Niger is a country of 22 million people in Africa’s Sahel — a region that stretches for thousands of miles south of the Sahara across several countries. One of the poorest countries in the world, it has for decades provided refuge to people forced to flee their homes to escape devastating violence.

The Sahel is home to one of the world’s fastest growing displacement and humanitarian crises today. Violence and insecurity have displaced 3.8 million people across the region. Food insecurity, climate-related disasters and extreme poverty exacerbate the conflicts and plunge the population further into despair.

Violence in the Sahel began after the 2011 revolution in Libya and the 2012 uprising in Mali. Non-state armed groups, such as Boko Haram, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA), organized crime syndicates and ordinary thugs now operate across the region, exploiting ethnic tensions, weak governance and widespread poverty.

On June 5, gunmen attacked the village of Solhan in Burkina Faso’s northeast near the border with Niger. Assailants stormed the village in the middle of the night and executed 138 men, women and children. Houses and the market were set ablaze. Fearing for their lives, more than 3,300 people fled to nearby villages, among them more than 2,000 children and more than 500 women. Since the beginning of the year, more than 7,000 Burkinabé have made it across the border into Niger. Recently, gunmen shot at vehicles belonging to UNHCR as well as those of its partners. Thankfully, no one was hurt.

This year, in Burkina Faso alone, 150,000 people have been internally displaced. Of those who had to flee, 84 per cent were women, who face a high risk of gender-based violence and rape. Half of the children who fled were reportedly subject to physical abuse.

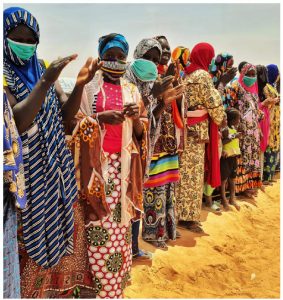

Roughly 237,000 refugees from the region have sought safety in Niger. During a visit, I saw both the cruelty — and kindness — humans are capable of.

People in Niger give what little they have to welcome newcomers into their communities. During the 2019 influx into the Maradi region of Nigerians who were fleeing widespread violence in northern Nigeria, our colleagues witnessed this generosity. People in villages along the border opened their land and even homes to refugees. In some cases Nigerien men spent nights in mosques, schools and even under the trees together with male refugees so they could leave their homes to refugee women and children. Families shared the little food they had, running the risk of not being able to make it through the lean period, “période de soudure.” Fortunately, when food distributions were carried out, host populations were included.

But Niger’s position at the centre of one of the world’s most violent regions is untenable. Its own population is no longer safe, and violence against refugees and Nigeriens alike is rising.

I met Fati Idé and her baby daughter at a UNHCR centre in Oullam. Armed groups attacked her village, which borders Mali, killing women, men and children. Idé ran to seek help from the village chief. Armed assailants later assassinated the chief. Idé managed to escape with nine other family members, including her sister, who was pregnant. Her sister went into labour as they fled, and she gave birth to stillborn twins.

Idé told me of the many rapes she had seen. She held her baby girl in her arms and said to me, “If my daughter had been a boy, the armed groups would have murdered her. They are killing all boys, even babies.”

Organizations such as UNHCR provide food, shelter and mental health support to many families. But when I looked into Idé’s vacant stare, I thought, “I don’t know if this family will ever recover.” It was one of the first times in my 25 years as a humanitarian worker that I experienced such acute doubt. In humanitarian work, we focus on hope. We share stories of the power of humans to survive, overcome and rebuild. Otherwise, why should we continue our work at all? We must have faith that things will get better or we will have no reason to go on.

Hope and despair live side by side

In one school, I saw an equal number of girls and boys studying. It shouldn’t be noteworthy, but given that most girls in Niger don’t go to school, it is, in fact, extraordinary. It reminded me of what I, and most humanitarian workers, love most about our work — seeing the impact of what we do and imagining the better future it could lead to for the people we serve.

Niger — which achieved independence in 1960 in the midst of a devastating drought — had been making progress on sustainable development goals, including improving education. But now, many gains the country made have been erased by COVID-19 and mounting insecurity. COVID-19 is, in many ways, a pandemic of poverty, amplifying and worsening existing vulnerabilities, weakening the worldwide effort to end inequality.

We know that addressing these inequalities and vulnerabilities in social, political and economic systems is key in helping the people of Niger and the Sahel have a chance at a brighter future.

This is especially true in rural areas, where a feeling of impunity and abandonment reigns. Armed groups across the region are exploiting frustrations of rural populations. Reduced education and economic opportunities are fuelling the recruitment of young men into armed and criminal groups, or pushing them towards perilous journeys to leave the Sahel. Women and girls face the threat of widespread rape and gender-based violence. Unfortunately, we have also heard about security services’ alleged involvement in very serious human rights violations, blurring the lines between being agents of protection and agents of persecution. All of this, combined with an absence of basic services, has eroded the social contract between the people and central authorities.

UNHCR and our humanitarian partners are increasingly combining emergency response with an approach that supports local authorities so they can better serve the population. This includes basic services in remote and rural areas such as schools, health services and civil documentation; inclusive political and socio-economic development with a balanced representation of the different ethnic groups; and ensuring that human rights are respected.

To do this, we need funding. Unfortunately, humanitarian programs serving the region are severely underfunded. UNHCR’s own appeal for the Sahel is only 19 per cent funded. The international community must give more. Humanitarians and local governments must also expand partnerships with development organizations, international financial institutions and regional institutions.

As a key member of the international Francophone community, and with its commitments to women’s rights and education, Canada is well placed to help expand these partnerships and mobilize increased political and financial support to the Sahel.

One way Canada can do this is through its role as a founding member of the International Organisation of La Francophonie (OIF). Established in Niger’s capital, Niamey, in 1970, the OIF represents 1 billion people on all five continents and has convened conferences on the most important issues of the day. An upcoming Summit in Djerba, Tunisia, in November could be a key moment for Canada and the OIF to make the case for increased solidarity and support for the Sahel, including Niger.

Recognized as a leader in education, Canada can also use a recently launched campaign, “Together for Learning,” to increase access to education for refugees and forcibly displaced youth — as well as the communities that have taken them in — across the Sahel.

Finally, Canada can continue leading the way in refugee resettlement, offering more spaces to refugees who want to rebuild their lives.

In Niger, I was able to see first-hand what a critical lifeline resettlement can be for refugees. At the emergency transit mechanism (ETM) that UNHCR established in partnership with Niger’s government, where refugees await resettlement, I met a mother and her two children who fled atrocities in Eritrea. Their journey took them through Sudan and then Libya, where smugglers held them captive. With help from the ETM, they were pulled out of Libya and brought to Niger so resettlement procedures could be processed.

The next day, they were flying to Halifax to start a new life.

The 19-year-old son, a huge soccer fan, couldn’t wait to live in the same country as soccer phenom Alphonso Davies — a former refugee and UNHCR goodwill ambassador who was resettled to

Canada with his family after fleeing the civil war in Liberia. The daughter, 15, could not wait to go to school.

As a mother, I’m always struck by the familiar desire young refugees have for the simple yet reassuring daily routines school and sports provide — the same routines many children in Canada crave (even if many would never admit it).

Most people in Canada, my home country, or in Europe, where I live, don’t hear these important stories of hope and despair. Yet we must continue telling them, because they are not just about the Sahel or Niger. They are human stories of people who, despite the terrible ordeal they have gone through, persevere.

That’s why I went to Niger — to draw attention to a country and a region on the precipice of a critical moment — where hope can still prevail against all odds.

Dominique Hyde is UNHCR’s global head of external relations.