bush sought Mulroney’s advice on a host of issues — from acid rain (it’s worth remembering that in the mid-1980s, about 10,000 of Eastern Canada’s lakes were deemed acid-damaged) to the 1991 military action that freed Kuwait from Saddam Hussein. At one point, when Margaret Thatcher — well-known for her clashes with Mulroney over South Africa — challenged Canada’s place in the G7, Ronald Reagan responded, “I don’t want to be part of any club that doesn’t include Canada.”

One may argue that Mulroney had an easier time of it with Reagan and Bush Sr. than our current government has with Donald Trump on free trade. But Hampson reminds us that protectionism was on the rise in the U.S. during the 1980s, too, with more than 300 protectionist trade bills before Congress at one point.

The trick for Mulroney was that he was an astute student of American politics who also made it his business to develop and deepen his relationships with powerbrokers. It’s no mystery that he has been a trusted emissary for Justin Trudeau in Washington. He knows Trump personally; his sons are friendly with Ivanka Trump. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross is one of his neighbours in Palm Beach. The Rolodex goes on.

In chapter after chapter, Hampson lays out just how involved, and assertive, Mulroney and his team were — and not just with the Americans. For instance, moved by the heart-wrenching TV coverage by journalist Brian Stewart of the 1984 Ethiopian famine, Mulroney mustered his UN ambassador, Stephen Lewis, and his foreign minister, Joe Clark, to act and lobby the rest of the world to do the same. The UN and others came aboard. Stewart said later that he believed at least 700,000 lives were saved because of Canadian efforts.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Canada also found itself immersed in the breakdown of the Soviet empire, and answered the call for peacekeepers in places as diverse as Bosnia and Somalia. As we know from the Somalia torture scandal, these actions did not always end well. Yet, under Mulroney, Canada showed up. It contributed more than 10 per cent of all troops to UN peacekeeping missions and was active in all 16 missions. These days, our record is somewhat different.

In another episode Hampson underlines, namely the historic reunification of Germany, then-chancellor Helmet Kohl noted that three foreign leaders were key to making it happen: George H.W. Bush, Mikhail Gorbachev and Mulroney, who unequivocally endorsed German unity when other Western leaders were wary. With his influence, he was listened to.

Mulroney’s foreign policy record speaks to tenacity, “laser-like” focus, non-partisanship, the power of relationships and an understanding that political capital is meant to be spent, not just inside our borders, but globally. Mulroney may not have been the most admired politician at home, but Hampson makes a strong case that he deserves much more credit than we give him for the leadership he showed abroad.

Afghanistan’s Operation Medusa

Afghanistan’s Operation Medusa

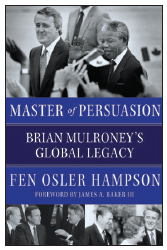

At a time when NATO countries — including Canada — have been targeted by the United States for not pulling their weight, OPERATION MEDUSA: The Furious Battle That Saved Afghanistan From the Taliban (McClelland & Stewart, $32), the story of a milestone battle in the Afghanistan campaign, seems particularly pertinent.

In September 2006, Canadian Maj.-Gen. David Fraser, who co-authored the book with Brian Hanington, commanded the coalition forces in the Panjwayi District of Kandahar province. Although the events he describes occurred 12 years ago, politicians should review them today.

Fraser’s enlightening book shares a military man’s wry wit and admiration for soldiers in combat. Although he invites any impatient reader to skip right to the main battle, don’t. You’ll miss his description of the hard-driving, foul-mouthed tactical commander known as “Mother” who nonetheless delicately sipped his tea using the proper pinky-finger etiquette. You’ll also miss Fraser’s affection for his leadership team, “the Posse,” and his kind words for a Vancouver cop and army reservist named Harjit Sajjan, who laboured undercover in Kandahar. And you’ll miss the first early lesson: How important it was that Fraser had already developed deep contacts within militaries all over the Western world — people whose support he would later draw on in theatre.

Operation Medusa was born as Fraser realized that the Taliban was growing confident of its ability to win in the south of the country. Taliban leaders knew of the Americans’ plans to transfer leadership of the stabilization force, known as ISAF, to NATO, and were eager to challenge it. As commander of Regional Command South based in Kandahar, Fraser bore responsibility for planning and executing a major drive to halt enemy momentum.

The operation, he says, was not meant to be a glorious victory on the battlefield, but to send a signal of strength to the Taliban, and, more practically, to ensure Taliban fighters couldn’t establish a safe base from which to attack Kandahar. His coalition forces succeeded in what was, to that point, the “largest battle fought by Canadian troops since the Korean War.”

But it was not fought without problems. For instance, “our American allies harboured a deep concern that we Canadians were about to enter combat on their behalf without being at all combat ready,” he notes. “I couldn’t disagree. Two decades of peacekeeping cannot prepare an army for classic combat.”

Then there was the realization that NATO leaders in Brussels had assumed “this was going to be a peacekeeping operation.”

Worse problems would mar Medusa itself. To start, Fraser had trouble getting the troops he needed, even days before the battle. On asking what further support he might expect from NATO, he was told only: “Moral.”

Fortunately, he could turn to the U.S. Green Berets at Kandahar Air Base and an experienced U.S. infantry company, which mustered air support: Harriers, fighters, bombers, Black Hawk and Apache helicopters. When the battle began on Sept. 2, 2006 — not quite five years to the anniversary of 9/11 that led to it in the first place — Fraser’s force numbered 2,200.

Still, things started badly. On the first day, a Royal Air Force Nimrod surveillance aircraft crashed near the village of Chil Khlor, killing 14.

There were ambushes, long firefights and more dead. And, proving that even meticulous planning can go south quickly, Fraser discovered abruptly that the operation was running out of ammunition.

“So there we were, about to face a deeply dug-in enemy armed to the teeth in what was going to be the fight of our lives, with 20 minutes worth of ammunition left for the turret guns in our LAV IIIs, the vehicles that would be leading the charge. [Expletive]” In the nick of time, new ammo arrived, from New Zealand.

Meanwhile, a pilot accidentally fired on Canadian soldiers, killing one and wounding 30. A disoriented Chinook pilot set down beside a Taliban position, but got out unscathed. Said one of Fraser’s tactical commanders, “We just agreed it was going to be [expletive] Armageddon every day.”

But this mixed bag of troops, including the Green Berets, slowly took and held ground, and the Taliban death toll ballooned. After two weeks, Fraser’s forces had met Operation Medusa’s goal.

What did he learn? That each allied country had a different idea of what its mission in Afghanistan was. That resources between them were uneven. That, during Operation Medusa at least, “many nations simply would not show up to fight at all.

“Planning was agony. Even when the operation was only days away, we weren’t certain who would support us at H-hour… they were decisions of the moment, presumably made in national capitals by people with no idea of the stakes.”

Warfare by committee, then. Still, the experience in Panjwayi District showed — contrary, perhaps, to the ill-informed impressions of today’s U.S. president — that Canada was and is willing to do its part. Canadians work well with the American military. Thanks to Afghanistan, Canada now boasts a battle-hardened military. It needs no lectures from anyone.

John McCain’s farewell in print

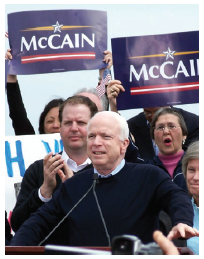

Told that brain cancer would soon claim his life, U.S. Republican Senator John McCain wrote a book completely bereft of self-pity. Instead, The Restless Wave: Good Times, Just Causes, Great Fights, and Other Appreciations (Simon & Schuster, $40) focuses entirely on the legacy and future of the country he so cherished and fought for in wartime. Not all readers will share McCain’s unwavering patriotism — but his rallying call is for a better United States, based on enduring values any decent person would endorse.

For McCain, who died in August, just three months after the book was released, was the kind of statesman the U.S. is also capable of producing. Example: Though he lost the 2008 presidential contest to Barack Obama, he nonetheless went out of his way to ensure race was not used as an election tool by the Republicans. “I recognized the social progress Obama’s candidacy represented, and I didn’t want to impede it by inciting, even with a wink and a nod here and there or with language that had double meanings, the prejudices that have marred our history,” he wrote. At one rally, “an otherwise polite supporter expressed her concern that Obama couldn’t be trusted because he was an Arab. I took the microphone from her. ‘No, ma’am,’ I corrected her. ‘He’s a decent family man and citizen whom I happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues. That’s what elections are for.’”

One can’t help but contrast that with the bias-baiting 2016 race, in which immigrants were denounced, walls were pledged and “Lock Her Up” became a rallying cry.

In contrast, McCain is generous about his political foes. Hillary Clinton, whom he knew well as a senator, is “very warm, engaging, and considerate in person, and fun.” George W. Bush is “likable, and a good man.” Obama, whose foreign policy McCain would frequently criticize, is nonetheless “an intelligent man, reasonable and cautious.” And McCain often worked closely alongside Democratic senator Ted Kennedy on issues of mutual passion, such as immigration reform.

Obama doesn’t get off scot-free, however. McCain believed he utterly mishandled U.S. foreign policy despite good intentions. Notably, McCain denounced the administration’s lack of spine on Syria after Bashar Assad’s 2013 chemical attack on his own people. McCain calls Obama’s refusal to take strong action “the worst decision of his presidency … It shook the confidence of our allies and emboldened our adversaries, no one more so than Vladimir Putin.”

But mostly, McCain warned readers about the current president’s worldview. Denouncing the U.S.’s use of torture techniques in Iraq and Afghanistan — McCain himself was tortured in Vietnam — he noted that during the 2016 presidential campaign, “the eventual Republican nominee and next president of the United States insisted torture ‘absolutely works’ and swore he would bring back waterboarding ‘and worse.’”

McCain strongly denounced dictatorship and repression (“Putin is an evil man” and “China is the challenge of the century”) but mostly he was concerned with U.S. retrenchment from world affairs. He described himself as “not a Tea Party Republican. Not a Breitbart Republican. Not a talk radio or Fox News Republican. Not an isolationist, protectionist, immigrant-bashing, scapegoating, get-nothing- useful-done Republican.”

And so he decried the U.S.’s tendency to isolationism, and particularly its newfound willingness to blame migrants for its problems. “The great majority of unauthorized immigrants came here to find work and raise their families like most immigrants have throughout our history. They are not the rapists, killers and drug dealers of fevered imaginations on the right,” he says, adding that a “wall along the southern border isn’t going to solve the problem. It might make it worse.”

Of Trump, he adds, “His lack of empathy for refugees, innocent, persecuted, desperate men, women and children, is disturbing. The way he speaks about them is appalling… He hardly ever talks about human rights as an object of his policies. He went on a two-week, five-country trip to Asia, and never raised the subject.”

By contrast, McCain’s worldview seems straightforward. “When people peacefully appeal for their rights, we should encourage them. When they are thrown in prison, we should work for their release. When they face intimidation and violence, we should condemn it.”

Just as Canadians sometimes refer to Robert Stanfield as the “best prime minister Canada never had,” it seems natural to view McCain as the best president the Americans never had.

Other books of interest:

They Said No to Nixon: Republicans Who Stood Up to the President’s Abuses of Power

Michael Koncewicz

University of California Press, 2018

240 pages; $37.95

Apparently it can be done: Political appointees can push back when their leader — in this case, the president of the United States – abuses his position. Richard Nixon’s twisted personal plan was to use his position to punish his political foes, but people of integrity, some of whom he had appointed to their jobs, thwarted him by remaining loyal to their duties as public servants over their loyalties to their leader. Using material from the Nixon tapes and other fresher sources, the author explores the efforts of some within the president’s circle to safeguard the integrity of the Justice department, the IRS and other essential institutions of government.

Threshold: Emergency Responders on the U.S.-Mexico Border

Ieva Jusionyte

University of California Press, 2018

296 pages; $36.35

This book tells the story of the medics and other emergency workers who rush to take care of injured would-be migrants scrambling over the Arizona-Mexico border. These firefighters and paramedics operate at an intense human level while lawmakers clash over long-term politics and policies. Ieva Jusionyte, a trained emergency responder, puts real faces on issues ranging from migration and security to who gets public health care.

Carving Up the Globe: An Atlas of Diplomacy

Malise Ruthven, general editor

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018

256 pages; $52.74

Early diplomats (and modern ones, too) from powerful states like nothing better than to draw lines on maps and carve out nations and empires, it seems. This well-documented and lushly illustrated tome shows everything from the 1175 Treaty of Windsor to the 1713-14 Treaties of Utrecht to the Anzus Treaty of 1952. If diplomats have drawn it up, it’s in here, likely with a map and all the information you want to show you how things once looked — and to whose advantage borders were (and are) set.

Christina Spencer is the editorial pages editor of the Ottawa Citizen and the inaugural recipient of the Claude Ryan Award for Editorial Writing at the 2017 National Newspaper Awards. She holds a master’s in international affairs from the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University.