Humans have discussed the origin and outcomes of income inequality for millenniums. The sacred texts of all major monotheistic religions generally denounce it, but contemporary interpretations of the same faiths often disagree about the best way to remedy it, or if a remedy is even necessary.

Aristotle considered it corrosive for political communities; European medieval societies institutionalized it through feudalism. Jean-Jacques Rousseau warned of its corrupting influence on the psychological health of individuals in the 18th Century and Karl Marx argued in the 19th Century that it would lead to the fall of capitalism after being responsible for its historic rise.

Such central economic thinkers of the 20th Century as Harvard University professor Joseph Schumpeter downplayed its significance, as long as society ensured social mobility. And Austrian-born British economist Friedrich Hayek considered it fundamental to progress.

U.S. academic John Rawls, perhaps the most important political philosopher of the 20th Century, considered it unjust if it does not benefit the least well-off, while his American contemporary, Robert Nozick, warned against measures that forbid “capitalistic acts between consenting adults.”

Civil rights leaders, feminists, environmentalists and non-Western philosophers of various ideological hues have since expanded this discussion, starting with the 1950s and stretching into the present, by linking income inequality to racial injustice, male domination, the unsustainable exploitation of the natural environment and northern control of the globe’s southern hemisphere.

Others have dismissed these critiques, and it was not so long ago that Simon Kuznets, Nobel laureate in economics, argued that inequality would eventually disappear “because growth is a rising tide that lifts all boats.”

Former U.S. president Barack Obama has declared income inequality “the defining challenge of our time” and various commentators have argued that the rise of economic populists around the world reflects a desire to reform the worst defects of capitalism in the early 21st Century, including its growing income inequality.

In short, perspectives on inequality have varied over time. As French economist Thomas Piketty writes in his ground-breaking book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the “history of the distribution of wealth has always been deeply political, and it cannot be reduced to purely economic matters.”

He also states that the “history of inequality is shaped by the way economic, social and political actors view what is just and what is not, as well as by the relative power of those actors and the collective choices that they make.”

These choices actually start with the methods that researchers choose — or don’t choose — in presenting the very phenomenon they seek to describe.

As Piketty and his co-authors in the 2018 World Inequality Report acknowledge, these choices are not neutral and may substantially impact not only findings, but also policies.

We have chosen the Gini index to present the 10 countries with the greatest income inequality. As with all inequality measures, it is the distribution that shows the number of individuals in any group and their share of the group’s total income or wealth.

Drawing on the work of American economist Max Otto Lorenz, the index developed by Italian economist Corrado Gini represents the average distance between the income or wealth between all individuals, if paired up.

If the Gini index is zero, everyone has the same income. If the index is 100, one person possesses all the wealth. So what does this list show? Overall, it identifies Africa — especially sub-Saharan Africa — as an epicentre of inequality, along with Latin America. More fundamentally though, it underscores the importance of institutions, which themselves reflect political choices.

Most of the entries on this list possess enormous economic potential, which, if realized, could be more equally shared. Yet these elites have chosen the selfish path of personal enrichment at the public’s expense by rigging institutions in their favour and by undermining the rule of law with pluralistic politics and lack of transparency by way of the media and non-government organizations. Such moves may pay off in the short term for the few who practise them, but their persistence will eventually bring misery upon all. As such, this list is not just a snapshot of the present, but also a warning about the future.

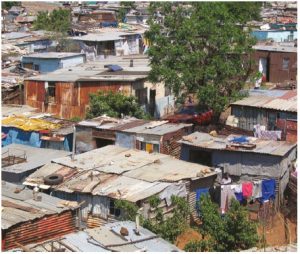

1. South Africa:

The world’s most unequal state is also the most industrialized state of the African continent. The sole African member of the G20, which represents 19 industrialized and emerging countries plus the European Union, recorded Gini index of 63 in 2015, the highest in the world, as reported by the World Bank’s March 2018 South Africa Poverty and Inequality Report.

Worse, inequality has been rising since the end of apartheid in 1994. South Africa’s Gini index stood at 61 in 1996 and actually peaked at 65 in 2006 before “dropping” to its current rate, which would have been 10.5 points higher without social assistance.

Other measures confirm South Africa’s high degree of inequality. It ranks last among surveyed states on the Palma Index (the ratio of the richest 10 per cent of the population’s share of gross national income divided by the share of the poorest 40 per cent) with a ratio well above 7, according to multiple sources. Wealth inequality even exceeds income inequality.

Reasons for this state begin, but hardly end, with apartheid’s legacy. “South Africa inherited very high inequality from the time of apartheid, and it increased since,” the World Bank states in the same report.

Inequality has increased because the polarization of the South African labour market has intensified. As the World Bank says, South Africa possesses two economies: a productive one that allows a small number of skilled people to access highly paid jobs; and an unproductive economy that employs a large number of unskilled individuals with low wages.

Worse, a lack of social mobility and sluggish job growth have closed off the first labour segment from the second, trapping individuals in poverty across generations.

True, poverty rates have dropped since apartheid, as South Africa has emerged as a genuine global player as a member of the BRICS group. But the unequal distribution of these dividends bedevils South Africa. “Race,” writes the World Bank, “still affects the ability to find a job, as well as wages received once employed.” Gender does, too.

But other factors, such as access to education, increasingly determine social outcomes in South Africa, and South African elites starting with the ruling African National Congress (ANC) will find it increasingly difficult to blame others for current deficits a quarter century after South Africa began its long journey into freedom.

2. Namibia

A long list of issues faces this former German colony, which did not shed South African control until 1990, following occupation during the First World War. The list includes the effects of HIV/AIDS (12.1 per cent of its adult population lives with it), and climate change that threatens its large agricultural sector and bio-diversity, a major source of foreign income through tourism. Not surprisingly, the list also includes inequality, with a Gini index of 61.

Foreign interference, coupled with periods of civil war, had destabilized Namibia for decades before independence and left behind a legacy of race-based apartheid at least partially to blame for its high inequality, according to a World Bank report titled Does Namibia’s Fiscal Policy Benefit the Poor and Reduce Inequality? While poverty rates have “declined substantially” since the early 1990s from 58.9 per cent of individuals in 1993-1994 to 15.3 per cent in 2009-2010, according to the report, “daunting challenges” remain.

Namibia should be rich, thanks to its wealth in precious gems and minerals, including uranium, of which it is one of the world’s largest producers. Yet only a minority of the population lives in conditions expected in an upper middle-income country. The World Bank notes that “a century of colonial rule and apartheid concentrated Namibia’s wealth — including ownership of land, companies and financial assets — in the hands of a small minority,” according to the World Bank.

Consider the following: In 2009-2010, the richest 10 per cent of Namibia’s population accounted for 70 per cent of personal income taxes because of low labour-force participation.

Namibia (like its southern neighbour and former colonial master, South Africa) confronts a “triple challenge” of poverty, unemployment and inequality. While the economy has steadily grown over the years, it has not grown strong enough to create a sufficient number of jobs that would lift its population out of poverty, thereby reducing inequality.

But if Namibia (along with South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland) confirms southern Africa as perhaps the most unequal region of the world, it is also a role model for them.

Oxfam, for example, recognized Namibia in the second edition of its Commitment to Reduce Inequality Index (CRI), and none other than U.S. economics Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz (along with co-author Anya Schiffrin) praised Namibia’s exemplary efforts to reduce inequality through various measures that focus on unleashing human potential starting with, but not ending with, education. They include efforts to improve medical services and infrastructure, while rooting out corruption by way of guaranteeing press freedom.

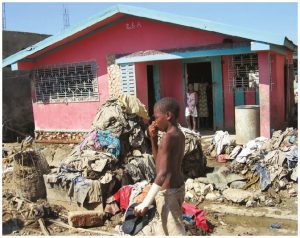

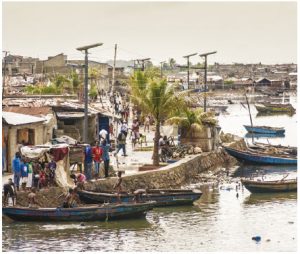

3. Haiti

Jovenel Moïse entered Haitian politics as an unknown figure who made familiar promises: Improve the economy, especially agriculture; rebuild infrastructure; and curb corruption. Bearing the nickname of Banana Man because of his background in produce, Moïse emphasized his entrepreneurial credentials as evidence of his political effectiveness. Fewer than two years after assuming office in February 2017, Moïse’s record is poor.

The economy remains stuck and an unpopular hike in fuel prices, part and parcel of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund, led to deadly riots in July 2018 that included demands for his political departure. Moïse, unlike then-Haitian prime minister Jack Guy Lafonte, has remained in office, but his grip on power appears tenuous, as his government continues to confront public anger over pervasive corruption — in this case, allegations that a Venezuelan-led oil alliance funnelled funds into the pockets of public officials. Moïse, in promising justice, has fired individuals connected to the PetroCaribe scandal. Haitians, however, have heard such claims before, and few are likely to believe them.

This unfolding episode encapsulates one of the reasons, if not the central one, behind Haiti’s pervasive inequality: The cast of political characters rotates, but corrupt institutions persist.

As American sociologist Scott G. McNall argues, it is this corruption that has kept Haiti poor, for it serves as an “almost perfect example” of what MIT economist Daron Acemoglu and Harvard economist James A. Robinson describe as a society with closed political and economic systems. Writing in Why Nations Fail, they state “extractive political institutions in the hands of a narrow elite place few constraints on the exercise of power. Economic institutions are then often structured by this elite to extract resources from the rest of the society.”

Wealth, accordingly, concentrates in the hands of the few, leaving the many with little— and little faith in their institutions.

A 2009 survey found more than 50 per cent of Haitians bribed officials to secure services, and fewer than 15 per cent asked their own government for help after the 2010 earthquake that destroyed large parts of the country.

Perhaps worse, the concentration of wealth at the very top of Haitian society — Haiti records a Gini index of 60.8 — only deepens corruption as groups try to preserve their sinecures. It also encourages political instability as elites compete against each other for them, creating a vicious cycle that deepens violence and corruption, while inequality persists.

4. Botswana

This former English protectorate might be land-locked, but it is nonetheless an island of bliss amidst the many storms that swirl through sub-Saharan Africa.

First, its government has proven stable and its institutions strong. While military coups remain routine across the region, Botswana can look back upon more than five decades of uninterrupted civilian government. However, the ruling

Botswana Democratic Party has won every election since independence in 1966 and Freedom House, a watchdog organization, has raised concerns about its increasingly authoritarian ambitions, as it has stifled the media, sought to pack the courts and discriminated against various ethnic and sexual minorities.

But Botswana’s multi-party system allows political opponents of President Mokgweetsi Masisi to organize themselves, and outside observers consider local elections to be free and fair. Second, Botswana’s government has pursued a number of economic policies that have expanded opportunities for its population, now numbering around two million. These policies include, among other measures, reducing fertility, while raising the educational achievements of women. (Economists and other experts fear that Africa’s baby boom represents a major source of political poverty and instability in light of sluggish growth).

Third, Botswana’s elites have avoided the resource curse that has crippled so many other African nations. Elites could have easily captured the mineral wealth of the country, as Botswana is the world’s second-biggest producer of diamonds. But the presence of an independent judiciary and various anti-corruption measures have deterred the kind of corruption that has devastated other countries. (It ranks 34 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Index; and it’s the least corrupt of African nations).

Not surprisingly, the international business community likes this sort of stability.

Fitch Solutions — which assigns Fitch Ratings — touts it in its assessment of Botswana: “Botswana is likely to continue enjoying broad-based political stability over the next years.”

But this assessment also includes a cautious note that specifically highlights Botswana’s “highly skewed” income inequality with a Gini index of 60.5. To be clear, Fitch’s assessment of Botswana is largely positive. But it identifies income inequality as a “high-impact risk” that could lead to “increased instability in the next decade.” This said, Fitch considers the probability of such an outcome “low.” Still, this assessment neatly highlights the corrosive potential of inequality.

5. Central African Republic

Lost among the litany of human sufferings coming from corners of the world such as Syria, Yemen and South Sudan lies the Central African Republic, whose Gini index of 56.2 arguably ranks among the least of its problems.

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof has called this landlocked country of 5.6 million the site of the world’s “most neglected crisis” thanks to more than 14 years of civil war and ethnic cleansing with a changing cast of armed groups. It’s been six years since the start of the most recent conflict that pits militia from CAR’s Christian majority against rebels from its Muslim minority and half of the population now needs humanitarian assistance.

More than a million people — roughly a quarter of the population — find themselves on the run either inside or outside their own country. This crisis has received just as much attention from the global media as it has from international donors and organizations — namely, next to none. Crises in the Middle East, not to mention neighbouring Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, have overshadowed events in CAR, and little, if any, international aid has reached the country, despite an overwhelming and growing need. The security situation has forced humanitarian organizations to head home, and a high-ranking UN official had spoken in 2017 of a genocide in the making as tensions between rivalling factions remain high, despite the presence of UN peacekeepers and mediation efforts.

In fact, it is hard to find a corner of the country where groups of various sorts are not competing against each other. Many of these ethnic-religious conflicts have economic origins, a familiar phenomenon for many resource-rich countries. CAR’s catalogue of natural resources includes oil, gold and diamonds and its rich soil grows such cash crops as cotton, coffee and sugar, as well as food crops such as corn, yams and millet.

Yet decades of mismanagement and civil unrest following decolonization have denied CAR fulfilment of its potential and left it with a legacy of inequality that only hints at larger problems.

Government in the Central African Republic is not just corrupt, it is largely absent — or as Kristof writes, “mostly just a rumour.” CAR — along with some of its immediate neighbours — brings to mind philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ state of nature, where “every man is enemy to every man,” thanks to the absence of authority, an absence that leaves behind “no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain” and “which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death, and life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

6. Zambia

This landlocked sub-Saharan African country of 15 million people currently finds itself in the spotlight because of its escalating debt caused by allegedly unsustainable loans from China. China holds somewhere between a quarter and a third of the country’s debt, which has increased rapidly, from 21 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2011 to 59 per cent at the end of 2017, according to The Economist. Western observers, including senior U.S. officials, have warned that Zambia represents an example par excellence of the “debt-trap diplomacy” that China pursues in Africa and Asia as part of its hegemonic Belt and Road Initiative.

Non-Western voices have acknowledged this argument, but also added that Western countries have contributed to this problem, too. Regardless of the reasons, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has identified Zambia as one of 18 African countries at risk of debt distress, with another eight already in debt distress, meaning that they are delinquent or in default. Zambia’s debt level does not only make it politically dependent on others, it also poisons the well for business, and worse, undermines any efforts to deal with the country’s inequality (its Gini index is 55.6.) The biggest budget item in Zambia, as The Economist notes, used to be education. “Today,” it says, “it is debt service, with nearly a quarter of government spending going to pay back loans.”

Back in 2005, the IMF cancelled all of Zambia’s debt (upwards of $6.6 billion US). That grace and a high price for copper, Zambia’s main export, helped spark an average annual growth of seven per cent between 2000 and 2010. Zambia, in other words, had a chance to ease inequality. But a toxic combination of easy money and widespread corruption helped Zambia’s kleptocratic and increasingly authoritarian elite squander the IMF gift and this chance.

7. Lesotho

Its status as a constitutional monarchy and stunning mountains have earned this enclave the popular nickname of the Kingdom in the Sky. More than two thirds of its 30,335 square kilometres is mountainous, with many areas only accessible by horseback or light aircraft. For foreign photographers and adventurers, Lesotho offers unique sights, including snow-covered mountains, a rare sight in Africa by any measure. The reality for the 2.2 million residents of Lesotho is a different one, with the harsh mountainous nature of their realm rendering their livelihoods very difficult.

They use 76.1 per cent of their land for agriculture, but only 10.1 per cent of this is arable and areas with permanent crops account for 0.1 per cent of total agricultural land. The rest — 65.9 per cent — is suitable for animal herding.

Its exports consist of two commodities — water and people — with both flowing towards South Africa, its only neighbour. Those who remain, in turn, scratch a living out of the land, while relying on remittances from those who toil in the mines and homes of South Africa, as miners or domestics.

Remittances, according to the CIA’s World Factbook, account for 17 per cent of the country’s GDP. A small textile industry dominated by immigrants from Taiwan and mainland China has started to emerge. But Lesotho ranks as one of the poorest countries in the world with a per-capita GDP of $3,600 US in 2017, ranking it 186th globally, according to the World Bank. This is one reason its index is 54.2.

Poverty is not the only reason. Other key reasons include corruption and civil conflict as its elites find themselves in a constant struggle to control the country’s few spoils, as evidenced by the recent run of political instability.

8. Colombia

This Latin America country of 48 million finds itself near the top of many regional and global economic rankings. It is the fourth-largest oil producer in Latin America, the world’s fourth-largest coal producer and the world’s third-largest coffee exporter. In short, it possesses natural wealth. But this natural wealth has not reduced — at least not yet — income inequality in Colombia, whose Gini index of 53.5 makes it the most unequal country in a region defined by inequality.

True, Colombia has managed to reduce poverty during a period of growth, fuelled by oil, that stretched from 2006 to 2014. This is no small feat in light of the fact that Colombians have found themselves in the middle of a civil war that started in the mid-1960s and did not officially end until late November 2016.

A 2015 World Bank report argued that per capita income in Colombia would have been 50 per cent higher if it had been at peace for the past 20 years. Yet the peace dividends promised by the 2016 settlement between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) have not yet materialized, partly because the other major left-wing rebel group — the National Liberation Army (ELN) — remains outside the peace process and continues to harass Colombia’s oil industry. Colombia also remains the world’s largest producer of cocaine, and the right-wing government of newly elected Ivan Duque has promised to step up enforcement against the country’s powerful drug cartels, a move likely to raise the level of political violence. Finally, Colombia has failed to redress its unequal distribution of land, one of the systemic reasons for its political instability and, therefore, inequality. An Oxfam analysis shows that the largest one per cent of landholdings concentrate 81 per cent of available land, forcing the remaining 99 per cent of farms to share 19 per cent of the remaining land.

9. Paraguay

The history of this landlocked South American country of seven million people point to many of the same conditions and circumstances among countries of great inequality. First, Paraguay has deficient infrastructure, though the country’s economy would do even worse without its natural waterways. Second, corruption is endemic. As Transparency International noted in a briefing on Paraguay, the 35-year-long military regime of Alfredo Stroessner had two defining features: its gross violation of human rights (which the West quietly tolerated) and the institutionalization of corruption. “Corruption is the price for peace,” Stroessner himself said.

While Stroessner’s regime ended in 1989 following a military coup that eventually restored electoral politics, corruption has survived and thrived, touching every area of Paraguayan society and daily life.

The 2013 Global Corruption Barometer, for example, found at least 36 per cent of respondents said they had paid a bribe and 61 per cent said they thought corruption was getting worse — not better.

To be fair, Paraguay has made efforts to fight corruption in order to attract more international investment (especially in the area of infrastructure). In this context, Taiwan has emerged as an unlikely partner through a shared history of strident anti-communism.

Whether additional growth will help reduce Paraguay’s Gini index of 51.7 is another question, in light of corruption.

Finally, the distribution of resources is highly unequal, especially in the important agricultural sector, which accounts for almost 18 per cent of its GDP. Paraguay is one of the world’s most important producers of soybeans.

According to Transparency International, only one per cent of the population owns 77 per cent of arable land and the poverty rate in rural areas hovers around 45 per cent — more than 20 points higher than in the urban areas.

10. Brazil / Eswatini (formerly Swaziland)

On the surface, these two countries could not be more different. One is Latin America’s largest country by area (8.51 million square kilometres) and population (almost 210 million) and is an emerging global power whose influence resonates far beyond its southern hemispheric borders. The other is a landlocked spot in Africa, roughly three times the size of Prince Edward Island with an estimated population of fewer than 1.5 million people.

One has one of the world’s largest economies with a 2017 GDP estimated at $3.24 trillion, ranking it ninth globally, according to the CIA World Factbook. The other has a total GDP of $11.34 billion, putting it in 159th place. And yet these two countries share the same Gini index of 51.5. Of course, it would be a mistake to make too much of this statistical match.

Both places took very different paths towards their respective states of inequality and they possess different resources to escape them. Major demographic and immutable geographic differences quickly render any comparisons mute. Still, these two countries share more than just the same Gini index. First, large sections of their respective societies are not active participants in the economy, leaving them in poverty.

Second, both countries are dealing with the effects of infectious diseases (including HIV/AIDS) that strain public resources, create private poverty and undermine human capacities. Third, both confront a host of environmental issues that threaten their long-term economic future, especially in Eswatini, where climate change threatens subsistence farming. Fourth, both countries have suffered and continue to suffer from corruption that misdirects resources and undermines the legitimacy of institutions. (Notably, both countries find themselves near each other in the rankings of International Transparency, with Eswatini scoring 39 out of 100, Brazil 37 out of 100).

In fact, corruption was perhaps the defining issue during Brazil’s divisive 2018 presidential elections in the aftermath of a money laundering scandal, with the eventual winner, Jair Bolsonaro, promising to drain the swamp. Whether his efforts are sincere and effective is uncertain.

Five most equal

Ukraine: 24.1

Unlike its big neighbour, Russia, with its own Gini index number of 41.6, Ukraine has avoided excessive inequality. Reasons include, among others, measures that curb corruption (though more measures are needed). But unlike its large neighbour, Ukraine’s per capita GDP of $8,700 US is lower than Russia’s $27,800. Ukraine’s challenge, accordingly, lies in raising growth while maintaining its commitment towards equality, a difficult balancing act in light of its fraught relations with Russia over the latter’s annexation of Crimea and ongoing incursion in Ukraine’s eastern region of Donbass.

Slovenia: 25.6

Melania Trump, wife of the current U.S. president, has undeniably raised the profile of this country, which emerged out of the former Yugoslavia in 1991. Perhaps less well known, however, is its reputation as the little economic engine that could, thanks to a well-educated workforce, excellent infrastructure and stable democratic system. As a member of the European Union, the European customs union, the Schengen area and the Euro currency zone, Slovenia has sought to take full advantage of European integration, not to mention its strategic location between the Balkan countries and Western Europe. Accordingly, it leads all successor states of the former Yugoslavia in terms of per capita GDP with $34,400 US (2017), while remaining mindful of inequality.

Norway: 25.9

Liberal circles of the North American commentariat have long praised the inequality-busting policies of Scandinavian countries such as Norway, where successive governments have used wealth from oil discovered in the 1960s to build up human capacities through investments in education and other policies. With a per capita GDP of $71,800 (2017), Norway is ahead of all G7 economies (including Canada and the U.S.) while maintaining one of the lowest levels of inequality. True, oil always helps. But the respective Gini indices of Finland (27.1), Sweden (27.3) and Denmark (29.1) — Scandinavian countries without oil — suggest that the Scandinavian model relies on more than just mere riches to produce one of the wealthiest and happiest corners of the globe.

Slovak Republic and Czech Republic: 26.1

2019 marks the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution during which the former Czechoslovakia peacefully freed itself from Communist rule and Soviet tutelage. Fewer than four years later, the country went peacefully through the Velvet Divorce as it separated into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. More than a quarter-century later, many ties continue to bind the two successor states, including a “history of shared institutions and similar transformations” that “can be expected to manifest [themselves] in similar inequalities with similar development,” as a 2014 scholarly article on the two countries noted. (The article notes that taxation and transfers have “significantly” mitigated income equalities). But scholars are also expecting growing inequality in both countries in coming years. If health care and education “largely” determine the future prospects of inequality, trends are diverging. While the Czech Republic is spending more on health care, Slovakian spending is stagnating.

Academics also find that the Czech and the Slovak education systems remain “notoriously underfunded and in need of structural reforms, yet there have been few signs of improvements.” Finally, respective Roma minorities of both countries continue to find themselves on the margins.

Wolfgang Depner holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia and writes in Victoria, B.C., where he teaches philosophy and Canadian history at Royal Roads University. He has also taught political philosophy and international politics at the University of British Columbia (Okanagan).