In 2011, after a decade in the position, Gordon Campbell resigned as the Liberal premier of British Columbia. His departure followed a stunning loss of popularity resulting from his government’s introduction of the harmonized sales tax (HST). But he was ending on a high note as well — a very high one indeed. The Winter Olympics, held in Vancouver and Whistler in February 2010, were innovative in their organization, and were executed with few of the major problems, and none of the big scandals, that so often plague Olympiads. They brought Mr. Campbell praise and respect. Even the British press, so skeptical, not to say insulting, at the outset, changed its collective mind. In June 2011, Mr. Campbell was appointed Canada’s high commissioner in London. Diplomat books editor George Fetherling recently interviewed him there, at his office in Grosvenor Square. Edited excerpts of the conversation follow.

George Fetherling: Prime Minister David Cameron’s announcement that his government, assuming it wins the election in 2015, will hold a referendum on Britain’s role in the European Union was a startling one in many quarters. What was the extent of Canada’s foreknowledge of it?

Gordon Campbell: [The idea had] been a subject of ongoing discussion for some time in the United Kingdom, and certainly we anticipated there would be a referendum call from Mr. Cameron and the Conservative Party. How the Labour Party or the Liberal Democratic Party would respond was another issue. I think he crafted a very good balance by saying that he wanted to be in the European Union, that there were certainly benefits, but that he wished the British people to have a say in what the role would be. There wasn’t too much that was unexpected in his speech. I think the British need to have a discussion of the challenges they face in the European Union and the benefits they enjoy as part of the European Union. It’s important that it be a fulsome discussion. None of these decisions is without consequences. Europe itself is evolving right now, going through a significant transition phase. I think he’s saying “We’re going to protect the City and our other strengths.” In a federated union such as this, it’s important that no member thinks it’s giving up what’s most important to its own well-being in order to satisfy the group.

GF: Taken as a whole, yet giving full weight to the exceptions, the EU’s economy has been precarious for a long time. How would a dramatic further worsening of its prospects affect Canada?

GC: Hard to say. What we know right now is that Europe is going to stay together. They’re struggling with how to maintain their focus. But there are challenges [to all of us] in how things fit together as we go through this very significant period of change. Since 2008, there have been substantial changes, but there were changes going on way before 2008 that are coming to the fore.

It’s common parlance to talk about emerging markets, but typically what we mean by “emerging markets” is markets that have already emerged and are having an enormous impact on the global economy. You can’t suggest that India doesn’t have a huge impact on the world economy or that China doesn’t or that the ASEAN countries don’t. It’s a big shift away from a Eurocentric — or Atlantic-centric — world.

In British Columbia, I talked constantly about how the world had shifted to the Pacific. There’s a tendency for us to look at all the old-world structures and suddenly say they’re in a state of flux. They were always in a state of flux. Now we have all this uncertainty. For example, is there going to be a two-tier euro or a three-tier euro or a north euro and a south euro? The challenge is knowing how to deal with such big questions in open, democratic societies.

GF: One hears less than one might expect concerning Canada’s role in helping to forge a Canada-EU free trade deal: the Canadian-European Economic Trade Agreement, or CETA. One does, however, hear conflicting indications from the Harper government about the possible timetable. The so-called Doha round of talks that began in 2001 seems to have been stalled since 2008.

GC: I’m not sure the Doha talks are going to pick up momentum, but the CETA between [Canada the entire EU as a whole, with the U.K. as part of the package] is one of the most ambitious trade agreements that either side has done. It’s part of the new world, part of recognizing how much a bigger flow of people, goods and services can actually add to the various economies. So, in Canada, we’re expecting significant additional economic benefits, with thousands of new jobs and an economic lift.

If a country like Canada, so vast and so rich in human as well as natural resources, doesn’t have an open trade agreement, then our quality of life is gradually reduced. An example: B.C. itself can consume the production of only one of its many sawmills; it’s only by Canada’s being the world’s biggest exporter of softwood lumber that we maximize the benefits of our forests. Our country’s mineral and energy resources are in demand all over the world. Europe is a $17-trillion marketplace. This trade agreement will be very positive for Canada and for Europe. And, of course, we’re looking to open up trade with the Transpacific Trade Partnership as well.

If a country like Canada, so vast and so rich in human as well as natural resources, doesn’t have an open trade agreement, then our quality of life is gradually reduced. An example: B.C. itself can consume the production of only one of its many sawmills; it’s only by Canada’s being the world’s biggest exporter of softwood lumber that we maximize the benefits of our forests. Our country’s mineral and energy resources are in demand all over the world. Europe is a $17-trillion marketplace. This trade agreement will be very positive for Canada and for Europe. And, of course, we’re looking to open up trade with the Transpacific Trade Partnership as well.

As we move forward, the U.S. will be watching what’s taking place. Of course there’s been a net shrinkage in [global] trade as we went through 2008, 2009 and even into 2010. But as I look out at the square there [he points to the window] and at the American Embassy across from us, I see the trees. Right now they’re interesting natural sculptures. When spring comes, the leaves will begin to sprout and there will be different colours, and in the summertime, we’ll have a wonderful shaded area. That’s [a symbol of] the U.S.-U.K. relationship. But the roots under the ground — that’s the Canada-U.K. relationship. We’re their third-largest investor, they’re our third-largest investor. This relationship will continue to grow. There’s real interest here in Canadian enterprise.

GF: What about the Commonwealth? Many of the countries in the group are, of course, minor economic players, yet annual trade among members is $4 trillion. And whatever happened to the quaintly named Eminent Persons Group, which some of the members established in 2009 with a view toward improving the status of the Commonwealth and their own individual places within it?

GC: The Eminent Persons Group reported out, as they say, at a Commonwealth heads-of-government meeting. The overwhelming majority of their recommendations were accepted, and a new Commonwealth charter was written and signed very late in 2012. Canada is actively involved in the Commonwealth including Commonwealth reform and revitalization. You have to recognize that one of the strengths of the Commonwealth is the variety of the membership. It goes from India to St. Lucia, to take two extremes. Uniformity is not the strength. We must look for the areas where we’ll find agreement rather than disagreement. If you don’t do that, you typically discover, in today’s world, that you run out of resources before you run out of agreement.

Part of the glue that holds us together is Her Majesty and her commitment to democratic reform, human rights and the rule of law — as a foundation for economic and social development as we go forward. But there are different approaches in different parts of the Commonwealth, different approaches, such as those between the Caribbean and the South Pacific, for example, or between New Zealand and Singapore, say. I think that, potentially, the Commonwealth has a very strong role to play. Consider that we have the Rwandans asking to be a part of the Commonwealth because they see the principles on which we stand as ones on which they wish to stand as well [Rwanda joined the Commonwealth in 2009, one of only two member countries that do not have historic ties with the U.K.]

I think the Commonwealth is still an important force in the world, and Canada is both an active and engaged member, though I’m not sure that Canadians look on the Commonwealth in the same way as they used to. Senator [Hugh] Segal, who is our special envoy for the Commonwealth, is a very articulate spokesman for Canada’s place in the organization. I hope we can have more discussion of the Commonwealth in Canada because it’s a way for us to have a positive impact on, literally, hundreds of millions of people around the world. Yet the Commonwealth has a limited budget and we have to consider how we can use it to do the most good for most of the people most of the time.

GF: As you know, a large segment of the Canadian population is more than comfortable with — even delighted with — the country’s rising militarism, while another big portion mourns — perhaps even grieves over — the end of the era when our military focus was on peacekeeping. How important, or dangerous, is this division?

GC: Canada-U.K. security agreements form a very strong partnership, and Canada is an important player in security and an advocate in protecting human rights and democratic governments around the world and for helping various groups, as in Syria right now. We have to remember that when we were peacekeepers we were also putting our people in harm’s way. We’ve been in very difficult places, and our forces do Canada proud across the board. You can talk about Canadians in Afghanistan, but consider this: Are there vexing problems there? Sure there are. But there are individuals there whose lives have completely changed because of the interaction they’ve had with Canadians on the ground. We are international participants who stand on principle and do so in partnership with such countries as the United Kingdom, the United States, France and others.

GF: Canadian artists of all kinds, more and more of them each year, are acknowledged throughout the world and recognized as Canadians. But Canada has never had an equivalent of the British Council, the Alliance Française or the Japan Foundation: a not-quite-arm’s-length institution for the purpose of promoting Canadian culture and Canadian values overseas. In recent years, there have actually been severe cuts in such individual programs as did exist for something like this purpose. Why doesn’t Canada do more cultural outreach, what I sometimes like to call “cultural peacekeeping”?

GC: During the London Olympics there were 24,000 people coming through Canada House for sports and cultural activities. The first major event I went to as a diplomat was a show of the Group of Seven at the Dulwich Picture Gallery — pictures that hadn’t been here for 95 years, a phenomenal show, hugely successful; people loved it. Now there’s talk of a big Emily Carr exhibition. The other night at Canada House, we had a great evening with Margaret Atwood speaking to maybe 300 people. Then we had Michael Ondaatje come in. The ballet is coming in the spring. So we’re looking at ways of doing such things and making a place where [the artists] can be identified as Canadian. As high commissioner here, I’d like us to be [culturally] assertive, but not aggressive; confident, but not cocky. We’re Canadians. I used to be an elected official, as you know. [Smiles shyly.] When you’re elected there’s no end of people who come to you and say, “With my brains and the government’s money we can do great things.” [Laughs.] I think we should go to the artists and say, “What can we do for you?” I think that our culture defines us.

GF: So, in effect, the Canadian government isn’t sending Canadian culture out into the world so much as it is asking the world to come see for themselves, at such places as Canada House in Trafalgar Square — which a previous government seriously considered selling off.

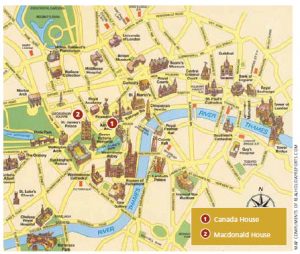

GC: Roy MacLaren, who was high commissioner in the late ’90s, is really the one [who prevented Canada House from being closed]. He did everyone a great service. Canada House is the best diplomatic address in the world, right in the heart of one of the great international cities, perhaps the greatest. It’s a fabulous piece of real estate but, more importantly, it’s a place that Canadians think of as home. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve had Canadians tell me, “Oh, I met my future husband there!” It’s “Canada House” this and “Canada House” that. Its presence, its proximity to Whitehall and Westminster, are exceptional. It’s across from the National Gallery and at the other end of the street is Buckingham Palace. It’s the second-oldest property in Trafalgar Square, after St. Martin-in-the-Field. It’s a huge asset that you couldn’t put a price on.

GF: Since the earliest days of the American republic, the most important U.S. diplomatic posting has been that of ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. For at least a century and probably much longer, the most important posting in the foreign office in Whitehall has been the position of British ambassador in Washington. Thus, Canada makes up the third side of a great diplomatic triangle. But because the triangle is an isosceles one rather than an equilateral, many people who should know better have only a foggy idea of what Canada’s high commissioner in London actually does. On an imaginary pie chart, how do you divide your time?

GC: It’s probably easier for me to think of an ordinary week or month. We try to have an ongoing, consistent voice on Europe. We work on things that raise Canada’s head. We’re about to take on the chair of the Arctic Council, for example. I would say that about 50 percent of my time concerns commercial partnerships, investments, those sorts of things. Then, obviously, there are international [political] issues that show up; I’m occasionally part of those. Then there’s welcoming Canadians. One of the things I say to people is: “You’re already paying my salary, you might as well tell me what to do.” We have an immense network of Canadians living throughout the United Kingdom. Many, many young people.

When I became high commissioner, I thought I’d lie low for a while and learn how things fit together. After a couple of months, I thought: “I know what I want to do. I want Canada to be out there, to be more recognizable.” Later, I learned that every high commissioner who’s ever been here has said exactly the same thing!

George Fetherling’s book, The Writing Life: Journals 1975-2005, was published in April by McGill-Queen’s University Press.