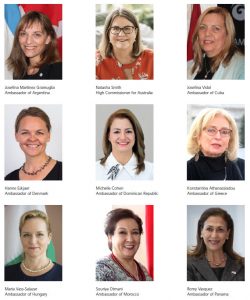

With the help of EU Ambassador Melita Gabric, Diplomat organized a panel for its usual Q & A with editor Jennifer Campbell. The group — all women heads of mission — has a formal organization, which Gabric chairs, and it meets regularly to discuss common areas of interest. Today, there are 29 women who are heads of mission in Ottawa; four more based in the U.S., but accredited to Canada, and six women chargé d’affaires. And, in recent years, major posts, including those of the ambassador of the U.S. and France and that of the British High Commissioner have been filled by women for the first time. Diplomat wanted to talk to these women about their unique careers, the proverbial glass ceiling women encounter in the workplace and the plight of women in their countries. What follows is a transcript edited for length. (Editor’s note: Moroccan Ambassador Souriya Otmani wasn’t able to join the panel because of timing, so she answered our questions the following day.)

Diplomat magazine: Can you talk about a situation in your career where you met the proverbial glass ceiling and share what you did about it and how diplomatic training helped you to resolve it? And finally, what tips would you offer for women following in your footsteps?

Melita Gabric (EU): One thing I would say is that the glass ceiling is difficult to see, which is to say that it is difficult to pinpoint a situation where one was denied a promotion due to gender, or some other sexual discrimination or circumstance. I would say it is important that women pre-emptively empower themselves as much as they can. I would definitely put a premium on education, on developing skills and competencies, and that includes diplomatic competencies because this helps with resilience, freedom of choice and manoeuvring space and, at the end of the day, it can help with moving that ceiling further up and ideally, down the road, removing it altogether.

Hanne Eskjaer (Denmark): I was thinking about a personal experience and was inspired by an example where I think we managed to break the glass ceiling. It was a few years ago and I was four months pregnant and posted in New York and I was up for a change in position. I really wanted to become the deputy in Prague because [it was joining] the EU. Everyone told me, ‘Who would hire a four-month-pregnant woman for a deputy position?’ I went for it and I applied. It was an old ambassador, it was his last post, a very proud man from the old school. Everyone said this was not going to work. But he decided to invest in the long term. He said, ‘Yes, I see your talent, I want you on board. I know that you won’t be there in the beginning, but I want you on the team.’ It was a combination of him looking in the long term and it was me believing I was the right choice for him. And the last thing was that my husband and I decided we would split the leave into two so when half of it was over, I went back to work and my husband took parental leave. This is not just our personal choice for a family. This is because the system facilitates the husband taking part. It’s a mixture of personal choice, education and the systems in place to facilitate this equal distribution of parental leave.

Natasha Smith (Australia): There’s a phenomenon that I call the lonely room. Rather than glass ceilings — which I have observed and seen and had some women reach down through that ceiling and pull me up, and one or two who put their stiletto on my forehead — there’s the phenomenon of being the only woman in the room, or one of very few. I think we focus on the ceiling; it’s a very good metaphor, but I think the challenge of when you get there, how lonely it can be is [worth noting.] I certainly experienced this at various stages in my career and frankly, among my memories of where I was more junior, I was often the only woman and the youngest in the room as well. That can be very intimidating and I don’t think it’s only women. Indigenous colleagues say the same thing. Be true [to] yourself and you’ve got to feel intimidated on the inside, not the outside. I worked on water and sanitation in Indonesia and I was often the only woman and I can still remember a formal dinner with the Dutch ambassador and I was youngest and the only woman and they didn’t know what to do with me so they sat me next to the host and it was brilliant. If I’d been a man, I would have been down by the door to the kitchen and I was able to use that [seat] to my advantage. I think we can get hung up on the glass ceiling. I think it’s also the lonely room we need to think about.

Romy Vasquez (Panama): I’m the only one here who’s not a career diplomat. I was in the same situation in 2004, when we were 8 per cent [of 56 head of mission positions in Panama’s diplomatic corps] but today we’re not much better at only 22 per cent and they’re not the best positions or destinations. When we become the first woman at the White House, that will be a change. When I went for the interviews, I had the approval of the ministry and the president and they asked me to go to every government department to show what I could offer. This was an internal decision because they wanted to see how I would respond as a businesswoman to the diplomatic environment. I managed to introduce myself as an asset [because of my negotiation skills.] I think you have to learn to deliver the message of what it is that you can really do well.

Maria Vass-Salazar (Hungary): I think there’s a larger picture. Looking at diplomacy and women in diplomacy back 20 or 30 years, the picture used to be that men are diplomats, women are secretaries and that has changed a lot. There are more women altogether on our staff than men. [For me,] starting in the foreign service, the key elements were competence and confidence. In situations that are overwhelmingly male, you need the confidence without the arrogance. It’s a skill diplomats should acquire to really excel. I didn’t really experience difficulty or discrimination, but that’s the evolution of acceptance of female diplomats in the diplomatic service.

Josefina Vidal (Cuba): I haven’t had to overcome any obstacles during my professional career. The Cuban foreign service has done a great job in the last 25 to 30 years. We come from a past when the ministry was predominantly male for many years. Now 44.6 per cent of all officials at the foreign ministry are women. We still have some work to do in terms of decision-making positions, where we are just 29 per cent. In the head of mission positions, only 31 per cent are women. We don’t have a system of quotas, but there is a policy. Anytime a minister makes a proposal about who he believes is the best person to be appointed as a director-general or ambassador, he has to propose at least two names, and the balance of gender and race has to be included. This policy has been offering important results. My advice [is] study a lot, work very hard, become an expert in an area of specialization. Defend with conviction and confidence your points of view, but at the same time, listen to others and respect your colleagues.

Konstantina Athanassiadou (Greece): I agree with what has been said. I was thinking what sort of [story I could share]. There are many, but I tried to find one that was a bit funny. I knew from Day 1 when I entered the ministry that it was very competitive. I was always trying to do my best. I had to do a double effort in order to become the very best.

Now I’ll tell you the funny episode. I was in Geneva and Greece was going through a review concerning the position of women in Greece. I was not present, but the permanent representative was. I was at the WTO, dealing in quotas in sugar and transport and things like that. At a certain point, there was an alarm on my mobile asking me to come over. I asked if I could just text them or send a note; he said no. So I went there and when I entered this committee, the permanent representative said, ‘Here is an ambassador,’ because the point of the committee [was to charge us with not having] enough women in top positions. I [felt like] I was a bear in a circus. I said, ‘This is me, this is a Greek ambassador, you can’t say we don’t have women ambassadors.’

Josefina Martinez Gramuglia (Argentina): I remember being at the United Nations and I was part of the Security Council team when Argentina was a member and I was very much pregnant, so I couldn’t fit into the seats at the informal meetings. At some point, I had to ask for a special seat on the side. They had these little desks and I couldn’t fit. Talk about trying to modernize structures [laughs.] I’ve had a couple of [glass ceiling] situations, most commonly when you work for a long time on strategic files and it’s finally the time to pitch to the authorities. From time to time, I faced the doors closing for me, being the most experienced with the issue at hand, but I wasn’t able to pitch to the authorities. I tried to persuade my colleagues of the importance of being heard and my perspective and it didn’t work. How did my diplomatic training help me? I did quite the opposite of what diplomatic training would say and I challenged the norm. I couldn’t accept the status quo of being the lower rank, and not able to present my ideas. At some point, I decided to be deliberately an advocate for change and as many of my colleagues mentioned, I worked harder, I worked better and put together fresh ideas.

It was kind of a risky move, but it worked. If there are any tips for women, I would say never settle, keep pressing for inclusion, don’t wait for men to invite us into the foreign policy process. We have to look for affirmative action, look for special training programs, seek mentors for advancement in our careers and seize every opportunity that presents itself to you because you miss 100 per cent of the shots you don’t take.

Michelle Cohen (Dominican Republic): We are here because we have seen that glass ceiling at some point. I’ve broken that ceiling every single time I’ve been a candidate for a position or a place in power.

There are two things [required] — dedication and extensive training. I was born in a very small insular country in the Caribbean and Antilles. The pace of life was very slow. The Dominican Republic was a country that had 5.2 million inhabitants who were isolated from the rest of the world with very few opportunities for growth, especially for girls. The chances of being something or getting to be someone were very [slim] and you were trained to be a perfect housewife. I had a bigger view because I grew up outside the island. I went away very early. When I got back, after finishing high school, I was clear on what I wanted to do. When I was 21, I ran for a position at the United Nations Development Program. I faced being a woman and a young person. I got the position, partly because one of the [interviewers] who was an older, respected lady, decided to give me the opportunity. She decided that my energy was the reason I would be able to do the job.

Romy Vasquez (Panama): Regarding tips, all of you have mentioned so many and I would add to become a mentor for another colleague. Also, in order to break that ceiling, we need more women at the centre of the international agenda. If we don’t have more women, we will not be able to push the necessary policies and implement the changes. We need to become speakers and move forward and talk about it on social media and share that idea.

Souriya Otmani (Morocco): I consider myself a lucky woman who didn’t face any challenges of that kind in my whole diplomatic career. It doesn’t mean I didn’t face any difficulties during my professional past. Every day, women ambassadors and diplomats in general are confronted with a lot of challenges and unusual situations. I think what helps us overcome and react and solve those issues is our personal experience, our diplomatic training and also our female instincts. Women in general and women diplomats specifically have a proper way to deal with challenges. With all due respect to our male colleagues, we manage in a different way than them to smooth a tough situation and find appropriate solutions.

For young women who are thinking about starting a diplomatic career, I firmly encourage them to not hesitate and to go ahead. It will be a lot of work, but it’s enriching and fascinating. When you deal with bilateral or multilateral diplomacy, you live in an amazing world and it will widen your personal horizons. It will deepen your knowledge. Diplomats should communicate and be able to talk about all subjects. It will bring a lot of satisfaction and contribute to your personal development, but these women should know they need to make sacrifices when it comes to taking care of families and their personal life. It’s also a matter of passion and dedication. It’s demanding, but it brings a lot of satisfaction.

Diplomat magazine: In your opinion, what is the single most important women’s issue we need to address globally at this moment? Violence against women, child marriage, genital mutilation, human trafficking all come to mind. And do you have any ideas as to how to do it?

Melita Gabric (EU): I would say that the EU and its member states have been putting a lot of attention and resources in supporting women and girls worldwide. Almost one third of the total EU funding is for supporting gender equality and the empowerment of women. We have to do more and we have pledged to do more. We know women and girls are disproportionately hit by the social and economic crisis of the pandemic and this is why we decided to enforce support for gender equality in development around the world. We really do need to promote participation of women and girls in all spheres of life. We’ve seen that a lot of the ground gained for women and girls was lost during this pandemic.

One priority that I would single out is women’s economic empowerment and entrepreneurship and promoting access to finance. [They are] worthwhile goals in themselves, but they also have positive effects on other crucial issues, such as gender-based violence or reproductive health and rights. Economically independent women have a much better chance to make decisions for themselves and their families. I would also say that once women are economically empowered, this also contributes to economic growth and prosperity of society in general. Rising waters help raise all boats. We [also] need to help girls to get enrolled in school and also to stay in school despite all the challenges that have been very much exacerbated by the COVID pandemic.

Natasha Smith (Australia): I think economic empowerment is crucial to addressing all the other issues. You see that as much in Australia and Canada as you do anywhere else in the world. We’ve put women and girls at the centre of our aid program and pivoted the entire aid program to COVID response and recovery, but still with a strong focus on gender equality.

Regarding solutions: If we all had the solutions, we’d all trot off and get our Nobel Prizes. But I think education is absolutely fundamental. I have a very long development background and there is so much evidence that the most important thing you can do for someone is education. Data is also very important because what is measured gets addressed. You need the data to make the business case and [that’s] how the solution gets the votes. Nutrition is also fundamental, as are reproductive health rights. Affordable child care is important to women’s economic development and leadership. I agree entirely in terms of the No. 1 concern being how we build back fairer and make up the lost ground, particularly in terms of meeting the [United Nations] sustainable development goals because I think we’re behind. All of the things you listed are critical, but if we get economic inequality sorted, hopefully by the weekend [laughs], then I think addressing other areas becomes a lot easier.

Maria Vass-Salazar (Hungary): I couldn’t agree more. My choice for key issues in the global picture includes education, which is essential for any further progress in women’s empowerment, but I think the real challenge is how you make all these possibilities available for women in a culture that doesn’t accept these parameters. To get ownership in an environment where women learn their role from a very early age, how do you get through that barrier within the society? We should reach out, but what if it’s not safe? That’s the biggest challenge — to get leaders from within those societies to make changes.

The other issue from a different angle is the balance — how women in leadership roles need more assets so they can strike the right balance between their family life and professional life. That’s also a factor that holds women back from progressing because they can’t find a way to do both equally well.

Konstantina Athanassiadou (Greece): Under COVID, we saw that there was a rise in domestic violence and the only cases we have seen were the cases that were being reported. COVID bared many elements. The real impediment of women vis-à-vis men is the lack of equal strength and that appeared in the rise in the numbers of domestic violence [incidents] with no witnesses.

[Generally,] I would agree with what was being said on economic empowerment and programs around the world and I very much agree with whatever is being decided in the European Union because it goes to the right direction. But now we need something that is a product of extraordinary circumstances. We should have something binding on the part of progressive governments to include women’s [voices] in the decision-making on post-COVID recovery. This will create real empowerment.

Josefina Vidal (Cuba): I agree that education and empowerment are important, pressing issues, but I agree also with my Greek colleague that we have to address in a very significant way gender violence because it has become worse during the pandemic. I don’t have a magic solution to offer, because it expresses itself in different forms and in different places. For example, you have countries where physical violence is very visible, but you have others where economic violence happens, or psychological violence also exists. Those are most common in my country. We’ve been adopting measures and our new constitution gives expression not just to non-discrimination against women and [to] gender equality, but also the issue of gender violence in general.

Another issue is educational programs and media campaigns. We have a very strong emphasis on these specific issues, including violence and gender equality, in the curriculum at all levels of our educational system. [This is also happening in professional settings.]

Romy Vasquez (Panama): In my country, domestic violence has increased, but it has also become open because basically, all the women had the worst jobs. They were taking care of children, elders and working at home. They became more vulnerable. But when I talk about violence against women, I want to become disruptive. When we were making decisions, women were not taken into account and that’s another form of violence for me. We have a country where we have institutions. We have more women with degrees than men, but they are not getting the jobs, so that’s another form of violence. In terms of the question itself, when we talk about genital mutilation or child marriage, even though we don’t have those issues in my country, I think that all of those are a form of violence. The problem globally to me is that there’s a market of transactions where the product depends on acts of violence against women. Therefore, internationally, this is linked to organized crime and this becomes the most important issue to me. So this is the moment to act.

Hanne Eskjaer (Denmark): It’s very difficult to choose one topic. What my colleagues have shown is that it’s so interconnected so where do you start unravelling these systemic challenges? One thing that sifts through all our discussion is education. The lack of education — maybe not in some of the countries we represent, but on a global scale — is really one of the most crucial starting points for girls and young women and women in general in society. It’s really losing a key opportunity for a more equal future and it’s really linked to the pandemic when 250 million kids and youth didn’t have access to education. The UN has estimated that during the pandemic, 90 per cent of all kids have lost access to education. The key issue when we talk about recovery is, will the girls be allowed back? When girls aren’t going to school, the risk of them facing domestic violence, being forced into early marriage, teenage pregnancy, lack of hygiene and lack of access to one meal a day, is lost. If we can’t grasp that now, as part of the key post-pandemic recovery, we really expose our girls to a huge challenge that we will feel for generations.

What is to be done? I don’t think we get a Nobel Prize for any of the suggestions we came up with today, but we need a global response to this. We have UN organizations, UNICEF — they are asking for core funding for the programs. We need to invest in education. It doesn’t come for free. I think we have to look at our teaching methods. Digital online learning — some of it will stay, but in some countries, there’s a total lack of connectivity, so girls will face additional challenges. We need to ensure education is inclusive and equal. We are behind, but we’ve all commited to the sustainable development goal of education. We have a golden opportunity to work with Canada.

Michelle Cohen (Dominican Republic): I agree with Romy when she was saying all of those issues are mainly one, which is violence against women. My mom has worked her whole life on this topic. She had the opportunity to work with Congress so I [watched] her advocate for human rights and women’s rights specifically. It is a challenge and child marriage is still an issue. When we put together the lack of education and research, it drives families into giving away their girls to someone who can take care of them because they can’t. With lack of education from both sides, there is an abuse of power by men who put girls and women into a situation of weakness. That’s where the state has to come in with public policy to [create a more equal] society.

Michelle Cohen (Dominican Republic): I agree with Romy when she was saying all of those issues are mainly one, which is violence against women. My mom has worked her whole life on this topic. She had the opportunity to work with Congress so I [watched] her advocate for human rights and women’s rights specifically. It is a challenge and child marriage is still an issue. When we put together the lack of education and research, it drives families into giving away their girls to someone who can take care of them because they can’t. With lack of education from both sides, there is an abuse of power by men who put girls and women into a situation of weakness. That’s where the state has to come in with public policy to [create a more equal] society.

Josefina Martinez Gramuglia (Argentina): I completely agree with many of the issues, including education as a main priority. Regarding the main issues women face in Argentina, we’ve seen the struggle for equality and empowerment of women in all fields and we all acknowledge that this relates to power imbalances. It’s reasonable to say we’ve come a long way and we’re certainly on a track of change. At the same time, I have to agree with those who believe we have to augment women’s power. It’s no longer enough to advocate for women’s rights, it’s time to stand up and strengthen women’s power. The diplomatic world has its own particular challenges and bringing more women into diplomacy is a symbol of hope and modernization, but as many of my colleagues already mentioned, in Argentina, we’re also still underrepresented in senior diplomatic positions.

This is one of the main challenges we are facing. Again, it has already been mentioned, but we believe we should be included at every table where decisions are made, involved in the decision-making process to bring our perspective for better results. The feeling is that there is a need to remedy the imbalance of power that exists all around. At headquarters, only 23 per cent of high-ranked positions are held by women; of the 160 representations abroad, 26 per cent are led by women and in higher ranks of ambassadors and ministers, only 24 per cent of our diplomatic [representatives] are female. They’re not impressive numbers, but there is hope. I remember when I entered the foreign affairs institute, women were 20 per cent of my cohort and that number is now almost 40 per cent on average. More women are entering the field, more are assuming leadership roles and, in a way, breaking centuries of tradition.

We have several measures to correct this imbalance. There was the creation of the bureau for women and gender affairs, there was a decision to establish a focal point dealing with gender-based discrimination and violence at work and it’s actually working. And most important, last year, there was an express decision to appoint more women.

Hanne Eskjaer (Denmark): I think this is one of the areas where we are proud. We’ve had several women prime ministers, we’ve had several good role models so the trend is right, but the pace is way too slow. One of our main problems is that we need more women in leadership positions, where decisions are made. This is in the public sector and diplomacy, but also in the private sector and on corporate boards. In Denmark, we don’t have mandatory quotas, but a lot of people adopt them on a voluntarily basis. If you don’t have a measurable target, it’s difficult to see if you’re achieving anything. Targets are important to make a change.

In our ministry, you cannot put forward any candidates for a leadership position without women being part of it. That makes people think who is out there. We have to work on our pipeline and strategically see the young talent and nurture it with mentorship, education and programs to start early on. Then you need the systems, [such as] parental leave. How do you make it easy for fathers and partners to take their share?

Natasha Smith (Australia): I think we’re going a bit off piece from your question, so I’ll stay over in the trees with everybody else. Like Denmark, I can’t agree more on the importance of systemic change. We have seen a deliberate approach to getting more women into leadership positions. We have a strategy in our department. We are now over 40 per cent of heads of mission and we have a pipeline, but we had a problem where the pipeline seemed to break once you got to a certain level and that’s now being very deliberately looked at and we have data and regular reviews and there’s a governance process around our women and leadership strategy.

But reflecting on how a number of colleagues have said we have to work harder and be smarter, [I’d say] no. That’s actually not the solution. I think that’s how a lot of us have had to work, but that’s not how it should work and I really do think it’s fundamentally systemic change [that’s needed] and I know that’s much easier to say coming from Australia than it would be coming from many other places. But think of any women’s issue — whether it’s domestic violence, sexual assault in workplaces, gender pay gap — we have it all. No country has actually addressed all of this. From my perspective, I think the solutions have to be political, but also [approached] from a policy perspective. They’ve also got to be practical. And dare I say it — men are fundamental to the solution. I would actually like to see this panel with our male colleagues. This is with all due respect to my very dear colleagues here, but women talking about gender equality isn’t going to fix gender equality. Of course, we’re part of it, but we need to have our male colleagues and hear what they think and how they think the system can change. I think that’s partly about parental leave, but also flexible work. One of the catchphrases of the women’s movement is that we hold up half the world and I think that’s absolutely true, but we have to remember that there’s someone holding up the other side. In Australia, we have a group called the Male Champions of Change. It’s an incredibly powerful franchise now that started within government and it’s in [sports,] an area where we’ve seen real progress. Some of our best advocates against gender-based violence are sports people.

As a member of two diversity groups in our department, I also really worry that we don’t do enough to actually promote diversity writ large because we’re all fighting for the same sort of rights and representation. We all need to be working together.

Josefina Vidal (Cuba): You were asking about the situation of women in our countries. Cuba has achieved remarkable results in terms of gender equality in the last 60 years. Cuban women now play a decisive role in Cuban society. We have attained important rights like salary [parity], maternity leave for one year. And now, sexual and reproduction rights and abortion. There is a national action plan on the advancement of women. But of course, like everyone else, we face challenges, even though 67 per cent of professionals in Cuba are women, 82 per cent of teachers and professors are women, 71 per cent of health professionals, including 62 per cent of doctors are women, 53 per cent of the Cuban parliamentarians are women. [But] we still have work to do. We need more women in decision-making positions, not just in the state and government entities, but also in enterprises. We have cases of women heading huge state enterprises, but we need more women entrepreneurs and there are still manifestations of discrimination, of violence against women as a result of sexist stereotypes. We need more training, more knowledge preparation about gender issues among decision-makers and at the community level.

Michelle Cohen (Dominican Republic): This is the combined effort and active involvement of empowerment that leads communities to make our nations thrive. Even under the predominant male leadership, women are the largest group outside government responsible for driving social initiatives. In the case of Dominican Republic, we haven’t achieved numbers in parliament, government and diplomacy. We are 54 per cent of the population of the country, but we still occupy less than 10 per cent of top cabinet positions. We’ve not yet had a woman president, but we’ve had three women vice-presidents, which is a milestone for a country like ours. But it’s a pity to say that 10 per cent in the senate are women, 25 per cent in the lower chamber of Congress are women. So there is a job to do. If we haven’t been able to occupy those positions, it is because we haven’t done all we have to do. Once again, it’s about us supporting each other.

Maria Vass-Salazar (Hungary): I think we have to think about how can we — with all this experience and thoughts [on the panel] — really make an impact? I’d like to refer back to Hanne’s previous point about the global aspect of challenges that women and girls have. I think there is good momentum as the world and the largest international organizations are focusing on post-COVID recovery and there are major focuses on the economy and there’s an incredible movement to include the environment in the recovery, but I think it’s equally important to put this on the table, and very high on the agenda in post-recovery. How [do we] address the challenges that women have, particularly in the education area? There is good momentum for that and although the challenges are bigger because of the pandemic, there is an opportunity to

really make a difference without trying to force any sort of ideas. The process is only successful if it comes from within and there’s ownership. I think the post-COVID recovery effort could be a great way to channel in these ideas in meaningful ways to make a difference.

Romy Vasquez (Panama): I think all of the comments are so important because we do have these challenges. Evidently, we need to work from within, promoting women becoming leaders in their community, we need more women in politics. We need to educate everybody and we need to educate women to participate in the community so they can become part of the decision-making process. Women participating in order to generate public policies, that is breaking the ceiling, too.

Souriya Otmani (Morocco): All the issues [listed in the question] represent various forms of physical and psychological violence against women. Violence against women worries me a lot. It is something unacceptable and any civilized and respectable society should fight against it. Recent United Nations figures on violence against women are alarming and in times of lockdown, the numbers have been multiplied by 10. Government and society should work together to bring to an end violence against women. It’s not an easy task. All of us, on a daily basis, should talk to our fathers, brothers, husbands and sons and make them understand that when violence is exerted, the whole society is shaken and our family could be broken. It’s really an issue of society and it is vital. We should really do our utmost to solve this issue and bring it to an end.

There are plenty of issues and challenges that women face every day. Regarding Morocco, I’m very proud about what’s been achieved with respect to women. Mohammed the VI really believes in Moroccan women’s abilities. He’s a promoter of women’s condition. In my country, 25 years ago, having women in diplomacy wasn’t thought about. Today, Morocco is represented by 30 women ambassadors and consuls-general on a total of 105 missions. It’s a good proportion and those women are not only appointed ambassadors, but ambassadors in prestigious countries, such as the United States. We have a woman ambassador in Madrid and Ottawa. I’m not saying everything is perfect. We still have to improve our efforts in terms of diplomacy, education, health, empowerment and we should work on the patriarchal culture that is still prevailing. Moroccan women are strong.