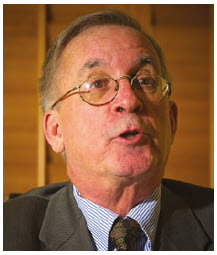

Scott Newark was a Crown prosecutor in Alberta until 1992. He also served as executive officer of the Canadian Police Association, director of operations to the Washington D.C.-based Investigative Project on Terrorism and as a security policy adviser to the governments of Ontario and Canada. He is currently an adjunct professor in the terrorism, risk and security studies program at Simon Fraser University. He sat down with Diplomat’s Jennifer Campbell to discuss terrorism, immigration and security — his areas of expertise.

Scott Newark was a Crown prosecutor in Alberta until 1992. He also served as executive officer of the Canadian Police Association, director of operations to the Washington D.C.-based Investigative Project on Terrorism and as a security policy adviser to the governments of Ontario and Canada. He is currently an adjunct professor in the terrorism, risk and security studies program at Simon Fraser University. He sat down with Diplomat’s Jennifer Campbell to discuss terrorism, immigration and security — his areas of expertise.

Diplomat Magazine: You’ve written about how Bill C-59 softened the terrorism propaganda offence section of C-51. You said that addressing the online publication of radicalization material is an important way to prevent domestic terrorism. What do we know about how propaganda plays into radicalization?

Scott Newark: It is a changing environment. One of the things we are aware of is that the bad guys aren’t saying ‘Come over here and help us fight.’ They’re saying ‘Take up arms in your own countries.’ That’s being done through the reality of social media. The ways in which you deal with the threat have to evolve to the nature of the threat as it evolves.

That was my real concern about Bill C-59 — the fact that it was taking something and reducing it. It was a fairly technical concern because the change in the legislation was to get rid of the generalized promoting or advocating evidentiary standard and to change it to counselling another person. I guarantee defence counsel will say, ‘Who is that person?’ and if you can’t prove who that person was, the offence isn’t there. Plus, it’s already a criminal offence to counsel someone to commit an offence. I don’t imagine [softening the legislation] was deliberate, but I think it’s a mistake. I testified at the committee and pointed that out and no one was able to address my concern about it.

DM: At the time of the Toronto van attack, you said authorities must continue to assess whether the attack was part of a bigger plan or would inspire copycats. How do they do that?

SN: Literally by checking the guys, using electronic devices. They have to get warrants to do all that, but they have the grounds to do it. They can interview them. When you’ve got a bit of evidence on something like this and there’s a suggestion that there may be something more involved, that’s what law enforcement has to do. The thing about copycats is that it’s a recognized trend. When something like this happens, it’s sometimes an inspiration for other people. This is why there’s an ongoing discussion about publicizing these things. The public has a right to know, but you don’t want to glorify it in such a way that it becomes inspirational to others.

Look at the work of Stewart Bell at Global News. He went to Northern Syria and interviewed the guys who have been detained. The Kurds have 13 Canadians detained, three of whom are male jihadis. There are three wives and seven kids. They all want to come back to Canada. The kids were born in Syria. The Kurds are asking the Canadian government to ‘Please come and take your people back.’ We haven’t done that. This one guy, who’s a sniper — Mohamad Ali — no one has talked to him. He wants to come back. Stewart put together a team and they went to Northern Syria and conducted interviews with this guy. My first comment: If Global News can do the interview, where the hell are the RCMP and CSIS and Global Affairs? There are specific things we can actually do. It’s that kind of analysis where you look at it and say ‘What are the options, where are the tools we need?’

DM: You’ve advocated for deploying vehicle access restrictions in specific identified mass-population venues — what other solutions would you suggest?

SN: It really is a model on things that are being done in Europe. The OPP, a couple of months ago, had a concern about an attack in downtown Toronto. It was reported then that the OPP has put in place a program so if people are renting vans, there’s a database the OPP can access. The [rental agency] can check with the OPP about whether the individuals renting are of concern. It’s also about taking lessons from past experience to try to find preventative measures and its security perimeters, mass-population venues.

DM: What are your views on the “caravan” approaching the U.S. from Latin America and what should be done?

SN: I think it is the manifestation or representation of what is probably the biggest challenge now facing Western countries, including Canada, in relation to the larger issue of how you deal with immigration and security issues. This isn’t something that happened to the same extent 20 years ago, so there has to be a development about how we’re actually going to deal with this.

I [like] the suggestion by Mexican President [Andrés Manuel López Obrador], that Canada, the U.S. and Mexico should come together to figure out some kind of strategy, so people don’t just try to illegally enter the U.S., Mexico or Canada. What’s really going on here is that you’ve got an organized effort for people to essentially simply ignore the laws of other countries. Countries have rules in relation to regular migration, asylum claims and everything else. This is an organized effort — the same way it’s happening from the Middle East and into the European Union. It’s saying ‘to hell with your laws, we’re going to come in and that’s just what you’re going to have to deal with.’ Coming up with a strategy to deal with that phenomenon is one of the great challenges.

I was involved in what led to the Safe Third Country Agreement. Back when I was at the Canadian Police Association — I think it was 1994 — a Toronto police officer named Todd Baylis was shot and killed by a career criminal named Clinton Gayle, who was supposed to be deported back to Jamaica. But the Jamaicans weren’t co-operating, so we were having difficulty removing him. Of course, he was released on bail and he went back to his chosen profession, which was being a drug dealer, and he shot and killed a young police officer. I was trying to find out what happened, but the walls of silence came up.

I asked for help [from the union that represents the frontline border officers] and they agreed for me to meet with the frontline immigration officers involved in the case and we learned the truth. It didn’t make any sense. The issue was why was he released on bail, given his record? [He was released because of procedural delays in getting the documents to remove him, which was largely due to non-co-operation from Jamaican officials.]

As I continued working with them on certain issues, I got alerted to the fact that at one point — towards the late ’90s — you know what country the largest number of refugee claimants to Canada came from?

DM: Which one?

SN: The United States. They weren’t Americans, but they were people transiting through the U.S. who decided they’d rather be a refugee in Canada because we have better health care and it’s easier to get welfare. Well, [that is not seeking protection], that’s called immigration — [instead they should] get in line with everyone else.

So we started discussions with the Americans. In late 1998, I worked with the Ontario government with the Office of the Victims of Crime. We were modernizing victim services, but I was also giving criminal justice policy advice because of my background. After 9/11 when the province of Ontario had a very strong relationship with the U.S. government, [we raised the issue with the Americans.] Bob Runciman was the [solicitor-general.] We started talking with the Americans and arguing that this makes sense.

They had instituted a program called NSEERS — National Security Exit-Entry Registration System — where essentially, they were creating a registry of everyone who was in the country on some kind of visa, and those from an Islamic country who’d overstayed. They were starting to crack down. They started with people from Iran and a whole bunch of them fled to Canada. I remember talking to the Americans and saying, ‘It’s not in your best interest to have them come to Canada because they can, at some point, go back to the United States. When we get them, collectively, we should deal with them, but we have to do that co-operatively. That is what led to the negotiations of the Safe Third Country Agreement.

After the Americans said they did want to move forward on this agreement, the federal government said it’s a federal responsibility and ‘We’ll do it.’ It was years later — maybe 2008 — when there was a huge surge in Mexican refugee claimants coming into Canada. [At that time,] someone from the minister’s office asked me about it and I said that shouldn’t happen under the Safe Third Country Agreement. I went and found the regulations under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and found the exceptions that are today causing problems. One was that it didn’t apply to people from non-visa countries. That’s why, when Jason Kenney was minister [of citizenship and immigration,] they put the visa requirement on Mexico. It was to stop that. The other one was nonsense that it doesn’t apply between ports of entry. To this day, [I don’t know] who came up with that idea, but that’s why we need to renegotiate with the Americans.

There was news recently that Customs Border Protection has just released data that the numbers of people entering the U.S. illegally from Canada is going up. [American border agents reported in October that 32,000 had entered in recent months. On the New Brunswick-Maine border, numbers were up to 54 apprehended in the first 10 months of 2018, versus 33 the year before.] If you think about it, if they’re cracking down from the U.S.-Mexico border, instead of paying a human smuggler to get you through, you get an airplane ticket to Canada, and now, thanks to Justin Trudeau, you don’t need a visa anymore. You land in Canada and then you just need to get across that border.

Looking at the bigger picture, you need to appreciate exactly what immigration includes. It includes screening so we know who it is who’s coming into the country. I’ve been involved for years on developing face-recognition biometrics. The point is you need to know who’s coming into your country. This may come as a surprise to some people, but sometimes, the bad guys use phoney ID.

After 9/11, I got an order-in-council appointment as the special security adviser on counter-terrorism. It was one of the issues that was very real after 9/11. We had people they actually called the yo-yo bandits. And it was significant because almost always in those cases, when you talk about people who’ve been deported for criminality, when we catch them is when they commit more crimes.

Quite apart from the public safety consequences, it’s also extremely expensive to investigate, prosecute, run a trial, incarcerate. So it’s costing us a huge amount of money. The reality is a disproportionately small number of criminals [is] responsible for a disproportionately large number of crimes. When you target those people, you get positive results.

When the Syrian refugees were brought in [in late 2015 and 2016, for example], they were going to bring them in and do screening afterward.

DM: On the security side, what are your chief concerns?

SN: There are multiple components to it, and you have a better chance of achieving the desired results when you have a fulsome understanding of what you’re dealing with. In terms of what security covers, probably the first area I dealt with was crime. If you’ve got more crime in your country, that affects public safety, which affects security. That’s one side of it.

The other side, which is still a reality, is espionage. I got involved in that in the mid-1990s, with respect to Chinese spying in Canada. David Kilgour, an ex-Alberta prosecutor, had crossed the floor as a Liberal by then and he had a [secretary of state position at Foreign Affairs.] What happened was that the foreign affairs people and an RCMP liaison in Hong Kong had done some really excellent work on the penetration into Canada of Chinese triads. As the work continued, it expanded into what Canadians ultimately called The Trinity — the organized crime groups, which were partnered with the Chinese government and the vehicle through which it was done was ‘business interests’ that were active in Canada. Many gained access to Canada through the Canadian immigrant investor program.

It was this brilliant intelligence officer from Foreign Affairs named Brian McAdam and RCMP Officer Garry Clement who exposed all of this stuff and were trying to get some answers when Brian was transferred back to Ottawa and basically stuck in the Xerox room. They destroyed him because it made them look bad. Ultimately, Kilgour asked me what was going on. It really is a deliberately complex web of activity. The RCMP and CSIS decided to do an analysis of it and produced a report called Sidewinder, which was a study of Chinese espionage, triad activity and influence on government. On the morning they were having the briefing [on the report], the order came from the Prime Minister’s Office [Jean Chrétien’s office] to shut it down and destroy all documents. The point is the activity hasn’t gone away. It’s part of a larger Chinese strategic interest and immigration is just one aspect of it.

There was a Chinese intelligence officer named Chen Young Ling who defected in Australia. He exposed everything and got tonnes of attention. Our Senate Committee on National Security, then chaired by Colin Kenny, had done a study that said, basically, that China was a very big security threat to Canada. It got some attention and this guy wanted to come and testify before the Senate committee. He came to Canada and we had lunch at David Kilgour’s place. I asked him: ‘How are you getting your people into the country?’ He described a number of scenarios — there’s the use of foreign skilled workers, [for example.]

This is an ongoing reality. Whether you see it in them acquiring assets or getting into security technology companies — it’s real. It’s not that all immigrants from China are security threats, but [immigration is] a tool that the bad guys use.

DM: What about terrorism — people who come to Western countries to commit terrorist acts?

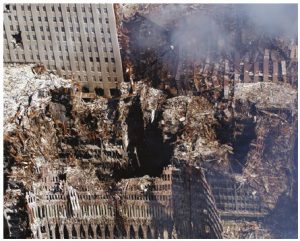

SN: The best example of that is 9/11. I remember relatively immediately afterwards, as we learned the profiles of these guys and we realized they’d used the U.S. immigration system to [commit their acts]. I was relatively confident we could take measures to work against that. My concern was with the people who are already here.

DM: What does one do about them?

SN: You start to pay attention and you look for the groups with Muslim Brotherhood links. This is work I did down in Washington with the investigative project on terrorism. It’s not necessarily tied to immigration, but to go back to my point from before, when you find organizations that are trying to block integration, that’s a red flag. The Canada Revenue Agency has just shut down funding and charitable status on a number of Muslim Brotherhood and related groups.

DM: We’ve touched on it, but what can governments do about mass migration?

SN: We need to come up with a strategy that creates an incentive to people to obey our laws. That’s why the Mexican president’s idea of a camp where people can apply for refugee status is the way to go. They’re trying to avoid the screening when they organize the caravans.

The most recent data show that more than 50 per cent are people who are coming from other countries, lawfully getting a visa to go to the U.S. and then they’re sneaking into Canada. Why? Why not get a visa and come here and claim refugee status at an airport? It’s because they don’t want to go through Canadian screening. We do a better job on screening than the Americans.

One of the biggest problems we have, unfortunately, is a shortage in personnel at [Canada Border Services Agency]. In 2013, the Harper government came up with the deficit-reduction action plan. It was supposed to cut bureaucracy and back-office paperwork. But the leadership at the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) allowed it to cut frontline officers who do primary and secondary inspections. As a result, [this] has cut our capabilities, which is really serious. If the government wanted to pick a single thing to improve border security, it would be to put those resources back into CBSA.

The other thing that makes the point on mass migration: I remember watching an interview with Moammar Gadhafi. This notion of Islamic terrorism was in the news. They were asking about all these people who were flooding into Europe. I remember him laughing and saying ‘Yes, you’re all worried about invasion and bombing. What’s actually going to happen is immigration and birth rates. That’s how we’re going to take over.’

The status quo is not going to be a solution because this isn’t going away. People need to candidly acknowledge that and look for solutions rather than yelling or doing nothing.

In the context of immigration and security, another challenge is [not to forget] that just because of the geopolitical circumstances, we have to make sure we have that bad-guy lookout system. It should be on foreign criminals. You don’t want every person in the world, but [you want] high-risk kinds of offenders. There have been discussions of it over the years. We need to make sure we work with each other so we have information and we’re using the right technologies.

DM: What kind of technologies?

SN: I don’t know whether it’s been put into place yet. It’s called the Advanced Passenger Information System that CBSA is finally implementing. It used to be, believe it or not, that if you were flying to Canada, you got on the plane and once the plane was in the air, [the airline] sent the information to CBSA, as opposed to doing it before the plane took off. We’ve done what we can on our side. I gather there’s been some dragging on the European side as to whether they’ll share this info. The technology isn’t complicated — as you’re standing at the counter, your picture is taken. You have to do it in a fair way. It isn’t [happening] at this point, but it could be and should be, with a legal requirement that the data must be destroyed within 24 hours.

DM: Do you see any members of the caravan eventually arriving in Canada?

SN: Wouldn’t surprise me, which is why I think the Mexican president is correct in saying we should put together a facility where they’re all secure and can make their claims.

If you do get caught trying to enter the country illegally, instead of catch and release, it should be catch and return to their home country. That’s logically the best way to proceed.

DM: In a piece called “Cutting cheques is not the answer,” relating to Canada settling lawsuits with Omar Khadr and Mahar Arar, among others, you called for express statutory authorization for defined interactions and information sharing by certain Canadian officials on terrorism cases with international entities. Has there been any progress on this?

SN: No. A big part of why it was determined Canada had violated the Charter of Rights [for folks such as Mahar Arar] was either because our people didn’t do anything or did do something. I got to know Omar Khadr’s U.S. Navy lawyer very well. I told him his client was on TV making a roadside bomb and [to] ‘cut the best deal you can and ask for transference.’ It was the Harper government that sent the letter to the American authorities saying Canada would give ‘favourable consideration’ to a request for transfer under the International Transfer of Offenders Act. The point, though, is if there’s no statutory authorization that raises the potential of it being a Charter breach. If there’s a statute authorizing an official to do something, then you can say ‘this isn’t just us acting on our discretion, we have specific authority to do this.’

All we’ve ended up doing on these cases is throwing our officials under the bus and creating a risk-averse culture.

DM: You commented on Bill Blair’s appointment as minister of border security and organized crime reduction. In your estimation, how has he been doing since his July appointment?

SN: I haven’t seen any specific results or actions taken. They’re been very focused on the marijuana legalization, in fairness. As I know Bill, he is someone who’s capable of getting things done.

DM: Specifically, how is he doing on irregular migration, especially in Manitoba and Quebec?

SN: My sense is that he recognizes there needs to be engagement with the Americans — to say we need to modernize the Safe Third Country Agreement. There are actions that can be taken. For example, gun smuggling: If you have guns and you come between ports of entry. It may be a federal act, but it has local impact. Because of his background, he understands that. I can see him taking action on that and also on modernizing CBSA to give them authority between ports of entry. I’m cautiously optimistic that he’ll be someone who will want to see results as opposed to someone talking in blather.

Some things are complicated, but putting more money into border security’s frontline operations [would be advisable]. [According to a Global News item from October the numbers are up this year. By September 2017, there were 15,102 RCMP interceptions of irregular border crossers and as of September 2018, there were 15,726.]

DM: Should Jihadi Jack be allowed to return to Canada?

SN: I’ve never really studied that particular issue, but my understanding is that he does have Canadian citizenship. I believe in the rule of law. And if the law is that as a Canadian, he is entitled to come back to Canada, I don’t think we should look the other way.

DM: How do you feel about a person born in a country to parents who are not citizens automatically becoming a citizen?

SN: Anchor babies, we used to call them. I can see the logic philosophically, of why you grant citizenship, but once again, there’s a reason they call them anchor babies. It’s what the Khadr family did. They wanted to make sure their kids were always born in Canada. I guess my instinct would be to look at how I prevent that from happening in the first place. We knew what the Khadrs were doing. I think the biggest lesson out of the Khadr case is why child welfare services never took those kids away.

Let’s say we do get off our asses and bring these people back that the Kurds have. You have three wives and a bunch of kids. It is entirely appropriate to ask whether the conduct of the wives constitutes a terrorist offence. If it doesn’t, you could ask whether their activity would be placed under a peace bond. I think you could make a pretty compelling case about that. But the first thing I’d do is to have the child welfare people take a look and make sure those kids aren’t at risk by having their parents around. The Khadr kids deserved better. We failed them.

DM: Does it encourage demand for giving birth in a foreign country as a direct path to citizenship versus applying from a foreign country first?

SN: Yes. I’m not kidding about the name — they’re actually known as anchor babies. It’s the same reason [asylum-seekers try to avoid] processing. The longer the system takes to make a decision, the greater the chance the person has to say ‘I may be inadmissible, but I’ve been here for six years, so please grant me admission on humanitarian grounds.’ People understand and are going to play the system, which is why we should have expedited decision-making processes on different kinds of cases.