The onset of the New Year is generally a time for punditry, predictions, crystal-ball gazing and the invariable resolutions — resolutely made, occasionally kept, more often broken.

Resolutions aside, there is good reason to be circumspect about what 2020 will bring as the year unfolds. The geopolitical order is unstable. The global economy more so. Below are just some of the more worrying trends and developments.

A slumping and more dangerous China

One of the biggest disruptions under way is China’s economic slump, which will continue into 2020. The trade war between China and the United States has taken a serious toll on China’s economy. But that is not the only reason China is recording its slowest rate of growth (hovering around 6 per cent in the third quarter of 2019, though many believe this figure is exaggerated) in almost three decades. China’s slowdown is also due to a confluence of domestic factors and policies that are hurting its economy, including a sharp decline in consumer spending and reduced public expenditure on infrastructure, which, over the years, has seen roads built to nowhere and the construction of vast cities that are empty ghost towns. Corporate profits of major Chinese firms are showing the strain. Local governments, which have borrowed heavily to finance infrastructure, are struggling to pay back their loans. For several years now, many have been predicting a debt crisis and financial disaster, especially if China’s central government is no longer in a position to underwrite these loans.

China is also paying a serious price for flouting many conventional norms of international trade and investment. Despite the pretense of a market economy, its authoritarian government has doubled down on state control of the actions of foreign and domestic business. Theft of intellectual property is chronic. Rules on foreign investment are one-sided. Many foreign investors no longer view the Chinese market as the goose that will lay the proverbial golden egg.

However, the biggest uncertainty in China is political. President Xi Jinping has demonstrated the same authoritarian, cult-of-leader tendencies as Mao Zedong and, notwithstanding his vigorous anti-corruption campaign, he is obviously not keen on political reform. Quite the opposite — he is a counter-reformer determined to consolidate his power and the Communist Party’s control over the economy. Xi’s allergy to any kind of glasnost-style opening of the political system is not unique.

China’s leaders have always worried about the dangers of political liberalization, given what happened to the Soviet Union in 1991-92. The financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 only heightened their nervousness about adapting macro-economic policies and financial systems from Western democracies to their model. China’s astronomical economic growth rates during the first decade-and-a-half of this century created a sense of confidence — some would say arrogance — that China has little to learn from the West about politics or economics. But that confidence seems to be turning into a heightened sense of paranoia with continuing domestic political unrest in Hong Kong, growing environmental protest and the prospect of major civil unrest as China’s burgeoning middle class see their own economic future dimming in a stalled economy.

It is not a rising, more confident and self-assertive China that poses a threat to regional and global stability, as some observers have argued. It is a stagnating China in which an increasingly paranoid leadership feels the need to stoke nationalist sentiments to shore up its domestic support. China’s centralized political system may be fundamentally at odds with modernity, notwithstanding all of the talk in recent years about “the Asian way.” As the American political scientist, Samuel P. Huntington, observed many years ago, economic development and the social mobilization and political awareness that come from a rapidly growing, educated, urbanized middle class is a recipe for political instability unless there are legitimate channels for political participation and safety valves to express popular grievances.

Whether Xi’s oversight of a budding personality cult and thought control by digital means can bridge this gap and provide an effective substitute for legitimate political participation remains to be seen. In the meantime, though, we may see a China that acts forcefully to quash internal dissent, takes an iron fist to Hong Kong, and continues with its sabre-rattling in the Straits of Taiwan and the South China Sea.

This is not likely to be the year for a recalibration of the U.S.-China economic relationship, either. Whether tariff battles will lead to a sensible modus vivendi or make matters worse will depend on the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. Right now, Americans are too immersed in their own internal political squabbles and leadership transition to generate the kind of deft diplomacy that is required to navigate through their major differences on trade and security issues with China, and avoid a further escalation of tensions.

Russia on the upswing

Russia under President Vladimir Putin has grandiose visions of regaining global respect and recognition similar to that once given the Soviet Union, but he is paranoid, too, as domestic opposition to his own leadership grows. With the withdrawal from Syria by the U.S., and its military drawdown in Iraq and Afghanistan, Russia will continue to fill the regional vacuum and boost Putin’s sagging popularity at home. With Russia as the Middle East kingmaker, we will see Syria’s Bashar al-Assad consolidate his murderous regime’s repressive control over the territory and borders of his country.

Russia has a massive nuclear arsenal, growing conventional military capability and tremendous capacity for mischief in and beyond its near abroad, but its economic power (Russia’s GDP is smaller than Canada’s) has diminished, notwithstanding Putin’s delusional view that he “is back at the top table, with history on his side” and his claim that liberalism has “outlived its purpose.” In 2020, Russia will keep playing its hand strategically and astutely to its own advantage, and seek to drive a further wedge into the Trans-Atlantic Alliance, which is hobbled, weak and divided.

A boiling Middle East

The Middle East remains a bubbling cauldron of insecurity. The brutal civil war in Syria spawned a global tide of refugees who have moved predominantly into Europe on a scale never before seen in history, with negative consequences for democracy in many of the receiving nations and with no consequences for al-Assad as the initiator, or for his abettors. A second flight is under way as Kurds flee Turkish forces, though that exodus, for now at least, is confined to the region.

Tension is escalating between Saudi Arabia and Iran and those tensions will rise because there is nothing to stop them. Iran has launched sophisticated attacks against oil tankers in the Gulf of Oman and against Saudi oil refineries. It also shot down a U.S. surveillance drone that it alleged had entered Iranian air space.

Iraq is slowly coming back together, but the aspirations of Iran in the region, especially its open support for terrorism, are a chronic concern for the U.S., Israel and Saudi Arabia, among others. With the American withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, there is no longer even a limited brake on Iran’s nuclear ambitions. U.S. President Donald Trump is confident that economic sanctions will bring Iran to heel, but as the economic situation there worsens with renewed sanctions, its leadership has nothing to lose by showing its open defiance of a hostile Western world by launching more attacks on tanker traffic in the Gulf and against its regional foe, Saudi Arabia. The Iranians will, as former U.S. secretary of state John Kerry observed, simply “wait Trump out,” and also secretly reignite their nuclear ambitions.

The erratic behaviour of the Saudi regime, notably the brutal murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, poses a powder keg of its own that could erupt into serious consequences for the region as greater repression by autocratic regimes, Saudi Arabia and Egypt included, lay the seeds for future rebellion and extremism.

Afghanistan was a failed state when it became a launch pad for the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the U.S. After nearly two decades, billions of dollars in economic and military assistance and thousands of deaths and serious injuries, the “graveyard of Empires” is still a quagmire for which there is no apparent solution. A Vietnam-style evacuation by the U.S. is likely in 2020, with nothing to ensure real stability for the Afghanistan’s citizenry.

Economic stagnation and social unrest in the Western hemisphere

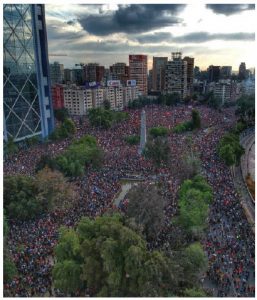

For several decades now, Latin America has been a relative pillar of stability among the world’s regions as strong economic growth, especially in major economies such as Brazil, Chile and Colombia, led to an infusion of foreign capital and the expansion of local labour markets. But many countries in the region are now experiencing economic stagnation and social unrest, which has produced its own political crisis as populists on the left and right have ascended to power. The November 2019 protests in Chile, which has been one of the region’s most successful economies and also stable politically, underscore growing frustration with the inability of the country’s political elites to address major social and economic inequalities (the third worst in the world). But Chile is not alone. Argentina, Brazil and Ecuador have all experienced similar problems, which will continue into 2020 and beyond. This may also be the year that Venezuela’s increasingly isolated dictator, President Nicolás Maduro, finally falls, but not before millions more Venezuelans flee their collapsed country, making this the world’s biggest refugee crisis after Syria.

Africa ascendant?

There has been good reason to feel bullish about the African sub-continent. Africa now represents the world’s largest free trade area with its 1.2 billion people. Although the average GDP growth rate in 2019 was just shy of 2.5 per cent, there are major differences among countries. In 2019, the fastest-growing economies in the world were Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana and Rwanda with

growth rates at or above 6 per cent. However, the region’s three biggest economies — Nigeria, Angola and South Africa — have performed poorly, largely because of falling oil prices and declining commodity prices for some precious minerals. African countries will continue to be hampered by domestic macroeconomic instability, spiralling debt, inflation, climate change, extreme drought and chronic political fragility.

Perils in cyberspace

We can expect cyberthreats to grow with the potential for more disruptive attacks on economies and society, including financial institutions and small- and medium-sized enterprises (which are ill equipped to address this challenge, unlike large firms). Many foresee the threats from cyberspace as more troubling in the year (and decade) ahead than those from terrorism or nuclear proliferation, especially given the absence of negotiated standards or an agreed rule of behaviour (i.e., codes of conduct in cyberspace.)

To riff on the observation made by the late great Italian filmmaker, Federico Fellini, “I would like to paint a more confident picture of the world…. But we are surrounded by protectionism, virulent nationalism and populism, and it is difficult to talk of other things.”

Fen Osler Hampson is Chancellor’s Professor at Carleton University. His newest book Braver Canada: Shaping Our Destiny in a Precarious World (with Derek H. Burney) will be published in February 2020.