Their first-hand stories are funny, vivid, scientific, sometimes distressing — another kind of exploration.

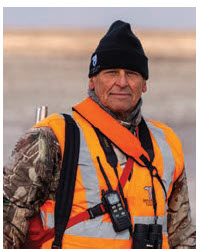

Dylan White, wilderness and wildlife guide, has worked on 150 projects for government, academia and private groups. His Arctic mammal talk included black bears, grizzly and polar bears, all of which can interbreed to produce, in the case of the latter two, “pizzlies” or “grolars.”

He often gets up close and, apparently, too personal. He settled himself outside an Arctic fox den where mom and pups were living. During the 45 minutes he was there, the pups emerged to join their father, who lazily looked at Dylan every few minutes.

“The pups were running around, having a great time. Suddenly, mom comes out of the den, sees me, scrams, bites the male and rushes all the pups into the den. It’s like ‘you had one job, man. One job.’ He just failed so badly.”

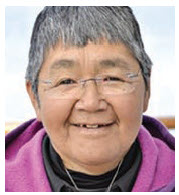

Maria Merkuratsuk, born in Nain with eight siblings, only received schooling through Adult Basic Education. She earned diplomas in social work and heavy equipment operation and instructs on such traditional skills as preparing sealskins, sewing and the Inuktitut language. As a member of the Canadian Armed Forces, 5th Canadian Ranger Group of Newfoundland and Labrador, her duties include patrolling, guiding, providing emergency services and mentoring young people.

She gave a recital of life behind her biographical note. It started in happiness. “It was the most beautiful life ever. The fresh air, the ground, the rocks, the high mountains. I picture my mom and dad, my siblings and the people that were there. Nothing of the world. Nothing of speaking English.”

It ended in a protracted and ongoing struggle to heal herself. Sexually abused by three different men when she was a young woman (“at the time I thought it was normal.”) Alcoholism, drug addiction, mental illness and attempted suicide followed, before the gargantuan turnaround she achieved. When her first granddaughter was born, 24 years ago, she stopped drinking. “Sometimes I have to get away because I can smell alcohol and I am so tempted. Sometimes I think I get drunk from the smell.

“I‘ve learned that all the hurt came from the Hebron relocation. It all goes back to there.” Her father was a fisherman and they lived in a tent in the summer. “We were really poor, but we had it so rich. She remembers the caring father who made tea sweetened just so for his children, and the father who, after the forced relocation from Hebron, became an alcoholic, violent with his family.

“My counsellor told me it wasn’t my fault when I got sexually abused, when I got raped. Most of my life, I felt that I’m doing something wrong and I’m tired of that.”

No dry eyes onboard that day, hers or her listeners’.

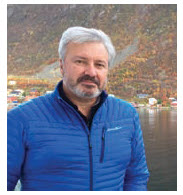

Randy Edmunds earned a fishing master’s certification and fished such species as salmon, char, cod and shrimp. He and his wife, Lori, owned a small hotel and tour boat operation. He recently retired from his eight-year term after representing the Torngat Mountains in the provincial legislature.

He gave a scientific talk on the mystery of the disappearing George River caribou herd whose population dropped from 800,000 in 1999 to 5,500 today. It’s the same over the Canadian and the circumpolar region, with only the Porcupine Herd of the Western Arctic doing well, he says. He mentioned two possible reasons: Sampled caribou reveal a thin membrane between fur and meat itself, which though still good for human consumption, also coats reproductive organs. Another possible cause is the warming climate, producing edible vegetation too soon for the still-nursing calves. There is a ban on hunting this key food source and intensifying studies between Indigenous hunters and (other) scientists.

Derrick Pottle — Labradorian Inuit hunter, trapper, carver — prefers the mix of Western and traditional life. He said in the old days, the Inuits’ hands were crippled with arthritis, they were dying in their 40s, life was hard during weeks-long hunting trips to feed themselves.

But he wants to preserve it, too, and teaches bear safety and survival skills to the public. The lining of each sky-blue Adventure Canada waterproof jacket bears this quote: “Derrick Pottle, son of Labrador: Culture has to be practised, to be strong.”

He draws sharp contrast, though, between “sailing through some of the most pristine areas anywhere in the world” and the reality. “If you scratch the surface a little bit, there is a whole other story that is not being told” near the Torngat Mountain Base Camp.

It’s the site of a former Cold War installation of the DEW (Defense Early Warning) Line. “When the personnel left, there were so many contaminants that we couldn’t eat bottom-feeding fish, or eat bird eggs due to high levels of PCBs.” In Hopedale, the site of another radar installation, even today, he says, in some subdivisions, people have had to move because of high contaminants oozing out of the ground in people’s backyards. Cancer rates, too, are elevated.

In the Muskrat Falls project, he says, “they forgot to do an environmental impact survey that went beyond the mouth of the river. Residents there have mercury levels four times [those of] Health Canada’s recommendations. It’s also a major habitat for ring seals that we eat – they forgot to put seals on the advisory list.”

In some areas of Labrador, people were advised to not eat more than one fish meal a week of fish due to high levels of methyl mercury.

Voisey’s Bay Nickel Mine is an early example of business relations between resource companies and the Inuit. (Labrador-born Tom Paddon is the brother of Dave Paddon and part of the two generations of Paddons who provided medical services to Labrador communities (please see story on forced relocation). Dave, a retired helicopter and Air Canada pilot, is an author and humorist who serves as an archivist of family documents.

Tom is chairman of Baffin Island Iron Mines, described as “Canada’s newest and northernmost iron ore mine.” He presented a detailed template for a resource project’s success in Indigenous lands. Many elements were part of the agreement he had previously helped to develop between Labrador’s Nunatsiavut government and Innu Nation for the Vale Inco Voisey’s Bay Mine — especially necessary after the 1997 RCMP arrests triggered violent protests over unresolved Innu-Inuit land claims.

A report consolidated the key elements for successful negotiations: Early consultations, environmental assessments, training, employment, compensation and revenue arrangements, as well as respect, protection and support of social and cultural values of the Inuit and Innu.

Lena Onalik grew up in Makkovik and spent summers at her grandparents’ fishing grounds processing fish for the fish plant. Graduating with a major in archeology/anthropology and minor in Aboriginal studies from Memorial University in St. John’s, she was briefly chief archeologist for the Nunatsiavut government.

Her family was deeply affected by relocation. As she spoke, she was standing among the mounds in Hebron, collapsed sod homes that dotted the shoreline and where her grandmother lived and her mother was raised.

“Because of the relocation from Hebron, and of being Inuk, my mother never wanted me to be isolated because I was an Inuk. She wanted me to be accepted and made me feel that, because I was ‘dual’ — my dad’s ancestry is white — I am just as good as anybody else. She felt so much shame for being, as she would say, an Eskimo.”

Pregnant at university and with two first cousins in the foster system since a very young age, she cared for her sister, who is 15 years younger and who has partial fetal alcohol syndrome. She continued her university studies while caring for her own baby. “It was hard. It was worth it. The cycle has to stop. It doesn’t need to continue with me or my children. Enough is enough.”

She plans to return to archeology. Today, though, she has three young sons and does homecare for its flexible schedule. She and her husband, a carpenter, want their sons to be connected to the land. “I think it is so essential for future generations.”

Heather Angnatok is a Labradorian Canadian Ranger, chairwoman of Nain Women’s Shelter, traditional skills educator and outdoorswoman who makes traditional plant-based medicinal products.

She says Newfoundland gets the most funding and its needs met due to its larger population. “The further north you go, the less they listen to us — that’s just how it feels.”

For example, Labrador used to have two airlines and two ferries — one for goods and one for cars and passengers. Air Labrador is no longer running, leaving only Air Borealis. And the two ferries are gone, replaced after the Newfoundland government’s decision to provide a large ferry.

“They [government representatives] came into our community and said: ‘This is what we’re doing for you. We’re giving you a brand-new ferry. It’s going to be bigger; it’s going to be brighter; it’s going to be more efficient.

“We gave them all our concerns and we asked ‘Why didn’t you consult us first? We know what we want. We know what would work.’ They said, ‘No, we know what we’re doing. [Now] we have that ferry and it’s,” she gestures, “two thumbs down.”

Sometimes, due to weather, the ferry service is stopped — no service whatsoever. “It affects store owners, food, lumber — they don’t have any products.” People depend on the ferry to cross the Strait of Belle Isle that separates Labrador from Newfoundland.

One key loss, she says, is that the ferry has changed routes so that Lewisporte, where a grocer would box up more economical bulk orders of food, is no longer a ferry stop. Public criticisms focus on a top-heavy and potentially poor design that renders the ferry unable to function safely in the high winds that often occur.

Donna Jacobs is publisher of Diplomat magazine. This trip was at the invitation of Adventure Canada.