Sailing on Adventure Canada’s Greenland and Wild Labrador Expedition gives new meaning to the phrase “peak experience.”

Besides hiking along the base of Canada’s highest mountains east of the Rockies — northern Labrador’s Torngat Mountains’ peak altitude is 1,652 metres — we walked along its fjord cliffs and rode Zodiacs into the narrow fjords.

During the 15 days aboard the Ocean Endeavour, with outings to Nuuk, Greenland, and the parks and villages and cities of Newfoundland and Labrador, we passed polar bears and black bears, Arctic foxes, seals and minke and narwhal whales. We even had the company of a hitchhiking peregrine falcon — staff nicknamed him Perry — who took up temporary residence amid the ship’s lifeboats.

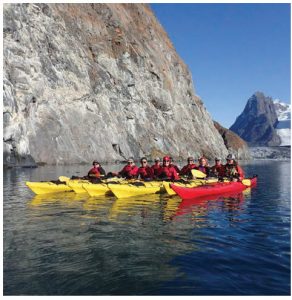

And, the eight people who chose to go kayaking, paddled (not too close, in case a breakaway piece of ice swamped us) to a small glacier and around a small opalescent blue iceberg that “calved” off the glacier and was floating free.

Our kayak guide scooped up a thousands-year-old piece of floating glacier ice, slipped it under his kayak’s netting and supplied drinks with extraordinary ice cubes that night.

And then there was the polar dip: A few dozen guests and expedition specialists dove off the ship, safely attached to a tow rope in case the cold took their breath away. (They all returned to the ship under their own power, breathing intact and exceptionally invigorated.)

“Follow the route of Leif Ericsson from Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, to St. John’s Newfoundland via coastal Labrador,” is how Adventure Canada describes this trip. It is one of many that the expedition company offers, ranging from the Arctic to Eastern Canada to Haida Gwaii’s islands off British Columbia’s coast, to Central America.

The chartered Toronto-to-Greenland flight landed in Kangerlussuaq, just north of the Arctic Circle where Ocean Endeavour took on the nearly 200 guests.

The next days featured a Zodiac or kayak trip to the Evighedsfjord Glacier — sadly much smaller after a very few years of melting — and the Kangerlussuatsiaq Fjord of western Greenland.

Forewarned by expedition leader Jason Edmunds, a Labrador-born Inuk, that the itinerary was liable to change quickly, sure enough, near gale-force winds and high waves did force the captain to seek safety in Nuuk harbour for two days. This Danish-Inuit city and the administrative capital of Greenland is well supplied with stores, great beer and local foods, specialty shops for local arts and designer clothes, often made with skins or pelts, along with modern European household wares.

The Danish krone is the local currency. Denmark, which continues its semi-colonial relationship with Greenland, reportedly contributes two-thirds of government revenue. Greenland benefits economically and socially, ranging from medical and social services to jobs and education in Denmark for qualifying young people. A 2009 referendum granted more autonomy to Greenland; eventual independence is the wish of some of its people.

One of them is Tina Kuitse, an Innu from Nuuk who grew up on Greenland’s east coast in a hunting environment. She wants a future different from a “copy-and-paste” Danish system. “Even though we have a [legislative] majority, we see a huge landing strip in the middle of everything. Even though we yell we don’t want an airport here, the government is still working on it now.”

Though grateful for the opportunities of city life and her education — she’s finishing her master’s at the University of Greenland — she prefers living in an isolated place. Inuit culture is shy and quiet, she says, and Europeans are “very talkative and very communicative.

“We grew up with that silence at home.” Four generations, she says, “15 people and nobody would say anything. That’s not even awkward to us. It’s just comfortable.”

The two states co-exist with their wildly unequal land area ratio of 50:1, Denmark is 43,000 square kilometres; Greenland, the world’s largest non-continent island, is 2.17 million kilometres. (Ontario, for comparison, is 1.1 million square kilometres.)

Resource-rich, its rare-earth metals, crucial for electronic devices, have drawn China’s interest and triggered U.S. President Donald Trump’s sudden and frostily received offer to buy the island.

A few hours’ walk will take you around Nuuk, with its modern Katuaq Cultural Centre, a shopping mall and small homes, which unexpectedly feature plant-filled sun porches. The local meat market consisted of large tables with whale blubber, reindeer and caribou meat, along with salmon and other fresh fish.

The highlight is the superb Greenland National Museum and Archives, rich in historic photographs and even an old black-and-white locally acted film depicting this fishing-hunting culture, pre Western influence. With its displays of ancient deities, traditional dogsleds, kayaks, housewares and gorgeously decorated clothes, the museum has a separate wistful display. There, three women and a six-month-old baby, mummified by permafrost in a cave and said to be the best-preserved humans in North America, are laid out in their 500-year-old burial clothes. They were part of the family grouping of six women and two children discovered in 1972.

Nuuk housing is in too-short supply, and is often controlled by businesses that rent dwellings for their workers. There is no private ownership of land and homes. You may be caught off guard by the barracks-like long buildings — four-storeys high, with tiny apartments and balconies where many of Nuuk’s Inuit live as part of the Danish government’s way of providing them shelter and Western services. In contrast to Canada, where decent shelter is not provided to any sufficient degree — and certainly is often cramped and sub-standard — it is hard to imagine the land-living, land-loving Greenlandic Inuit in these apartments. As with Canadian and other Indigenous peoples moved off the land to city apartments, or unsuitable or economically unfeasible settlements, suicide rates are much higher than in the general population.

Labrador’s Torngat Mountains National Park

The overnight trip southwest to Labrador, across the Davis Strait, had some steep pitch-and-toss moments before landing in the beautiful Torngat “Place of Spirits” Mountains.

If you’ve never seen the Torngats, you may have wondered at the swirling colours that Group of Seven painter A. Y. Jackson gave to his 1930 canvas Labrador Coast. Standing there in late September, the sharp contours and grey peaks are offset by the vivid yellow, red and orange autumn plants, many bearing delicious berries, that carpet the low slopes. (In contrast to daily buffet breakfasts and lunches, and formal sit-down dinners, we were treated to a country-food snacking buffet of raw seal, dried caribou, whale and char, along with fresh-picked wild berries.)

Torngat Mountains National Park is intentionally a wild place. Beloved for its contrast with many of Canada’s national parks with their stores, golf courses, playgrounds and other imports of urban life, it is unspoiled, raw and utterly without buildings. This visit was widely seen as the trip’s highlight.

As vice-president of Parks Canada’s Northern and Western Parks, Newfoundlander Jeff Anderson was involved in the creation of the 9,700-square-kilometre award-winning park. It formally became a park in 2008 when the Nunavik Inuit Land Claims Agreement came into legal effect. Toby Andersen, chief land claims negotiator for the Labrador Inuit Association, presented the park as “the Inuit gift to the people of Canada.”

Jeff, recently retired, was free to answer the question he had long dodged: “With all the parks you have been in charge of, which is your favourite?” It’s the Torngats, which he saw to completion with the revolutionary underpinning that it was to be, and now is, a 100-per-cent Inuit-owned and -run park. For example, you can’t visit it without the protection from Inuit who serve as bear guards.

Wayne Broomfield, assistant expedition leader, formerly managed and operated the Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station and now works in the Arctic and Antarctic for Parks Canada. He described the park as an emotional gathering place for elders who return to visit the lands from which they were forcibly relocated. The youth program brings young people who learn drum-dancing and throat-singing and to cook traditional foods on heated rocks, as their ancestors did.

The staffed base camp and research centre is in Kangidluasuk (St. John’s Harbour), just outside the park’s borders. It offers a full-service kitchen and dining, visitor tents, (or you can bring your own), canvas structures, bright-coloured plastic-domed pod structures with lights, a bed and heater for the seasonal summer tourists season. (https://thetorngats.com/)

Nain

Nain, a settlement begun in 1771 by German Moravian missionaries, still carries their influence, which includes a charming, if unexpected, welcoming committee of a uniformed brass band playing hymns to the visitors. Nain is the administrative capital for the Nunatsiavut government. The result of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, it is the first Inuit region in Canada to be a law-making, self-governing entity, even as it is part of Newfoundland and Labrador.

L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland

An artifact-rich museum serves as the entrance to L’Anse (Cove) aux Meadows, at the tip of Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula. This UNESCO site, only discovered in the 1960s, marks the first Norwegian Viking landing site in North America, about 1,000 years ago, perhaps as a base for explorations to New Brunswick and the U.S. There, Vikings set up a community and left behind artifacts, including iron tools, marking their stay. It is a short walk to the shoreline, where rebuilt sod dwellings stand and where lively local actors tell jokes and tales as they make pancakes on the fire, served with partridge-berry jam.

Terra Nova National Park

A fitting last excursion was walking in the lushly treed ocean-front 400-square-kilometre Terra Nova National Park. Wildlife includes coyotes, moose, caribou and black bears, red foxes, beavers, red squirrels, snowshoe hares, pine martens and minks, along with such birds as bald eagles, puffins and ospreys. The park lists its species at risk: American marten, little brown bat, red crossbill, boreal felt lichen, blue felt lichen, northern long-eared bat, olive-sided flycatcher, rusty blackbird and short-eared owl.

St. John’s

Last stop, disembarkation at St. John’s, Nfld. The seamanship needed to pass through narrow St. John’s Harbour (“threading the eye of the needle”) provided time to enjoy the skyline and famous candy-coloured buildings that rise up its slopes.