Bruce and Vicki Heyman’s The Art of Diplomacy (Simon and Schuster, 2019, 266 pages, $32) is a syrupy fan letter to Canada — a collection of clichés about our weather, our pronunciation, Tim Hortons and Sourtoe cocktails. About the only thing missing is an ode to the BeaverTail.

Still, Canada these days needs to welcome love where it can find it, and praise from Americans isn’t something we often hear. Usually they don’t notice us. The Heymans hope to change that.

The book, by the former U.S. ambassador to Canada and his wife, is also a fan letter to Justin Trudeau, filled with breezy bromides about his stellar leadership. One can imagine that the prime minister, after a disastrous start to Election Year 2019, is also happy to accept the praise.

And the Heymans, though they come across a bit like annoying high school cheerleaders, seem sincere and likeable. They’re a down-to-earth couple who clearly enjoyed their almost-three-year tenure as “co-ambassadors” to Canada on behalf of Barack Obama’s administration.

Wait, correction — you can’t have co-ambassadors. The couple is told this when the position is initially offered by a U.S. administration official who asks which of them wants the job. “You do know you are both qualified,” he tells the former Obama fundraiser-philanthropists. Ultimately, the Heymans decide Bruce will be the official envoy, but his outgoing, personable wife will play a key public role.

And she does. Bruce Heyman deals in conventional ambassadorial diplomacy; Vicki forges relationships in the world of art and culture. The Heymans alternate as authors of various chapters, reflecting slightly different experiences, but always the same upbeat message about Canadians. Who knew we were this great?

Still, for a book written by a heavyweight diplomatic couple, there is surprisingly little substantial diplomacy discussed. Obviously state secrets and delicate negotiations can’t be revealed, but the relentless omission of almost any weighty policy content tends to reinforce the stereotype that what ambassadors do is host parties, travel and hob-knob with cool people. [Examples of issues at the time include the anti-nuclear agreement with Iran, labelling of Canadian beef, president Barack Obama’s early-announced troop pullout from Iraq, Canada’s presence on the U.S. watchlist of countries not fully implementing treaty commitments enforcing internet and copyright piracy and the refusal by the Obama administration to share the construction cost of the new Gordie Howe International Bridge Windsor-Detroit Bridge.]

The exception is the heated debate around the Keystone XL Pipeline between the Stephen Harper government and the Obama administration during the first part of the Heymans’ tenure in Ottawa. Bruce recounts how, from the start, he is pressed by Canadian leaders to convey to Obama how fervently Canada wants the pipeline segment in Nebraska approved. Early on, he is called in to the Department of Foreign Affairs to be (politely) dressed down over Keystone by then-deputy minister Daniel Jean. “In the days that followed, I noticed that all meetings I had scheduled with various ministers, for one reason or another, were cancelled,” he writes. “Message received: I was shut out.”

Ever optimistic, the Heymans use their political isolation from official Ottawa to travel the country — seven provinces in 21 days on their first foray — and they love us all instantly. They also learn. Meeting with elders of Great Bear Lake, they hear powerful pleas for wise stewardship of the land. “In the United States, Bruce and I have limited contact with Native Americans,” writes Vicki. “But in Canada we developed over time a huge network of Indigenous acquaintances and friends … I had to wonder, if Canada was able to recognize its past abuses of Indigenous people, why couldn’t the United States do the same?”

Ever optimistic, the Heymans use their political isolation from official Ottawa to travel the country — seven provinces in 21 days on their first foray — and they love us all instantly. They also learn. Meeting with elders of Great Bear Lake, they hear powerful pleas for wise stewardship of the land. “In the United States, Bruce and I have limited contact with Native Americans,” writes Vicki. “But in Canada we developed over time a huge network of Indigenous acquaintances and friends … I had to wonder, if Canada was able to recognize its past abuses of Indigenous people, why couldn’t the United States do the same?”

Another impact of the Harper freeze-out is the Heymans’ evolving friendship with the third-party leader of the day, Justin Trudeau, and his family. Vicki becomes chummy with Sophie Grégoire-Trudeau (the two even take off for lunch on Sophie’s Vespa, to the alarm of embassy staff). At a dinner together at Lornado, the official residence of the U.S. ambassador, the Heymans and the Trudeaus bond.

“What was clear to me even then was that (Trudeau) was a man of conviction; someone who was authentic, honest and had a clear perspective of what he wanted for Canada — and what he didn’t,” Bruce Heyman writes of that evening meal.

The book is replete with such gushing about the Liberal leader (there is no reason to think it’s insincere: They like him, they really like him). But what’s odd is that while the Heymans eagerly describe the early frost in their relations with Harper — more on that in a minute — and the warmth of their friendship with Trudeau, the book never mentions the then-leader of the Official Opposition, the NDP’s Tom Mulcair. For much of the Heymans’ tenure, the NDP was running strong in the polls and Mulcair might well have knocked out Harper as prime minister. In the Heymans’ book, however, he doesn’t exist.

But back to Harper. Bruce Heyman writes that relations finally thawed when he rescued the prime minister from a foreign policy gaffe. In September 2014, Heyman writes, Harper told the media that the U.S. had asked Canada to join the bombing campaign in Iraq. Apparently no such invitation had been issued, and reporters were asking awkward questions. “It was obvious to me that Prime Minister Harper and his team were in a bit of a jam,” Heyman notes. So the ambassador stepped in with this statement: “On behalf of the U.S. government, I’d like to formally invite Canada to participate in the Iraq effort … any and all help from Canada in the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS would be deeply appreciated by the United States.”

One has to assume Heyman didn’t freelance this act, but the book offers no further explanation. “After that,” Heyman continues, “everything opened up for me in Ottawa. When I asked for meetings with cabinet ministers, I got them.” Gradually, a better personal relationship developed between the prime minister and the ambassador.

Vicki Heyman calls the Harper months and the Trudeau months “as different as night and day.” For instance: “The Trudeau months were warm, invigorating, and youthful from the moment Justin stepped into power as the 23rd prime minister of Canada.” When Trudeau’s three-day visit to Washington is arranged (we learn more in the book about this kind of negotiation than about any substantial policy work), Bruce describes it as “such a high point in our lives and careers. It took us back to 2008 when Obama was first elected.”

This “Camelot moment” was not to last; In November 2016, Donald Trump was elected U.S. president. The Heymans, like many liberal-minded Americans, were stunned and deflated. And in January 2017, their tenure, like that of other Obama appointees, came to an end. Trump, Bruce Heyman writes, “was about to test our relationship with our greatest ally and friend by attacking longstanding, mutually beneficial trade agreements and undermining the core values that define Canada and Canadians.” He adds, “it was beyond my worst imaginings that, as president, he would pose a threat to the sacred bond between our two countries.”

With no formal diplomatic role since then, the couple nonetheless see themselves today as “unofficial ambassadors for the U.S.-Canada relationship” and they’ve been outspoken about Canada’s virtues. Writes Bruce, “the moral compass of North America points north.”

Not all Canadians would be quite this generous in assessing their own country or its leader(s). But in the end, the Heymans’ affection for us is no small thing, not if they’re willing to so eagerly and consistently make the Canadian case to the U.S.

Perhaps, then, we can overlook the clichés. Let’s just sip our double-doubles and bask in the compliments.

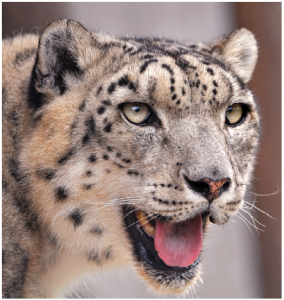

Saving the snow leopard

A completely different take on diplomacy arrives via Alex Dehgan’s The Snow Leopard Project (Public Affairs, Hachette Book Group, 280 pages, $16.65.) Set in Afghanistan, this book — part adventure tale, part policy manual and part environmental essay — tells the story of an Iranian-American scientist who travels to one of the world’s most dangerous places to research and help save scarce species, trying to preserve the natural landscape from the scars of fighting.

Conservation diplomats aren’t soldiers or aid workers or official government envoys; they’re on the ground in this particular nasty war zone to count Marco Polo sheep and find musk deer and gather bits of animal scat as they try to establish national parks in a remote, unlikely corner of the planet.

And yes, they want to find out the fate and health of Afghanistan’s fabled snow leopards — the huge-pawed, plump-tailed, mountain-dwelling felines of central Asia, under threat, as other species are, from decades of human conflict. Quick spoiler: The author never actually sees a snow leopard, but his team uncovers ample evidence that the big cats are there and being hunted, and works out innovative plans to safeguard these and other creatures so essential to restoring the country’s natural health.

Afghanistan isn’t the most obvious location to be pitching ambitious conservation projects. But as Dehgan points out, “just as Afghanistan was a crossroads of human culture and empires, it was always a biological Silk Road,” a home to some unique biogeography. “Take these fragile habitats and their denizens, add a quarter-century of conflict, and stir furiously; the result is a serious disruption of the ecosystem … our goal was to reverse this disruption.”

Dehgan’s Wildlife Conservation Society team, funded by USAID, faces the traditional threats confronting any organization in Afghanistan, such as kidnappings, IEDS, mines or suicide attacks — but it also endures the unique perils of travel by yak or horse in extreme environments, and often spends weeks under primitive conditions in some of the highest elevations on Earth.

The team, many of whom are Afghans, knows its stuff, yet still routinely runs into danger. Dehgan, for instance, is bird-watching alone one day when a stranger approaches, announcing he is Taliban. The author — an American, remember — somehow maintains his cool and keeps his eye on the birds. Eventually, his newfound acquaintance does the same.

On another occasion, travelling by vehicle to the mountainous province of Badakhshan, the conservationists accidentally veer off the poorly marked track and find themselves more than 50 feet into a minefield. “We went silent as Khoja (the experienced driver) put the car in reverse and slowly backed up, trying to follow our tracks precisely,” Dehgan writes. Afghanistan, as he reminds us, is one of the most heavily land-mined nations in the world.

Other harrowing tales are included, but Dehgan’s book isn’t simply (or even mostly) a retelling of war stories at the bar. He delves into what works — and doesn’t — for foreign aid in conflict zones; vividly describes the culture of the capital, Kabul; pens beautiful descriptions of the natural world he sees around him; and offers much-needed historical context on Afghanistan itself. He is a man partly in search of his own identity, but his admiration for Afghan people is plain as the narrative develops.

In the end, national parks do get built, thanks in part to local populations that quickly, perhaps surprisingly to Western eyes, embrace the concept of natural preservation. “The protection and renewal of wild Afghanistan, of its flora and fauna, represented a restoration of the country’s own ferocity and identity,” writes Dehgan.

And the magnificent snow leopards have a fighting chance to survive — and maybe thrive.

‘This does not have to happen again’

Greg Beckett has a much grimmer story to impart in There is no Haiti: Between Life and Death in Port-au-Prince (University of California Press, 2019, 295 pages, $37.95.) An anthropologist by training, his focus is Haiti, a country he visited repeatedly for a decade from 2002 on, probing how it is that people can live their everyday lives in a state of constant crisis, not merely day after day, but year after year.

Greg Beckett has a much grimmer story to impart in There is no Haiti: Between Life and Death in Port-au-Prince (University of California Press, 2019, 295 pages, $37.95.) An anthropologist by training, his focus is Haiti, a country he visited repeatedly for a decade from 2002 on, probing how it is that people can live their everyday lives in a state of constant crisis, not merely day after day, but year after year.

Haiti’s crisis is environmental, political and social. But while the author seeds his book with historical context, his strong narrative style emphasizes individual people — mostly men, as it happens — who work in the informal economy and with whom he becomes fast friends while meticulously studying their lives. There’s Manuel, for instance, whom he meets at a market; Manuel will become the source of the book’s title when he bluntly tells the author, “Haiti is dead; there is no more Haiti.” There’s Wilfrid, who runs a shop that becomes the locus for much of the book. There’s Alexis, whose beat-up car is his lifeline to employment, sometimes as a driver or brief tour guide for foreigners and aid workers. Their world is one of “wageless work, squatter settlements, black markets and debt.”

There are surprises woven through this book — such as the history of a remarkable forest on the edge of Port-au-Prince that activists are desperately trying to save by turning it into a botanical garden (it will later house gangs of kidnappers). There are descriptions of the markets, where “everything is sold in the smallest units. And alongside the tiny fractions of food: the slivers of soap, the lone matches, the single tablets of medicine.” This is what poverty looks like: “Everything is for sale in the city, in the city full of people with no money.”

Having survived the turbulent Duvalier dictatorship only to scratch out a living under the reformer Aristide, who will later be displaced, the residents of Port-au-Prince endure one calamity after another: poverty, gang violence, kidnappings, coups, tropical storms, mudslides and floods of epic proportions, and, of course, the 2010 earthquake and cholera epidemic that follow. Beckett speaks to his friends not only of how they survive but of what they are feeling; indeed, if there’s a flaw to his narrative it is his tendency to imbue these characters with an abstract, almost spiritual air that most humans don’t seem to have. But Beckett walks among them, and his philosophical waxing is an attempt to distil his friends’ stories into some sensible form.

One remarkable part of this book is his description of waiting for the coup (that eventually topples Aristide). Everyone knows it is coming: Street violence is mounting; there are food and gas shortages and rolling blackouts. “Waiting was just about the only thing there was to do,” he writes. When he tells Wilfrid he wants to understand the political situation, his friend responds “Ah, you would have to be Haitian.”

That Haiti should be in such constant chaos and disorder (“dezod”) seems inevitable, but for Beckett, it need not be. “I resist the dominant trope of tragedy in stories about Haiti … what happened did not have to happen and does not have to happen again,” he writes with determination. One admires his optimism, but there is scant evidence in his book to justify it.

Further reading:

There Is No Planet B: A Handbook for the Make or Break Years

Mike Berners-Lee

Cambridge University Press, 2019

288 pages, $15.45

This jargon-free primer addresses a range of questions about the fate of the planet, using a Q and A format that lets the reader skip or focus on sections according to interest. Berners-Lee spends a lot of time on the environment, but his approach is holistic, delving into subjects from food to energy to travel to modern values. Questions range from “What are the fourteen things every politician needs to know about climate change?” to “Why don’t people explode from over-eating?” to “Is nuclear nasty?” and even “How can I tell whether to trust anything in this book?” One need not agree with all of the author’s conclusions to enjoy this trove of information.

Too Dumb for Democracy: Why We Make Bad Political Decisions and How We Can Make Better Ones

David Moscrop

Goose Lane Editions, 2019

254 pages, $20.2

Humankind, notes David Moscrop, is “a clever species that routinely makes bad decisions, including political decisions, and gets stuck living with the consequences.” It’s capable of electing both an Abraham Lincoln and a Donald Trump. The question is: Why? And how can we learn to make better political choices? The book’s title provocatively implies that we may just be too dumb to get it right. Yet, as Moscrop notes, we can strive for better, and we must — for “we have never faced the risks of mass casualty or extinction by our own hands that we face now.” His recipe for how to do democracy right is a thoughtful read.

No Nation for Women: Reportage on Rape from India, the World’s Largest Democracy

Priyanka Dubey

Simon and Schuster India, 2019

320 pages, $15

India, which held national elections this year, boasts with justified pride of being the world’s largest democracy. But statistics also suggest it is one of the world’s biggest “rape capitals” too. Investigative journalist Priyanka Dubey explores that darker side of the subcontinent in this uncompromising account of often unreported stories about abused women and cultures that encourage sexual assault. Over six years of travel through her country, the Bhopal native asks whether India is making meaningful progress on respect for all, and shares thoughts about how it can do justice not just to men, but to women, too.

Christina Spencer is the editorial pages editor of the Ottawa Citizen. She holds a master’s from the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University, and is a past winner of National Newspaper Awards for international reporting and editorial writing.