Vietnamese Ambassador To Anh Dung and his wife, Tran Phi Nga, meet photographer Dyanne Wilson and me at the door of their Glebe home. Ms Tran is wearing a traditional hand-painted silk Ao Dai, a national dress that bears a slight to the exterior of their heritage house whose architecture is Spanish. But inside, the house is filled with a sense of Vietnam.

The Powell House, as it is known, although it’s not on the nearby street of the same name, is immediately recognisable on Glebe Avenue. A two-storey, white stucco mansion that backs ever so gracefully onto the grassy lawns of Central Park and overlooks the end of Patterson Creek, it was deemed by the city as the best example of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture in Ottawa and was officially recognised for its heritage value in 2004.

The landmark is located in what was known as Clemow Estate and was developed around 1912 by the landowner, Henrietta Clemow, and her husband, William Powell. Their plan was to cash in on the popular trend of the day as members of the middle class began to move out of the urban core and into the suburbs. The couple hired the prolific and well-known architect, W.E. Noffke, to build their 22-room home and at least 10 other stately homes in the immediate neighbourhood. Noffke had never built in the Spanish revival genre, but managed to design a distinctive and charming building with a red tile roof, overhanging eaves, detailed relief work and a porte-cochére with large buttresses that straddles the driveway.

The house was later owned by Margaret Sheahan and in 1982, it was sold to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

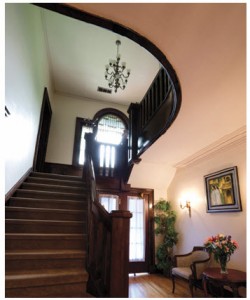

The entrance to the house is suitably impressive, opening into a large front hall that leads directly to the back of the house, where French doors open to a patio and stone steps lead down to the park. Presumably, in earlier times, boaters coming from the canal would have used this entrance.

From the central hall, a wooden staircase leads to a large landing and a tall, leaded glass window before reaching the second floor and its six bedrooms. Guests are quick to notice the star of the

entranceway: a brass drum presented to the diplomatic residence by Vietnam’s prime minister.

To the right are two reception rooms, the first decorated with formal Vietnamese lacquered wood furniture, each piece inlaid by hand with delicate mother of pearl. Ceiling mouldings echo moulding on the walls that hark back to the origins of the house. Over the fireplace sits a second brass drum, vividly engraved with symbols of Vietnam’s 4,000-year history.

The second reception room is more relaxed, with plush Victorian-style furniture and colourfully glazed pieces of pottery. Small trees and flowers adorn the rooms, many spilling out of glazed pots of different sizes and shapes.

Across the hall, the large dining room, significantly decorated with a striking lacquered mural of a Vietnamese rice harvest, welcomes those lucky enough to be invited to dine here. In the mural, women in traditional dress harvest rice in a rural village with its bamboo trees, cottages and water buffalo. The dining room is also home to three large carved figures representing important aspects of Vietnamese life; happiness, prosperity and longevity. There is also an interesting painting of the historic One-Pillar Pagoda in Hanoi.

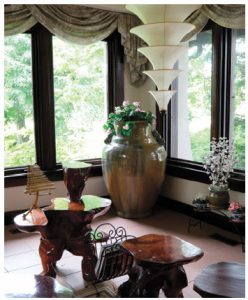

But it is the sunroom, with its magnificent view of the creek and the park where the house shows its individuality. The bright space is filled with oddly shaped chairs and a gorgeous table, all carved from solid pieces of wood. The carver has followed the natural lines of the wood creating artistic shapes from single wood stumps. A bumpkin tree from Vietnam thrives in the light. The ambassador and his wife admit they spend their happiest times in this room, enjoying the view and sharing coffee with their friends.

The family, including their 18-year-old daughter and 11-year-old son, has a Vietnamese chef, but calls in talented friends from the Vietnamese community to assist when there are large crowds. More than 400 interested visitors toured the house on a single day during this year’s Doors Open Ottawa.

“We like the house very much,” Ambassador To says. “The Spanish architecture is beautiful.” And he enjoys the short sprint to the canal for skating and the pleasure of living in a heritage house, even though he has to ask for permission to make any changes, including putting thicker glass in the windows. But little details don’t bother him much, compared to the joy of living with this architectural history. In fact, the government of Vietnam recently purchased a prestigious heritage property in New Edinburgh to use as its office.

In Vietnam, the family lives in Hanoi. They have had postings in the Philippines and Sweden, but seem content with their Spanish-Asian abode in a very cold country.

Margo Roston is Diplomat’s culture editor.