“Azerbaijan — moderate, secular and with a majority of its population Muslim — lives in a tough neighbourhood. We should give whatever encouragement we can in terms of [this emerging] democracy.”

— Barry Devolin, a Conservative MP who was commenting on the merits of opening a Canadian embassy in Azerbaijan.

Preparing to vist Azerbaijan always met with the same query.

“You’re going where?”

“Azerbaijan.”

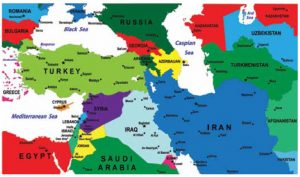

“Where exactly is it?”

“South of Russia and north of Iran.”

“Oh…. what a location!”

Many conversations about Azerbaijan start like that — people are intensely curious about a rarely mentioned (in North America, anyway) country with such controversial and pugnacious neighbours. It deserves curiosity for much more than that, though, as an ancient, fascinating and increasingly globally strategic nation.

Azerbaijan is moving into the limelight on all fronts: with pipelines and energy to a power-strapped Europe and with travellers looking for a new-but-very-old destination. It was elected to a two-year term in 2012 as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council.

Foreign Minister John Baird was to visit Azerbaijan in April. His trip was cancelled because of the death of Jim Flaherty, who had just weeks before resigned as Canada’s finance minister.

Azerbaijan is beginning to fashion itself as a world conference centre à la Dubai — rich with culture and history. The blend works wonderfully with daring modern architecture set against ancient stone buildings, and with the comfort and beautiful buildings of opulent 1800s Europe dominating the downtown of its capital city, Baku.

Azerbaijan is known as the Land of Fire for the underground natural gas pockets that are endlessly aflame. And Baku has a skyline to match. One of the most arresting sights is part of Canada’s Fairmont hotel chain — five-star in lavish interior and service — the Fairmont Baku at the Flame Towers.

The triple towers light up at night with 10,000 lightbulbs that send up alternating patterns of multi-coloured stripes or undulating flames. By daylight, the towers contrast with ancient structures, such as the 12th-Century Maiden Tower and alongside ornate 19th-Century buildings.

In the past few years, oil wealth has produced government buildings so bold in design they become tourist attractions. One such building is the State Museum of Azerbaijan Carpet and Applied Art, which carries the pattern and circular roof line of a rolled-up carpet. Then there is the white Heydar Aliyev Center, whose swooping lines, inside and out, appear as fluid as cloth. It houses auditoriums, a museum and a gallery.

Baku and its astounding skyline on the shores of the Caspian Sea recently commanded major features in no less than The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal magazines.

In June 2015, Baku will host the inaugural European Olympic Games and was one of five countries bidding on the 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics.

Mixed blessing of oil

Primarily, Azerbaijan is a petro-power. Oil has brought it both wealth and subjugation by its conquering neighbours.

With a population of 9.2 million and a GDP of $75.7 billion, it has more than tripled its per capita GDP since 1992, the first year of its independence from the USSR. According to DFATD, Azerbaijan’s 2013 per-capita GDP was $8,131. Canada exported $31.6 billion to Azerbaijan (mostly machinery, mechanical, electrical and agricultural products). Canada imported $465.3 billion from Azerbaijan (mostly oil).

One of the world’s first and oldest continuous petro-producers and pipeline builders, by the early 1900s, it was producing half of the world’s oil. The country came to international prominence when — alongside Azerbaijani entrepreneurs — Sweden’s Nobel brothers and France’s Rothschilds made a fortune and built their Baku mansions from Azerbaijani oil. (When Albert Nobel established the Nobel Prizes in 1901, he funded them with 12 percent of his share of Nobel Brothers’ Petroleum Company in Baku.)

Stalin as labour organiser

During the 20th-Century oil boom, Stalin (then Ioseb Jugashvili, the revolutionary from Georgia), plotted with Azerbaijan’s oilfield workers in taverns after their day’s work. And from Lenin’s perspective, in 1918, he said: “Soviet Russia can’t survive without Baku oil. We must assist the Baku workers in overthrowing the capitalists so they can join Russia again.”

Azerbaijan’s proven crude oil reserves, estimated at 7 billion barrels in January 2013, put the country in the top 20 largest oil exporters. But gas will catapult Azerbaijan to the forefront, given production from the Shah Deniz field in the Caspian Sea, considered one of the world’s largest gas and condensate fields.

With Russia using its gas and oil as political weaponry to back up its military influence and mobilisation, first in Georgia and now Ukraine, Europe will look increasingly to Azerbaijan and its pipelines to circumvent Russian-controlled gas, oil and pipelines.

The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline carries crude oil 1,768 kilometres from the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli oilfield in the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. It links Baku with Turkey’s Mediterranean port city of Ceyhan via Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi.

BP, the Shah Deniz operator, estimates 40 trillion cubic feet in that gas field alone, which will reach full production in 2017.

Less dependence on Russian gas

A new pipeline holds much promise for getting the Caspian Sea gas to Europe, circumventing Russia and Ukraine. The Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) will carry natural gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field to the new pipeline, which will begin in Greece, cross Albania and the Adriatic Sea and reach land in southern Italy — and beyond, to other European nations by 2018 or 2019.

Because Russia supplies an estimated 130 billion cubic metres of natural gas to Europe annually, Caspian gas will not supplant this source. It will provide Europe with 10 billion cubic metres, with an option to double that output.

As the BBC’s David Shukman put it: “With about one-third of Europe’s gas coming from Russia and about half of that gas flowing through Ukraine, these are tense times.”

While top European dependencies range widely, they are high. Virtually 100-percent-dependent countries are Finland, Slovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Romania. Poland is 80 percent dependent on Russian gas; Czech Republic at 87 percent, Hungary at 60 percent, Greece at 52 percent, Slovenia at 45 percent and Germany at 35 percent.

The other reasons to look closely at Azerbaijan:

• On a light note, but still one symbolic of its westernised culture, Azerbaijan won the Eurovision Song Contest 2011 with “Running Scared,” a love song by Eli/Nikki;

• It is a moderate Muslim country with western leanings and almost no terrorism;

• It is friendly towards the East and the West, and, more unusually (as Egypt once was), it’s a friend and partner of Israel;

• It was the first country in the Muslim world to give women the vote — (1918) one year before Canada, the U.S. or Britain;

• It was the first democratic republic in the Muslim world (1918-1920) with a European-model Parliament. No. 4 in that republic’s Charter of Rights: “The Azerbaijani Democratic Republic guarantees to all its citizens within its borders full civil and political rights, regardless of ethnic origin, religion, class, profession, or sex.”

Timeline of turmoil

In a chilling timeline of armed conflicts among Russians, Armenians, Georgians and Azerbaijanis, Fuad Akhundov, writing in Azerbaijan International 1998, gives this background on the final days of the young republic, a republic many yearn to reclaim.

“Without a doubt, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan existed during the most turbulent, unstable and complicated period of local history in the 20th Century. Ethnic conflicts and continuous wars with Armenia, aggravated by the collapse of the Russian Empire, communist coups, civil war in Russia and the consequences of World War One, brought the region of the Caucasus into complete turmoil. This, in turn, facilitated the occupation of the entire region by the Soviet Army.”

1919

May 26: The Republic of Georgia declares independence from Russia.

May 28: Azerbaijan and Armenia declare independence. Azerbaijan forms the first Cabinet of Ministers.

1920

April 27-28: 11th Red Army troops enter Baku. The Communist Party demands the resignation of the Parliament of the Azerbaijan Republic. Soviet power is declared in Baku.

May 20: The Soviet Army occupies the remainder of Azerbaijan. An uprising in Ganja is suppressed. Horrific atrocities occur when the Communists kill 40,000 [by other accounts 20,000] Azerbaijanis.

Summer-Autumn: Further dissemination of Soviet power in Azerbaijan.

December: Fall of the Republic of Armenia. Soviet regime is established in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital.

1921

February: Soviet occupation in Georgia.

1922

Dec. 22: Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia become part of the USSR.

Make a nearly 70-year leap to 1991 when Azerbaijan declared its independence after the fall of the USSR.

Many of the Soviet bloc countries struggled to fight corruption and/or the economic aftershock of losing Russian-style communism and the security it bestowed. Still, many willingly exchanged it for democracy, or more democracy, and their people made difficult sacrifices to fix their economies.

In January, the Embassy of Azerbaijan and Carleton’s University’s Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies sponsored a wide-ranging seminar on Azerbaijan.

One of the speakers was Conservative MP Barry Devolin. He chairs the Canada-Azerbaijan Inter-parliamentary Friendship Group which, in a pro-democracy initiative, has overseen exchanges between Parliamentarians. He has gone on three such visits himself.

He favours strong parliamentary ties between the two countries. “Azerbaijan is an emerging democracy with challenges in democracy, voting rights, fair elections. I think we have an interest in supporting countries [to promote] democracy, liberal law and trade.”

Azerbaijan-Canada university ties

Beyond lawmakers’ visits are educational exchanges. Last year, Baku State University and the University of Waterloo signed a memorandum of understanding allowing Baku’s mathematics and science faculties to apply to Waterloo’s faculties. And, in January, Carleton University signed a memorandum of understanding to promote academic and cultural relationships and eventually exchanges of students and professors. Today, 170 university students from Azerbaijan are in Canada under the auspices of their government’s study-abroad program.

Rashad Ibadov, assistant law professor at the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy in Baku, told the Carleton seminar that Azerbaijani (rather than Russian) has become its language of instruction. Minorities are allowed to hold classes in their own languages. And, though an unsurprising announcement in the West, he made special note that science is taught in Azerbaijan’s schools. (This contrasts with some Middle Eastern countries that favour educating children, sometimes only boys, in religion and not pursuing modern studies of math and science.)

Heydar Mirza, research fellow at the Azerbaijani government’s Center for Strategic Studies, discussed Azerbaijan’s unique relationship with Israel.

Among all post-Soviet states, Azerbaijan is Israel’s “top trade partner,” supplying more than one-third of its oil. Crucial security of pipelines has also made the U.S. and Israel allies of Azerbaijan.

Beyond that, Israel has sold Azerbaijan ground-based missile defence systems and anti-ship missiles as part of a $1.6-billion weapons package. It prompted, said Mr. Mirza, “organised hysteria” in many Iranian, Russian and Armenian media that had interpreted the purchase as directed at the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan.

Comprising 20 percent of Azerbaijan’s territory, this region in southwestern Azerbaijan has been occupied for 20 years by Armenian separatists who won some of that land in the brief 1992-1994 war and then added seven more regions to it.

This disputed region is a key issue, nationally and internationally, partly because it carries the threat of regional instability and of proxy provocations, with Russia and Iran supporting Armenia and Turkey supporting Azerbaijan.

Just in case these alliances aren’t confusing enough, Russia remains Azerbaijan’s main supplier of military equipment, even as it supplies Armenia militarily.

Rumour has it that Israel (and its ally, the U.S.) can monitor Iran’s cyberspace warfare program and provide Azerbaijan with valuable intelligence. The Israeli military deal with Azerbaijan was made partly because the U.S. and Europe have restrictions on selling weaponry to Azerbaijan, fearing it may be used against Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh if Azerbaijan’s patience to secure a settlement runs out.

A frozen conflict

Meanwhile, Iran is generally believed to be stoking the fires of separatism in Azerbaijan in the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh where Iran, Armenia and Russia support its secession. In the mid-2000s, Moscow hosted meetings with leaders of Georgia’s breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia and has met with representatives of Nagorno-Karabakh in support of their independence.

Despite the many polarising forces at work, Azerbaijan manages to keep peace with Armenia. The 1992-94 war ended with Armenian occupation, 30,000 people dead, 586,000 Azeris driven out and another 250,000 expelled from Armenia, according to Swiss journalist André Widmer in his years-long investigation that resulted in the documentary photography book, The Forgotten Conflict: Two Decades after the Nagorno-Karabakh War.

The conflict has created one million Azerbaijani refugees and internally displaced persons. The government says it is one of the largest, if not the largest, refugee populations per capita in the world.

To this day, bursts of fire across the border kill patrolling soldiers on both sides. Shelling of civilians in Azerbaijani towns regularly breaks the ceasefire, sometimes lethally. Villages and cultural landmarks have been razed during the occupation.

Mr. Widmer, who spoke at the Carleton seminar in January, said that last year alone, 20 soldiers died at the border. He went there to write a brief magazine article but spent years on research and photography because Azerbaijani refugees pleaded with him not to “let us be forgotten.” Many live in primitive conditions as they await a return to their homes, though the Azerbaijani government has embarked on a program to build new homes for them.

Meanwhile, Armenians in the rest of Azerbaijan have an uneasy existence, which international observers fear could make them vulnerable to aggression or discrimination.

Despite resolutions by the UN General Assembly calling for withdrawal of occupying forces, and affirming the inviolability of international borders and prohibition of use of force to acquire territory, the conflict remains in a frozen state.

And despite Iran’s support for Armenia, Azerbaijan engages with fear-provoking neighbours Russia and, to a much lesser degree, Iran.

For example, Iran-Azerbaijan trade rose 23 percent in 2013, to $1 billion.

That said, Azerbaijan has geographically served as a buffer for Russia from Iran and Turkey. And, to complicate matters further, Iran’s population of Azeris is large, and more than double the number of Azeris in Azerbaijan itself. A source of Iran’s concerns over separatist Azeri movements within its border, Azeri population estimates range up to 25 percent of Iran’s population, mostly in the northern region, which is adjacent to Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijan has a strategic alliance — based on economic, military and security issues — with Georgia and an alliance based on energy and pipelines with the U.S., Turkey and Israel.

As for its growth spurt, once released from Soviet rule, Azerbaijan GDP increased from $1.2 billion U.S. in 1991 to $60 billion today — largely from the multi-national development of its energy sector.

That democracy was the driving theme of the Carleton University seminar was hard to miss, as it was held in honour of Mammad Emin Rsulzade, one of the founders of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

A 10-minute historical, grainy and dramatic 1953 film (www.youtube.com/watch?v=3HLKBl6seaw) with footage from 1918 carries his voice, speaking to the world from Washington D.C. over the Voice of America. He joyfully announced the freedom and democracy of his country, finally, after generations of conquest.

The golden age of democracy lasted two years (1918-1920), ending when Russia invaded and quashed the new republic. The same film eerily shows, decades later, Joseph Stalin speaking from a lectern, calmly pouring out and sipping what looks like beer — the man responsible for extinguishing million of lives and imprisoning generations behind the Iron Curtain.

But before that, when Stalin was still one of the Allies, a little known or heralded Azerbaijan and its oilfields helped defeat Hitler.

Hitler had planned to attack Baku on Sept. 25, 1942, to deprive Russia of fuel for its tanks and planes, and to power his own conquest. In playful anticipation of his successful attack, Hitler’s staff prepared a Victory Cake. Hitler ate the piece with “Baku” written on it, while the generals shared “Caspian Sea.” A bitter winter in 1942 stalled the German troops in the North Caucasus Mountains, making Britain’s plan to blow up the oil fields unnecessary.

With the fall of the USSR, Azerbaijan once again declared freedom in 1991 and adopted its 1918 flag. It remains on decent terms with Iran and Russia. Azerbaijan declined to join Russia’s Customs Union. (Hillary Clinton, as President Barack Obama’s secretary of state in 2012, called the customs union Russia’s attempt to “re-sovietise” the countries of the former USSR. “Let’s make no mistake about it. We know what the goal is and we are trying to figure out effective ways to slow down or prevent it.”)

But Azerbaijan is equally constrained from joining NATO, however much some in the country might wish to do so.

Black January, 1990

On the streets, one rarely hears people criticise Russia despite “Black January.” On Jan. 19, 1990, 26,000 Soviet troops attacked Baku by night. The alleged provocation was “a state of emergency” that Mikhail Gorbachev signed. In the attack, the Russians killed 130 people and injured more than 700. By one account, “many citizens lay wounded or dead in the streets, hospitals and morgues of Baku. The violent confrontations and incidents lasted into February.” The Russians detained hundreds of people.

Later, it was revealed that Mr. Gorbachev had been deliberately misled by his security forces, which were trying to save the disintegrating Soviet empire. In his apology for Black January in 1995, Mr. Gorbachev called it “the biggest mistake of my political life….”

On the hill on which Baku is built, stands a memorial park, shaded by trees, that draws families who look along row after row of identical gravestones, with the machine-etched names and photos of Azerbaijanis who were killed during the Russian invasion.

Still, Russia remains very much part of the culture of Azerbaijan. Many of its citizens have “russified” their names and most speak Russian. They seem to practise their religion quietly and personally. In Baku, one sees almost no long robes or public prayer. Occasionally one spots a man saying his prayers on a prayer rug he rolls out in the corner of a small grocery store, but it’s rare. It is a western city with a Muslim heart.

One does not see terrorism, extreme Islam, extreme intolerance of any other religion but Islam, tremendous interference in government by religious figures and religious statutes in Azerbaijan.

Remarkable progress, democratic shortfalls

Azerbaijan is a weak democracy. Its president and his family are powerful. The judiciary is not independent of the executive, perverting the trial system. Elections are flawed. A number of political opponents and journalists are imprisoned. Corruption is a serious problem. There is a price for this relative calm. In the context of the region, however, this country allows freedom of religion; indeed it generally supports it.

Contrast this to some of its neighbours, where merely speaking of the Bible can bring a death sentence, adultery provokes a stoning and showing a female wrist or ankle, a flogging.

Leyla Aliyeva, director of Baku’s Center for National and International Studies, a non-governmental pro-democracy think-tank, puts it this way: “The current situation with the recent arrests and politically motivated trials does not give reasons for optimism.”

Late in 2013, she said there were 142 political prisoners and that just more than half the polls in the Oct. 9, 2013 elections were suspect. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)reported “significant problems coming in the opening, voting and counting procedures.” It reported clear indications of ballot-box stuffing in 37 polling stations and said the counting was assessed negatively in an unprecedented 58 percent of the stations observed.

In stark contrast, the Council on Europe, a regular critic of Azerbaijan, went against the general assessment by labelling the elections “free, fair and transparent.”

MP Barry Devolin notes that the country’s independence dates only to 1991. He says there are “challenges in democracy, voting rights, fair elections. What is an appropriate standard to measure it against western democracies?”

He adds: “Given the tough neighbourhood, they’ve made a remarkable transformation.”

Without question, the country is modernising rapidly. The blessing of petro manats (Azerbaijan’s manat is worth about $1.40 Canadian) does not reach equally beyond the blocks of downtown Baku’s designer stores and government buildings. Unemployment inland is likely high, though the official statistics put the national average at 6 percent, a great improvement over a short period.

The government prides itself on multiculturalism and stability because without these, economic growth will be even harder to achieve. Heydar Aliyev, the late president of Azerbaijan and father of the current president, is credited with establishing post-Soviet Azerbaijan, and with modernising and developing its resources more fully by welcoming in foreign oil companies.

Aliyev on multiculturalism

Diplomat went to Azerbaijan on an invitation from the organisers of the Third Baku International Humanitarian Forum last autumn. It was a massive undertaking, covering hundreds of speakers on multiculturalism, science, education, biology, national identity, economics and globalising mass media.

Co-sponsored by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and Russian President Vladimir Putin (who sent his representative to speak), it was a rare chance to listen to 10 Nobel Laureates sharing the stage as they described their work in economics, chemistry, physics, physiology and medicine. Another panel featured the former presidents of Estonia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Bulgaria and Serbia and the president of Turkey as speakers.

In Mr. Aliyev’s opening comments, he called Azerbaijan “the most rapidly developing country in the world in economic terms.” He acknowledged, though, that natural resources cannot take the place of humanitarian development, which he labelled his government’s top priority.

He championed the “relatively new concept” of multiculturalism. “But we in Azerbaijan have lived in an atmosphere of multiculturalism for centuries. Multiculturalism has great traditions, not only in Azerbaijan, but also in many countries and neighbouring states. So I think it is inappropriate and harmful to question multiculturalism or talk about its failure now because there is no alternative to multiculturalism. The alternative to multiculturalism is self-isolation.”

Neither Azerbaijan nor Russia is closely associated with humanitarianism, partly because of a democratic deficit, limits on free speech and expression and because of corruption. In 2009, a referendum in Azerbaijan eliminated term limits on its presidents.

For all that, despite the West’s ability to do business — a lot of business — with regimes such as Russia and China and other undemocratic countries, it is often critical of Mr. Aliyev.

Former U.S. ambassador to Azerbaijan, Matthew Bryza, speaking just after the allegedly flawed 2013 elections in Azerbaijan, acknowledged the sharp criticism by the OSCE. He noted: “Facebook activists and journalists who call for the government’s demise are often met with confrontation.”

But he sees improvements, too. Publication of official pricing of government fees and the use of electronic payments systems “have eliminated many under-the-table payments,” to corrupt officials, he said. “Prominent businesspeople recently told me they’re suffering fewer shakedowns by customs and tax authorities.”

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index ranked Azerbaijan 127th out of 177. However, Azerbaijan ranked 46/142 in global competitiveness and 91/187 on human development or “high.” On press freedom, it ranked 162/179.

Reporters Without Borders ranks Azerbaijan as 160th out of 180 countries, with No. 1 having the most press freedom. Finland ranked No. 1 while Canada was 18th.

The former U.S. ambassador concludes: “The West has a significant strategic interest in supporting Azerbaijan’s reform efforts.” As an example, he said, less than 24 hours after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington, Azerbaijan opened its skies to U.S. military aircraft and aided in their delivery of non-lethal supplies to Afghanistan.

And while students pay for grades in some — not all — universities, he noted that the president has appointed a new “young reformer” as minister of education.

He pointed to Azerbaijan’s Shiite-majority, whose multicultural tolerance allows, among other religions, a 1,400-year-old Jewish community to “enjoy strong state support.”

He warned critics against piling on while failing to acknowledge the incredible strides the country has taken. Poverty has dropped significantly and, despite cases of fraudulent voting, the president is “popular,” he said.

Like many petro-states without democratic cultures, power resides in a ruling family or an elected official whose friends and family benefit from revenues, and who run businesses and dominate industries. Petro-wealth also provides the power and resources to rapidly modernise countries.

He concluded: “The United States and its European allies would be wise … to pursue the full range of interests and values they share with this small, but strategically significant country.”

George Friedman, chairman and founder of Stratfor, a Texas-based geopolitical intelligence firm, recently visited Azerbaijan and came away with a similar view. He characterised a current U.S.-Azerbaijan standoff by saying the U.S. won’t sell weapons to Azerbaijan “because of what it regards as violations of human rights by the Azerbaijani government. The Americans find it incomprehensible that Baku, facing Russia and Iran and needing the United States, cannot satisfy American sensibilities by avoiding repression — a change that would not threaten the regime.

“Azerbaijan’s answer is that it is precisely the threats it faces from Iran and Russia that require Baku to maintain a security state. Both countries send operatives into Azerbaijan to destabilise it. What the Americans consider dissidents, Azerbaijan sees as agents of foreign powers. Washington disputes this and continually offends Baku with its pronouncements. The Azerbaijanis, meanwhile, continually offend the Americans.”

Likewise, Azerbaijanis don’t understand how, after aiding the U.S. in Afghanistan, “risking close ties with Israel, maintaining a secular Islamic state and more, the United States not only cannot help Baku with Nagorno-Karabakh, but also insists on criticising Azerbaijan,” Mr. Friedman writes.

Russian invasion and 9/11

The recent history of Azerbaijan is a living example of why Azerbaijan is concerned about security against aggressive neighbours. Invasion and occupation often have huge blow-backs in the form of unintended consequences. Perhaps the very best example is the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

Without that Soviet invasion, there would have been no 9/11. The countdown to that attack on the U.S. started in December 1979, when the Soviets sent thousands of troops into Afghanistan to prop up the faltering Communist regime in Kabul. The U.S. and other countries armed the Afghan resistance fighters, the mujahedeen (Arabic for “those who engage in jihad”). Osama bin Laden, then 22 years old, left Saudi Arabia to join the resistance and to provide funds to Afghan mujahedeen.

The long, bloody conflict ended 10 years later when the Soviets withdrew, leaving Afghanistan in civil war. But the year before that, anticipating Russian defeat, bin Laden and his associates planned to continue jihad against the USSR. Expelled from his base in Sudan due to pressure from the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, he took al-Qaeda to Afghanistan, where he turned the country into a safe training and supply base.

From there, al-Qaeda executed its spectacular airline hijackings and crashes into New York’s World Trade Center Twin Towers and the Pentagon in Washington. The plane likely headed for the Capitol Building was heroically crashed as passengers and crew struggled with the hijackers to stop the plane from hitting its target.

Economically devastating, the warping effect of 9/11 on world finances in the hundreds of billions of dollars raised national deficits and diverted money from productive industries to defensive national security and intelligence.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan changed the world overnight. It triggered an intensified, organised bloody terrorism that has, ever since, forced the world onto uneasy alert.

Azerbaijan, on the receiving end of two Soviet invasions in this century alone, and preceded by a history of Russian imperial occupation, has broken free of that past. Looking ever westward, while keeping peace with its neighbours, Azerbaijan is carving from its ragged history an independent path to prosperity and prominence.

Donna Jacobs is Diplomat’s publisher