Vietnam, a long, narrow country, lies south of China, east of Laos and Cambodia and west of the South China Sea. The Vietnamese trace their origins back more than 4,000 years to the Red River Delta around Hanoi where area farmers became renowned for their rice cultivation. Beginning in the Second Century BC, the Vietnamese repeatedly had to face periodic Chinese aggression; however, in the 19th Century, Vietnam became a united state. Despite a period of humbling French colonialism and, more recently, the devastating American intervention, Vietnamese pride prevailed. Yet these intruders, particularly the Chinese and French, left an indelible mark on the food history and culture of Vietnam. Outsiders figure prominently in the country’s long history, due, in part, to its lengthy coastline. Vietnamese cuisine is an adaption to their own palates of Chinese, French, Indian and Japanese culinary traditions. Add to that mix a diverse topography, from sandy coasts and fertile highlands to forested mountains and waterlogged rice paddies.

Vietnamese Ambassador Nguyen Duc Hoa emphasizes that geography, too, plays a critical role. Vietnam can be divided into three regions — northern, central and southern — which complicates the assumption of what can be considered an overall Vietnamese cuisine. Climate in the north is difficult and its four seasons considerably limit the availability of ingredients, resulting in a major dependence on rice and the need to create recipes with a modest spectrum of ingredients. The hot weather of the south, with just a wet and a dry season, allows for a more relaxed lifestyle featuring an abundant quantity and variety of produce. Fresh ingredients all year around are key to the south’s simple and appealing cuisine.

Vietnamese cooking is one of the healthiest in the world. It’s all about freshness, locally sourced and seasonal ingredients, minimal use of dairy and oil, plus a strong reliance on vegetables and herbs.

Balance: Five flavours, five senses

The Asian principle of five elements strongly influences Vietnamese cuisine, which achieves a unique level of refined complexity through the balance of the five flavours — salty, sweet, sour, spicy and bitter — as well as an appeal to our five senses — sight, smell, taste, hearing and touch. Dealing first with the latter, the expression “we eat with our eyes” puts a focus on colourful, well-arranged food. An appeal to the senses continues with aromatic ingredients such as herbs and the blending of the flavours that linger on the palate. The crunch of crispy morsels emits sound and diners can even experience the sensation of touching food.

The saltiness from the five flavours either comes from salt or fermented seafood sources, with fish sauce being the most common and so fundamental to the cuisine that a bowl of rice simply drizzled with fish sauce might be considered as a meal in itself. The best fish sauce — virgin-pressed, like olive oil — is made from only two ingredients, small fish (usually anchovies) and salt. The ingredients are layered in wooden vats, weighted down to keep them submerged in their own liquid and stored for up to a year in a hot environment. The resulting dark brown, pungent extract, considered an “extra virgin” fish sauce called nuoc mam cot, is reserved for table use. A second extraction, where salt and water are added to the already fermented fish, produces the cooking variety. Particularly in the south, a rather foul-smelling violet paste of salted fermented shrimp, crab or various types of fish provides a salty dimension when stirred into noodle soups.

Although northerners do not typically like sweets, underlying notes of sweetness do enhance sweet and savoury dishes. Sweetness comes from sugar, sugar cane, fruit, as well as vegetables such as squash and pumpkin, which, when cooked, impart a succulent sweetness to soups, meats and seafood. The broth — or the “soul” — of the well-known classic Vietnamese soup known as pho is made of fish or meat and relies on the delightful intrinsic sweetness released from slowly boiling bones for hours.

Sweetness is counter-balanced by the sour tastes of tart fruits such as citrus fruits, tomato and seasonal dracontomelon. Fresh lime juice is added to noodle soups and dipping sauces. The juice of kasamansi, a small, green-skinned, orange-fleshed citrus fruit, mixed with salt and pepper, becomes a versatile dipping sauce for meat, seafood and omelettes. In the south, tamarind functions as the souring agent in canh chua, a fish and vegetable soup. In the north, some commercial kitchens, and to a lesser extent, home cooks, may opt to use vinegar. Sour foods typically create balance in hot, spicy dishes.

Most Vietnamese dishes call for an abundant use of fresh herbs including cilantro, basil and mint, but only a selective use of spices. Spices are regional, and with the exception of central Vietnam, dishes are generally not overly spicy. With Vietnam being a major producer and exporter of peppercorns, ground white and pungent black peppercorns season a wide spectrum of dishes from rice porridge, called chao, to beef stews. Other favourite spices include star anise and cinnamon, and mainly in the south, curry introduced by Indian traders. Curry chicken with coconut milk and lemongrass and curried beef come across as more aromatic than fiery hot.

The Vietnamese infuse bitterness with bitter cucumber, grapefruit, wild seeds and an herb referred to as knotgrass.

Rice and other staples

At the core of Vietnamese cuisine lies rice. The imperial court served rice with salt to esteemed guests. Today, locals enjoy rice once or twice every day and on special occasions, offer a bowl of rice to deceased ancestors. Rice accompanies a myriad of stir-fried meat, fish and vegetable dishes. It is fried in a wok with vegetables, eggs and other ingredients, then topped with sautéed coriander and small clams, or is broken into small pieces, then steamed and piled high with barbecued pork, an egg and cucumber, and served with a dipping sauce. In central and southern Vietnam, sticky or glutinous rice becomes a robust breakfast treat, known as xoi ngo, when served plain or combined with dried corn or pulses, but virtually always topped with a tasty sprinkling of salt, sugar, sesame seeds and crushed peanuts. Glutinous rice along with sugar and coconut milk form the basis for local sweets, or rice can be layered with pork, then wrapped in banana or bamboo leaves and steamed to create the specialty known as banh chung. The versatility of rice, once soaked and ground into flour, seems limitless. It’s used to make everything from noodles, crackers and sweets to translucent rice paper, which, when dampened, serves as a wrap for salad rolls. The ambassador points out that during troubled times, struggling citizens also relied on sweet potatoes and casava.

Vietnamese people love noodles and eat them daily, sometimes at every meal and even as a snack. Types vary, with rice, wheat, mung bean and egg being the most common. They come in different shapes, thicknesses, textures and colours. Although many noodle dishes, such as pho, are ubiquitous throughout Vietnam, regional specialties exist. Besides pho and other dishes, the northern area can rightly sing its own praises for its bun cha, barbecued sliced pork or pork patties served with vermicelli rice noodles, and banh cuoh, freshly made and steamed noodle sheets which are then stuffed with a filling of seasoned ground pork, mushrooms and shallots. Central Vietnam remains renowned for its cao lau, an exquisitely light and complex dish featuring coarse, dense-textured noodles made from a labour-intensive dough. The process involves grinding broken rice into a powder, soaking it in tap water spiked with lye water coming from certain local wells that are naturally infused with tree ash. The resulting noodles have a muddy brown colour and a subtle, smoky taste. Once cooked, these noodles are dowsed with a bit of robustly flavoured sauce, then crowned with slices of stewed pork, blanched bean sprouts, fresh greens and herbs and crunchy croutons of the same dough.

Southerners take pride in bun mam, a robust steamed rice vermicelli soup loaded with bold and clashing colours, flavours and textures — pungent, fishy, sweet, sour, dark, velvety and crunchy — all competing to dominate the palate. Often referred to as “Mekong in a bowl,” its main elements include rice noodles in a fish-paste broth, greens and pieces of bac ha, the fleshy, very thick stem of the taro plant with a web-like structure that traps the broth, offering an experience similar to that of bread dipped in soup. Two noodle dishes popular across the country are mung bean starch noodles eaten with steamed fish or stir-fried with crab meat, and very thin rice flour noodles, shaped into rather fragile nests that are rolled into salad leaves along with grilled meat. The Vietnamese also add Chinese-style noodles to soups or fry them before topping with a stir-fry of seafood, meat and vegetables in a gravy-like sauce.

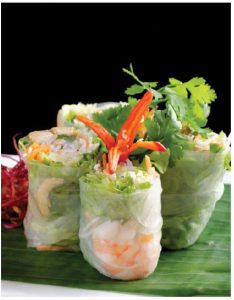

The Vietnamese wrap almost anything in translucent rice paper rolls — steamed fish, grilled meat, chicken, shrimp, pork, rice noodles, lettuce, herbs, even slices of star fruit and green banana. Types vary and include do-it-yourself rolls, deep-fried spring rolls and fresh salad rolls.

Vietnamese people particularly enjoy chicken and pork. Barbecued marinated pork can fill breakfast baguette sandwiches or it can be stacked onto broken rice. The ambassador’s wife, Nguyen Anh Thu Tran, notes that more beef is being used today than previously. It appears in pho; it can be pan-fried as steak, slow-cooked with tomato to make a stew, or skilfully wrapped in wild pepper leaves and grilled. She also says “less popular” goat tends to be eaten with beer and alcohol.

The country’s river deltas and long coastline supply an abundance of seafood and fish. Fresh-water catches include catfish, snakehead fish and small clams destined to be consumed with rice, in a broth with noodles, or simply scooped up on rice crackers. Flooded paddies provide tiny crabs. Their pulverized shells are used to make a crimson broth for a thin rice noodle dish with tomatoes, while golf ball-sized snails become part of noodle dishes such as a snail soup, called bun oc, or can be chopped with lemongrass and herbs, packed into escargot shells and steamed.

Vegetables cover the gamut from ordinary to extraordinary and include fiddleheads, water spinach and a parade of blossoms. Vietnamese people like leafy greens such as lettuce, watercress and mustard and use them in crispy pork and shrimp pancake rolls that are dipped in fish sauce. A treasure trove of fruits range from mangoes, guavas, lychees and passion fruit to the deliciously exotic mangosteen. Young jackfruit tends to be used more like a vegetable. It is often shredded, drizzled with fish sauce, sprinkled with crushed peanuts and served as a side.

The sweet stuff

Desserts and sweets are very popular, particularly during festivals. They include traditional cakes enriched with lotus and sesame seeds and peanuts, French crème caramel, ice cream, yogurts, cold sweet soups with a tapioca and coconut-milk base and shaved ice garnished with all sorts of bits and drizzles.

Meals strive to respect the concept of yin and yang by balancing food with the environment through the “heating” and “cooling” power of certain ingredients. Traditionally, a typical Vietnamese meal consists of rice or noodles, a meat or seafood dish, vegetables, soup and dipping sauces. But with today’s busy lifestyle, weekday dinners tend to be simpler affairs. All dishes are placed in the centre of the table to be shared.

Certainly, street food stalls appear everywhere in cities, offering tempting fare from charcoal-fired lemongrass and sugar cane skewers of chicken, beef and shrimp to stir-fried snails, fish in banana leaves, lotus leaf-wrapped sticky rice combinations, fried crickets and hard-boiled duck embryos.

To taste Vietnamese cuisine, please try my Quick-Skillet Barbecued Ribs.

Vietnamese Quick-Skillet Barbecued Ribs

Makes 4 servings

3 1/4 lb (1.4 kg) pork back spare ribs

2 tbsp (30 mL) brown sugar

1 2/3 tbsp (23 mL) soy sauce

1 2/3 tbsp (23 mL) fish sauce

2 tsp (10 mL) minced fresh garlic

1 tsp (5 mL) peeled and grated fresh gingerroot

1/3 tsp (2 mL) ground star anise

1/3 tsp (2 mL) five-spice powder

1 tbsp (15 mL) canola oil

Garnish

Sprigs of fresh herbs such as cilantro, mint, chives

Edible flowers (optional)

1. Remove membrane from underside of ribs by loosening a corner (at the wide end) with a sharp pairing knife. Grasp the membrane and pull gently but firmly to peel off membrane.

2. Cut ribs into single units.

3. In a small bowl, mix together brown sugar, soy sauce, fish sauce, garlic, ginger, star anise and five-spice powder.

4. Heat oil in two large heavy non-stick skillets over medium heat. Stir-fry ribs (lowering heat as necessary) until browned on all sides. Cover, reduce to lowest heat and cook for about 10 minutes.

5. Transfer ribs to a platter. Clean skillets thoroughly and return to low heat.

6. Return ribs to skillet. Pour spice mixture over ribs and cook for about five minutes, turning constantly with a silicone spatula and, if necessary, adjusting seasoning as desired.

7. Serve the barbecued ribs with rice, a papaya and mango salad (or salsa) and other accompaniments of choice; garnish with sprigs of fresh herbs.

Margaret Dickenson is a cookbook author, TV host, menu/recipe developer, protocol, business and etiquette instructor. (www.margaretstable.ca)