A Maru Public Opinion poll taken earlier this year showed that an overwhelming majority of Canadians now believe that domestic extremists and terrorists are more threatening than foreign ones. The poll did not ask Canadians what kind of extremists or terrorists they are most worried about. But an earlier poll in 2018 conducted by Angus Reid did. It found that, on average, Canadians were more concerned about “radical Islamic terrorism” (54 per cent) than “white supremacist terrorism” (44 per cent).

If the earlier poll is a bellwether of prevailing public sentiments, which admittedly may be changing in light of recent events, the attitudes of Canadians do not differ all that much from those of their own government. Public Safety’s 2018 Report on the Terrorism Threat to Canada — the most recent publication of this sort — asserts that “the principal terrorist threat to Canada and Canadian interests continues to be that posed by individuals or groups who are inspired by violent ideologies and terrorist groups, such as Daesh or al-Qaida.” The report, however, runs counter to a growing body of scholarly literature and investigative reporting that suggests otherwise. According to Barbara Perry and Ryan Scriven’s 2015 environmental scan, right-wing extremists have committed more violent attacks on Canadian soil than any other kind of terrorist. And since 2015, Perry has observed a 30-per-cent increase in right-wing extremist groups, totalling more than 130. The threat is real, rapidly evolving and relatively understudied.

The problem

In recent years, a series of attacks by right-wing extremists have dominated headlines. In June 2014, Justin Bourque killed three RCMP officers and injured two others in Moncton, N.B. Bourque was apparently motivated by extreme anti-law enforcement and anti-government beliefs. Hatred of Muslims led Alexandre Bissonnette to shoot 6 worshippers, killing them instantly, and injure 19 others at the Islamic Cultural Centre in Quebec City in 2017. In 2018, 10 people were killed and another 16 wounded when a misogynistic, involuntary celibate (Incel) movement follower, Alek Minassian, deliberately plowed his van into a group of pedestrians on Yonge Street in Toronto. Another individual who took inspiration from Minassian’s attack stabbed a woman 35 times and injured her baby in an unprovoked attack in June 2019 in downtown Sudbury. And most recently, a military reservist, Corey Hurren, rammed the gates of Rideau Hall with his weapon-loaded truck in an effort to arrest the prime minister during his daily pandemic briefing to Canadians. Hurren was angry about losing his job and worried that Canada was becoming a communist state. It was later discovered that he had an affinity for browsing and posting far-right content and perpetuating conspiracy theories about the Canadian government.

The unruly mob of “thugs, insurrectionists, political extremists and white supremacists,” as U.S. President Joe Biden referred to them, who stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in an attempt to reverse Donald Trump’s defeat at the polls, is the latest manifestation of what some see as a growing global pattern. As United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned in February 2021, the threat is “transnational” and the “No. 1 internal security threat in several countries.” He also urged a “global co-ordinated action to defeat this grave and growing danger.”

Attacks by far-right extremists, however, are not a new phenomenon or limited to Canada and the United States. In August 1980, a splinter cell of far-right extremist group New Order set off a bomb in the train station in Bologna, which killed 85 people and injured hundreds more. The same year, neo-Nazis detonated a series of bombs at Oktoberfest celebrations in Munich, Germany, killing 13 people and wounding more than 2,000 others. The Oklahoma City bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Building in 1995 killed 168 people and wounded 600 others.

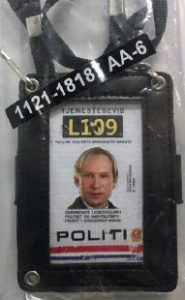

In Norway on July 22, 2011, Anders Behring Breivik, a right-wing extremist, detonated a car bomb in Oslo’s city centre, which killed 8 people. He then drove to the island of Utøya where a large group of young Norwegians was attending a summer Labour Party youth camp. Masquerading as a police officer, Breivik gunned down 69 of them during his rampage. The mass shootings at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, in March 2019 by a self-styled white supremist killed 51 people and injured 40 others. A far-rightist gunman killed 2 and seriously injured several in Halle, Germany in October 2019 and could have killed many others had law enforcement officers not intervened and prevented him from setting off bombs at a synagogue in the city. Swedish neo-Nazi, anti-racist groups have also carried out repeated bombing attacks against refugee shelters over the years in a country that has historically been viewed as a haven for refugees, with generous asylum and immigration policies.

Global trends suggest that the number of right-wing attacks is only rising. One study showed that from 2014-2019, there was a threefold increase in the number of attacks carried out by individuals associated with such groups or movements globally. And according to the 2020 Global Terrorism Index, far-right attacks in North America, Oceania and Western Europe have increased by 250 per cent since 2015. There is also disturbing evidence that some of these groups are forging transnational ties. American neo-Nazis have trained and fought in Ukraine and Russia. Likewise, “copycat” attacks and tactics have spiked. In 2019 alone, the perpetrators of three separate attacks, Christchurch, Halle and Poway (where a man entered a synagogue on the Jewish holiday of Passover and killed 1 congregant and injured another 3) videoed or livestreamed their assaults and uploaded them to social media platforms and extremist forums alike. Similarly, some right-wing extremists, such as Anders Breivik, have turned to penning a manifesto, which expert J.M. Berger explains is a “combination of terrorist how-to tactics with propaganda and incitement.”

Like other radical groups, right-wing extremists use traditional social media outlets to recruit followers and promote violence, but also a variety of non-mainstream platforms such as Gab and Voat for communication and radicalization. They are also collaborating online to raise funds and disseminate their literature. According to a 2020 report by the Institute of Strategic Dialogue, there are more than 6,600 online channels where Canadians were involved in spreading white supremacist, misogynistic and other radical views. This makes Canadians more active, on average, than users in the U.S. and the U.K.

Framing and responding to the threat

A global, co-ordinated international response has been urged by some, including Guterres, but that may be easier said than done as right-wing extremism lacks a global coherence and because the tactics, actors and motivations can range quite considerably depending on the country. According to Public Safety Canada, right-wing extremists have proven to be particularly difficult to thwart, largely because they are sporadic and opportunistic and because the perpetrators often do not have organizational ties. Many of these extremists are active online, using chat forums and networks to exchange ideas, rather than promoting open violence towards a specific group. And when violent attacks do occur, they appear largely to be unplanned and carried out by individuals of their own volition rather than being instructed by a foreign-based organization.

Other shared characteristics of these groups include identity narratives that stress the survival of the nation, subjugation of and violence against women and the promotion of traditional stereotypical gender roles (that is, women as mothers and housewives). They also can have a strong anti-refugee and anti-immigrant orientation. As the Anti-Defamation League points out, “There is a robust symbiosis between misogyny and white supremacy; the two ideologies are powerfully intertwined. While not all misogynists are racists, and not every white supremacist is a misogynist, a deep-seated loathing of women acts as a connective tissue between many white supremacists, especially those in the alt right, and their lesser-known brothers in hate such as Incels, MRAs (Men’s Rights Activists) and PUAs (Pick Up Artists).”

The loose nature of right-wing extremism has opened a debate on how to properly define and respond to these challenges. The UN counter-terrorism committee suggests that “far-right or racially and ethnically motivated terrorism” has “fluid boundaries between hate crime and organized terrorism.” It is “not a coherently or easily defined movement, but rather a shifting, complex and overlapping milieu of individuals, groups and movements (online and offline) espousing different but related ideologies, often linked by hatred and racism toward minorities, xenophobia, Islamophobia or anti-Semitism.”

Similarly, the London-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue identifies a wide range of different categories of right-wing extremists that include white supremacists and neo-Nazis, racist skinheads, anti-authority activists, lone actors and what they refer to as “ideologues” or “gurus,” the “alt-right,” the “manosphere” and anti-Muslim groups. The latter category is characterized by groups that exude an obsessive disdain towards Islam.

Daniel Kohler, director of the German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., points out that “One problematic issue connected to identifying and adequately classifying right-wing terrorism is the lack of clarity among the different concepts used to describe this form of political violence. In fact, many incidents of right-wing terrorism have been analyzed under the concept of “hate crime,” which does share a number of similar characteristics with terrorism. A hate crime — defined as “a criminal act that is motivated by a bias toward the victim or victims’ real or perceived identity group”— can include, for example, the desire to “terrorize a broader group” or to create a specific intimidation, including through hate speech, which has been described as simply another manifestation of terrorism.” In Canada, for example, 2,073 criminal incidents motivated by hate, a 60 per cent increase, were recorded between 2014 and 2017. With more than 780 of these incidents being violent, it is likely, according to the University of Calgary’s Michael Nesbitt, that the severity of Canada’s right-wing extremism problem is much greater than what is being reported.

During the Trump administration, efforts to promote transatlantic co-operation floundered on definitional issues because U.S. officials refused to use the term “right wing terrorism.” Instead, they preferred “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism” (the term used by the FBI and Homeland Security) or the State Department’s favoured “racially or ethnically motivated terrorism.”

The response of many countries to the problem has also been patchy, unco-ordinated and increasingly politicized. Law enforcement officials and the intelligence community have been accused of not paying sufficient attention to the threat posed by white supremacist and other racially motivated extremist groups. In response, some officials have argued that terms such as “right-wing terrorism” legitimize these groups by placing them on the political spectrum while further polarizing political attitudes in a highly charged domestic political environment. This has been especially true in the U.S., where any kind of crackdown through the introduction of new laws and regulations collides with the constitutional protection of free speech under the First Amendment and curbing civil liberties, a concern that was repeatedly and vigorously raised by Muslim and human rights groups in the “war on terror” during the Bush administration. In Canada, the challenge is further compounded by the tendency of federal officials to view the actions of such groups through the prism of hate crimes and as a local or provincial policing responsibility.

Looking ahead

Despite the growing need for a co-ordinated national and international effort to confront right-wing extremism, other threats in Canada, the U.S., and much of the world persist. According to the Global Terrorism Database, 95 per cent of the terrorist incidents in South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa remain religious-based. And despite a recent and precipitous decline in terror attacks due to recent gains in the war against ISIL and Boko Haram, the situation remains volatile. Like right-wing extremists, foreign-based terrorist organizations have become master recruiters. The latter are usually more organized, and have the institutional and financial might to support large transitional attacks.

Furthermore, left-wing extremism is another threat that has garnered considerable attention as of late, especially with mass protests and riots that have turned violent in the U.S. Usually centred around an opposition toward imperialism, colonialism and capitalism; support for communism, anarchism and animal and environmental rights; and proponents of black nationalism, the number of left-wing extremist attacks has ebbed and flowed since the 1960s. In Canada, one infamous example is the Front de libération du Québec, a Marxist-Leninist terrorist group that promoted — through violence — social insurrection and Quebec independence throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

In the U.S., the threat of left-wing extremism remains lower than the right, but higher than that of religious-based groups. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in 2019, far-left terrorists committed 20 per cent of attacks and plots in the U.S., compared to 67 per cent by right-wing extremists, and 7 per cent by Salafi-Jihadists. As they have with the threat faced by the right, Canada and the United States have struggled to adequately define the problem, target the necessary actors and co-ordinate an all-encompassing national and international response. Contemporary left-wing extremist groups are less organized than their counterparts, but it would be a grave mistake for decision-makers in any country to overlook the potential of future violence.

On Jan. 25, 2021, fewer than three weeks after the storming of the U.S. Capitol, members of Canada’s Parliament voted to label the Proud Boys, along with three other extremist groups, a “terrorist entity.” Adding these groups to Canada’s official terror list, joining the ranks of Al Qaeda, Boko Haram and the Taliban, among others, is a significant step in the right direction. In addition to the criminal and financial sanctions these groups may face, the move sends a signal that official attitudes may be shifting, although Canada’s Public Safety Minister Bill Blair was himself at pains to deny that the decision was politically motivated. Canadian officials have also gone out of their way to eschew the political labelling of such organizations — both on the left and the right — by referring to them as “ideologically motivated violent extremist groups.” In the disruptive temper of our times, that may indeed be the wisest course.

Fen Osler Hampson is Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University and president of the World Refugee & Migration Council. Kevin Budning is a PhD candidate at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.