Peru, situated on the west coast of South America, sharing borders with Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia and Chile, boasts a rich multicultural cuisine combining the flavours of four continents. Dating back to pre-Inca times, an ever-evolving Peruvian cuisine has shown unique tolerance and assimilation of those cuisines introduced by immigrants from Europe, Africa and Asia. Lacking familiar homeland ingredients, immigrants creatively adapted their traditional cuisines by substituting ingredients available in Peru, resulting in something original, and now, something Peruvian.

Peru’s culinary history began 5,000 years ago when Paleo-Indian hunters and gatherers transitioned to organizing agricultural villages and started domesticating and cultivating cereals and fruits, potatoes and corn in the Andes, pumpkins and lima beans on the coast. They also looked to nature as their pantry. It offered a great variety of ingredients, thanks to Peru’s three major regions — the coast, mountains and jungle — plus its countless number of ecosystems and microclimates. Among the treasure trove of ingredients were spicy chili peppers, aromatic herbs, extraordinary fruits of the Amazon, fish and seafood and wild animals.

Incan civilization

By the 15th Century, the Incas who had emerged three centuries earlier, had developed an ingenious system of complex terracing and irrigation, allowing for the cultivation of produce on steep Andean slopes and in coastal river valleys. Potatoes, their principal crop, were the key ingredient in soups, stews and pachamanca, a type of underground barbecue using a mixture of meats and vegetables enveloped with leaves and cooked in a covered subterranean pit lined with hot porous stones. Leftover potatoes from the pachamanca were dried as a preservation technique and to reduce their weight for transportation. Carapulca, a potato and pork stew slow-cooked with hot chilies and peanuts, owes its unique flavour and consistency to its main ingredient, dehydrated potatoes or papa seca. First prepared by the Incas more than 500 years ago, it remains one of the oldest Peruvian dishes that is eaten to this day throughout the country, albeit transformed into a more hearty, spicy and complex version exhibiting a true blend of Incan, European and African flavours. Potatoes, probably the Incas’ principal contribution to the world, were indispensable in their diet, with 1,000 varieties domesticated before the arrival of the Spaniards. Peruvian Ambassador Marcela Lopez Bravo emphasizes that more than 4,000 varieties exist today and that genetic modifications are prohibited.

Incan cuisine also included cereals such as quinoa and maize, alpaca meat and that of a native guinea pig called cuy, fruits and an assortment of hot peppers. Quinoa, another food crucial to life and referred to as “the mother grain,” was deemed so sacred that at the time of planting, a golden implement was used to ceremoniously break the first furrow. In recent years, recognized as a gluten-free “super grain” exceptionally high in protein and fibre, quinoa has continued to experience a dramatic increase in international awareness and sales. Several kinds of peppers, including medium to hot heat aji and the fiery rocoto and herbs such as huacatay, gave a signature taste and frequently colour to boiled and roasted Incan dishes. These have continued to be a dominant and essential feature of Peruvian cuisine over the centuries.

Spanish conquest

Peru’s conquest by Spain in the 16th Century led to the introduction of ovens, new culinary techniques such as pickling and frying, plus a myriad of new ingredients including staples, among them rice, wheat and domesticated animals as well as olives, grapes and a wide variety of vegetables, fruits and spices. Their rather rapid integration into native cuisine sparked what became known as Creole cuisine. Goats, sheep, cows and chickens offered greater choices of meat beyond local alpacas, llamas and guinea pigs, wild hare and various types of fowl. New Creole cuisine blended milk and cheese into aji sauces to create dishes that have remained ubiquitous. Aji de gallina, a chili chicken, combines strips of chicken served with a creamy yellow spicy sauce prepared with yellow aji amarillo chilies, milk, cheese and bread. Papa a la huanciana, a similarly flavoured traditional vegetarian version of boiled potatoes with slightly spicy cheese sauce, is still served in many Peruvian homes and restaurants because it is inexpensive to prepare, yet yields a remarkable complexity of flavours and textures, thus making it popular with chefs and all classes of society. Spanish cuisine, having been strongly influenced by the Moorish domination of southern Spain, brought cumin and coriander, in addition to cinnamon and cloves that went into the famous Creole desserts.

African slaves arrive

The Spanish also brought African slaves to work on ranches, farms and in kitchens. They, too, infused their own touches. Peruvians enjoyed and adopted the seductive rhythms of African music, dance and the aromatic African spices and syrups with which they enhanced the original Incan corn pudding and perfected blancmanges and custards. Sugar cane also proved to be another ambrosial surprise. It added a heavenly taste to desserts and candies and elevated Peru to the largest consumer of sugar in the New World during colonial times. Convents generated a majority of these confections, thus guaranteeing the continuity of both for centuries. Even now, virtually all Peruvian desserts feature Eurocentric and African influences.

The African slaves’ skill in creating culinary combinations with ordinary inexpensive ingredients including leftovers, has produced two of the country’s finest dishes. Tacu-tacu with its many variations, basically features cooked beans and white rice mashed together with additions of onion and spices, then shaped into a thick pancake and fried. It can be a meal in itself or topped with a steak, fried banana, egg, even salad, or served as a side. Anticuchos, skewers of meat marinated in various spices and grilled, originally were made up of beef heart because the Spanish would consume the best cuts of an animal, leaving the organs for their slaves. Today, anticuchos, similar to shish kebabs, are served everywhere in Peru from high-end restaurants as appetizers to street-carts where they are slathered with a garlicky sauce. Any meat can be used, but beef heart is best, according to the ambassador.

The 19th Century saw a wave of consecutive revolutions, one inspiring the next. They included American, French and Peruvian. Soon after declaring independence in 1821, the new Peruvian government issued a degree allowing free entry of foreigners. Non-Spanish European immigration turned out to be robust, with influxes from Italy, France, Germany, England, Scotland and Scandinavian countries. The Italians and French, in particular, offered yet another twist to Peruvian cuisine.

Chinese workers

The most dramatic impact actually came later, in 1894, with the first indentured Chinese servants arriving to work on railroads, sugar and cotton plantations and in a flourishing fertilizer industry using bird excretions or guano. Although they mostly worked under harsh conditions, their contracts obliged their employers to provide, as part of their salary, certain foods including one-and-a-half pounds of rice daily as well as specially built living quarters, thus preserving Chinese culinary traditions. They imported seeds for vegetables, from snow peas to ginger, and introduced soy sauce. Once the Chinese were settled, they established small shops and restaurants. Peruvians’ initial hesitation about foreigners, who took anything that moved and cooked it, soon vanished when they developed a new appreciation for the tasty and simple dishes prepared in alleys next to central downtown markets. The Chinese techniques of sautéeing over a high flame, adding ginger, splashes of soy sauce and aji peppers to stir-fries — all made in the same pan — and serving rice with virtually everything, blended with Peruvian dishes to produce a delicious chifa or Chinese-Peruvian cuisine. Lomo saltado, a hearty stir-fry of beef, tomatoes, onions, peppers, soy sauce and fried potatoes usually served over white rice, remains a classic Peruvian example of Sino-Peruvian fusion.

Japanese immigrants

At the very end of the 19th Century, Japanese immigrants arrived to work in agriculture and trade, bringing with them the Japanese love of seafood, subtle flavours as well as a care and respect when handling food. Their subtle touches transformed Peru’s historical ceviches, which are seafood marinated in lemon juice, onion and hot peppers, and tiraditos, thinly sliced raw fish dishes similar to ceviche, but without onion, into those we know today. Also, Japanese steamed dishes and other recipes gave way to a popular nikkei or Peruvian-Japanese cuisine highlighted by fresh seafood in a country where many urban populations had traditionally been uninterested in fish. Within 50 years, that prejudice had faded as Japanese restaurants began serving a wide range of delightful seafood dishes and initiating a love of raw marinated food.

Regional cuisine

As influential as it was, Peruvian cuisine reflects more than the fusion of foreign cuisines. Each region of the country offers its own tastes, with dishes rooted in local tradition and ingredients. Coastal cuisine features fish and seafood as well as dishes made with squash, chilies, duck and goat. Besides the most popular ceviches and tiraditos, escabeche is a mouth-watering fish dish, but can be made with chicken, with additions of onion, hot peppers, prawns, cumin, hard-cooked eggs, olives and a sprinkling of cheese. A tangy seaweed called yuyo de mar, adds zip to parihuela, a much-loved bouillabaisse. Another well-liked northern coastal dish, seco de cabrito, roasted baby goat served with beans and rice, has a lamb adaptation called seco de cordero. Cau-cau, a tripe stew accompanied by rice, comes in many styles with a Creole and an Italo-Peruvian being most impressive, while whole oven-baked stuffed peppers such as rocoto relleno, can range from fiery to just tasty.

The staples of Andean cooking, corn and potatoes, are essential elements in many dishes, among them carapulca causa, in which potatoes are mashed with lemon juice, then layered with crabmeat, tuna or sardines, or, at times, with a salad of eggs, peppers, corn, sweet potatoes, cheese and olives. Also important are tamales, a type of cornmeal steamed in corn husks or banana leaves, and a potato dish covered in a spicy canned milk and cheese sauce. Indigenous animals such as alpacas and the highland delicacy, cuy, have been sources of meat for centuries.

The most typical highland food would be the aforementioned pachamanca. Frequently, guinea pigs are cooked in a pachamanca along with other meats and vegetables. Despite its tedious preparation, this tradition has gained popularity throughout Peru, particularly for celebrations, festivals and backyard gatherings.

Meat dishes feature strongly in Andean cuisine, particularly stews, including many made with alpaca and sheep. The gamut of pork dishes extends from fried pork, a breakfast favourite referred to as fritos; chicharrones, which are deep-fried pieces of pork ribs, but can also be made with chicken or fish; and lechon, which is roasted pig. Nourishing soups also figure prominently, among them one prepared with sheep’s head, corn and tripe, another being basically a colourful green potato soup with coriander, parsley, mint, cheese, eggs, onion, garlic and peppers, and a lightly spiced soup of noodles, beef heart, eggs and vegetables.

Amazonian cuisine incorporates products found in its rainforest, resulting in a true adventure in exotic dishes. Fish ranks as the main ingredient in jungle cuisine, especially the dolphin-sized paiche, the largest freshwater fish in the world, often served with yucca, hearts of palm and fried bananas. Locals hunt many species, even those classified as members of the rodent family such as majas, the favourite, which can be up to two feet long and weigh four kilograms. and sajino, a boar-like creature. Hunting large crocodile, considered a delicacy and dubbed black caiman, and a variety of land and river turtles, which were traditionally part of the jungle diet, is now prohibited by law.

Locals have other favourites, too. Juanes features chicken, turmeric-seasoned rice and other ingredients wrapped in banana leaves; tocacho con cecina is a paste of green plantain cooked underground and served with pork and sausage, and patarashca is flame-grilled fish.

Desserts

While Peru’s cuisine remains renowned for its well-seasoned savoury dishes, Peruvians also love their sweets. Although modified, many sweets have Spanish roots, such as picarones, a type of doughnut made with a silky purée of cooked local squash and sweet potatoes added to a mixture of yeast, flour and sugar and served with drizzles of molasses, and turrones, a type of nougat made with fruit syrup and anise. Alfajores, the ubiquitous sandwich cookies prevalent in all former Spanish colonies, come in a multitude of variations with an array of tempting fillings. The popularity of alfajor de trujillo, renamed the “King Kong” after the release of the movie in the 1930s, probably due to its exaggerated size, has a seductive filling combining pineapple sweets and that well-loved South American caramelized milk cream called manjar blanco in Peru. Indeed, that caramelized cream can be credited with infusing a sweet and exquisite flavour found in numerous cakes, cookies, pastries and ice cream. Peruvians also have access to an enviable assortment of fruits from bananas, pineapples, citrus fruits, custard apples and avocados to papayas, mangos, passion fruit and the orange-coloured, nutty-flavoured lucuma. Exotic ice cream made with lucuma rates as the nation’s favourite, followed by vanilla, chocolate and strawberry.

Future of Peruvian cuisine

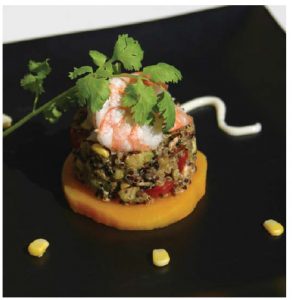

A new style of cuisine is emerging in Peru, initiated by talented avant-garde professional and amateur chefs who combine modern techniques with local raw ingredients, transforming traditional recipes into impressive new creations. Virtually unknown until recently, Peruvian cuisine is witnessing a remarkable popularity among renowned chefs and discerning palates. Please try my recipe for

Quinoa Salad Timbale. Bon Appétit! Buen

Provecho!

Quinoa Salad Stack (with Shrimp Topping)

Makes 4 servings

Salad

½ cup (125 mL) tri-coloured quinoa

1 cup (250 mL) cold water

1 tsp (5 mL) minced fresh garlic

3 grape tomatoes

½ cup (125 mL) diced* avocado

1/4 cup (60 mL) cooked fresh corn kernels

1/4 cup (60 mL) diced* fresh mushroom caps

To taste, salt and crushed black pepper

1 tsp (5 mL) soy sauce

Shrimp Topping

1/3 cup (80 mL) diced* cooked shrimp

4 cooked whole large shrimp (peeled with tails attached)

1½ tsp (8 mL) sesame oil, divided

1. To cook quinoa, rinse a couple of times in cold water and drain well; place in a medium-sized saucepan along with cold water, cover tightly and bring to a boil over high heat. Immediately reduce heat to a simmer; allow quinoa to cook until tender (10 to 12 minutes). Avoid overcooking. Remove from heat, pour into a large wire sieve and thoroughly drain off any extra liquid. Quickly transfer cooked quinoa to a large dinner plate and spread into a thin layer. Turn the hot quinoa gently with a fork to stop the cooking process, separate the grains and allow excess moisture to evaporate. Let quinoa cool and rest for at least one hour. Note: The grains of quinoa become larger, drier and firm as they cool and rest. (Makes about 1½ cups or 375 mL.)

2. To make the salad, place only 3/4 cup (180 mL) of cooked quinoa in a medium-sized bowl, sprinkle with garlic and toss. Add all remaining salad ingredients and drizzle with soy sauce; toss to combine.

3. To make the shrimp topping, place the diced shrimp and the whole shrimp in 2 separate small bowls, drizzle each with ½ tsp (2.5 mL) of sesame oil, sprinkle with salt to taste and toss.

4. To make each of 4 individual salad stacks, place a cylinder (diameter: 2 ½ inches or 6 cm) in the centre of a dinner plate; add a quarter of the quinoa salad and pack down lightly. Top each salad stack with a quarter of the diced shrimp and crown artistically with a single shrimp.

Note: If desired, build the stack on a thin round of cooked butternut squash, garnish stacks with a sprig of fresh cilantro and drizzle plates with zesty mayonnaise.

*1/4 inch or 0.6 cm cubes

Margaret Dickenson is a cookbook author, TV host, menu/recipe developer, protocol, business and etiquette instructor. (www.margaretstable.ca)