Many Canadians today see our diverse population as a source of pride and strength — for good reason. More than one in five Canadians were born elsewhere. That is the highest percentage of immigrants in the G7 group of large industrialized nations. Asia (including people born in the Middle East) has provided the greatest number of newcomers in recent years. Since the 1990s, Canadians — who once thought primarily of Europe when they considered events abroad — now define themselves, and the world, differently. As former prime minister Jean Chrétien said: “The Pacific is getting smaller and the Atlantic is becoming wider.”

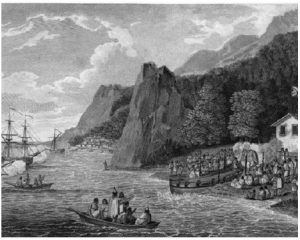

Still, the history of Asian people arriving in Canada has seen highs and lows. China is one such example. The first Chinese arrived in Canada in 1788, when about 50 settlers, who were artisans by training, accompanied Capt. John Meares. These settlers helped to build a trading post and encouraged trade in sea otter pelts between Nootka Sound (in what would become British Columbia) and Guangzhou, China. On Vancouver Island, and across B.C., the Chinese population was estimated at 7,000 people by 1860. Their numbers grew with the addition of about 15,000 Chinese labourers brought in between 1880 and 1885 to complete the B.C. section of the coast-to-coast railway line.

This also marked the start of one of this country’s darker chapters. More than 600 workers died as a result of adverse working conditions, as shown in the Heritage Minute “Nitro.” After 1885, Chinese migrants were required to pay a $50 tax to enter Canada. In 1900, Asian immigration was further restricted; the “head tax” was doubled to $100, and raised again in 1903 to $500. This was the result of complaints that were summed up by one senator, who concluded the Chinese “are not of our race and cannot become part of ourselves.” Chinese Canadians were not allowed to vote until 1947.

Arrivals from other Asian countries also faced discrimination. The first Japanese immigrants arrived in 1877. Thirty years later, Japanese migration to Canada was restricted to 400 males a year, and, in 1928, limited to 150 people annually. During the Second World War, Japanese Canadians were interned and their property was placed under “protective custody.” South Asians faced other hardships. In 1914, the government blocked the arrival of the Komagata Maru, a ship carrying would-be arrivals from India, and ordered them to be sent back. Upon their return, they clashed with British Indian police who tried to force them onto a specially commissioned train bound for Punjab. Twenty passengers died. Canada restricted immigration from South Asia to such an extent that, as late as 1961, the national census counted fewer than 7,000 people with origins in the region.

Today, many of these injustices have been corrected, and acknowledged, and the communities are thriving. In the 2011 census, South Asians, Chinese and Black Canadians accounted for 61 percent of the country’s visible minority population. They were followed by Filipinos, Latin Americans, Arabs, Southeast Asians, West Asians, Koreans and Japanese. A vivid reflection of the changing times is the four Sikh Canadians named to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s cabinet (another was born in Afghanistan). As we mark Asian Heritage Month, there is general agreement about the positive impacts these and other communities bring to Canada. At Historica Canada, we offer examples of this firsthand through the speakers who take part in our Passages Canada (passagestocanada.com) program and its accompanying video series. The Canadian population now reflects the presence of the strengths of people from around the world. As a result, Canadians feel increasingly confident about our place within it.

Anthony Wilson-Smith is president and CEO of Historica Canada.