![The refugee crisis: ‘[We should] stabilize the hotspots so people can go back to their homes’ 1 MASSIVE1 2019 07 01 0021](https://diplomatonline.com/mag/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MASSIVE1_2019-07-01_0021-312x1024.png)

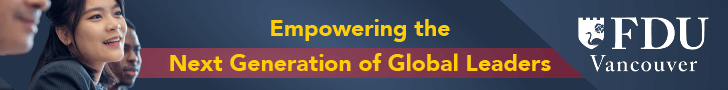

Ratna Omidvar came to Canada from Iran in 1981 and her own experiences of displacement, integration and citizen engagement have inspired her work in Canada. She was appointed by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in April 2016 as an independent senator representing Ontario. Prior to her appointment, Omidvar was the founding executive director of the think-tank Global Diversity Exchange and a distinguished visiting professor at Ryerson University. The co-author of Flight and Freedom: Stories of Escape to Canada (2015), was named by The Globe and Mail as its Nation Builder of the Decade for Citizenship in 2010 and, in 2015, she was named one of the Top 10 diversity champions worldwide on the inaugural Global Diversity List sponsored by The Economist magazine. She is a councillor on the World Refugee Council (WRC) and Diplomat’s editor, Jennifer Campbell, sat down with her to talk about a recent report by the council titled “A Call to Action: Transforming the Global Refugee System” as well as a bill she brought before the Senate.

Diplomat magazine: According to the World Refugee Council report we’re discussing today, half of the population of Syria has fled. What will become of that country?

Ratna Omidvar: It’s a very big geopolitical question. I don’t know what will happen. When I left Iran in 1980, I remember thinking that the regime change had to be coming and yet, there’s still no sign of it. In Syria, with so many [people] having been displaced and so many of them internally displaced with very little access to resources that could have been available if they’d managed to leave the country, [it’s hard to say.] I deal with what’s happening in the present.

The World Refugee Council report is a very comprehensive one and the reason it’s important is because it doesn’t present an institutional point of view of external stakeholders. It’s pretty substantive. Many of the recommendations are focused on multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations or the World Bank. But then there are a number that are in the hands of nation-states.

DM: And that brings us to the Bill S-259 — Frozen Asset Repurposing Act — you introduced in the Senate.

RO: Yes. My bill deals with a nation’s capacity to seize the assets of corrupt former officials that are located in the country and to redeploy them so the displacement that has been created by these corrupt people can be addressed and ameliorated to some extent. I tabled this bill in the Senate [in March.]

I have aspirations that Canada will embrace this idea, but I also have aspirations that if Canada embraces it, others will follow, just as Canada has followed the movement of the Magnitsky [Act, which targets the assets of corrupt officials who have committed grievous human rights violations and] which was called into law in the U.S., the U.K., Canada and Estonia. I think there’s an interest in nation-states learning from each other in how to deal with these crises of corruption and displacement because they are linked, one to the other. This is an idea whose time may well have come.

My bill is in second reading in the Senate. [Peter Beam], a former deputy minister of Global Affairs who is now a senator, weighed in last week and was very positive about what the bill is intending to do and about the approach in implementation that the bill takes. I know there are similar pieces of legislation that are being reviewed in the U.K. and France. I think the time has come to put this on the agenda. I fully intend to pick up this bill as soon as the next Parliament is convened. Peter Beam was an ambassador so he understands the global context of diplomacy in all of this.

DM: What are the other hotspots you anticipate in this context?

RO: I anticipate that Bangladesh will continue to be a hotspot because the situation in Myanmar doesn’t seem to be easily resolvable. Bangladesh is incredibly pressured with the arrival of close to a million refugees and is [buckling] under the pressure. As a result, since the world is unable to resolve the situation, they’re [Bangladesh] actually considering repatriating the refugees back to Myanmar under the very same conditions [they left] with no guarantees for their security. I imagine that hotspot will dominate the discourse for another couple of years at least.

The situation in Syria — I can’t read the tea leaves, but if I were outside Syria as a refugee, I don’t know whether I would consider going back at this point. Because ultimately, if the situations resolve themselves, then people go back. Let’s consider the history of the movement from Bosnia and Serbia in the 1990s. Canada received a number of refugees — I think it was 3,000 to 4,000. As soon as the situation stabilized with the help of the multinationals, many of the refugees left. They chose to go back and lead their lives again.

Ideally, those are the conditions the world should try to create. Stabilize the hotspots so people can go back to their homes, their language, their family, their culture and pick up the threads of their lives again. The intention of the world on resettlement, which involves about 10 per cent of the world’s refugee population, is important, but misplaced. What is more important is resolving the situations in these unstable countries. That is long-term and painful and it requires dedication and effort that is hard to sustain. We need to look at out-of-the-box solutions. The report the World Refugee Council has tabled includes a number of practical solutions that are catalytic and transformational. The bill I’m proposing is practical because it’s in the hands of one nation-state. Multilateral solutions typically are, as you well know, three steps forward, two steps back.

I do like the idea of calling into play the world’s multilateral solutions around this question of safety and security for refugees. Of course, the UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] will always be the primary multilateral institution, but there’s the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, too. When you think about all the levers that are in play and if these institutions got together and worked together as opposed to working in isolation, we could actually make some significant headway.

DM: As an immigrant, what are your thoughts on the “not welcome” signs greeting some of our refugees in Canada?

RO: It makes me unhappy, but I also understand that Canadians feel insecure when they see people cross our borders by boat or by land. They feel insecure and I believe that the insecurity has to be addressed in other ways than putting up a ‘you are not welcome’ sign. The right thing to do is to process asylum-seekers according to the laws that we have signed on to, quickly and efficiently and accept or remove them. That would give the Canadian people confidence in the system. But the system that surrounds the hearings of asylum-seekers has been deprived of resources for so long. To turn it around quickly is actually quite difficult.

I believe the changes and resources being invested in the Immigration Refugee Board are beginning [to take effect] — though not as quickly as Canadians expect and hope. I think there’s a problem [in that people are feeling insecure], but there’s also a solution and that doesn’t start with putting up ‘unwelcome’ signs.

![The refugee crisis: ‘[We should] stabilize the hotspots so people can go back to their homes’ 2 Omidvar: 'The right thing to do is process asylum-seekers according to the laws that we have signed on to, quickly and efficiently, and accept or remove them.'](https://diplomatonline.com/mag/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MASSIVE1_2019-07-01_0023-254x300.png)

DM: A 2018 poll conducted by the Angus Reid Institute found that 67 per cent of Canadians believe the refugee situation is now a crisis; and 71 per cent think there should be a greater investment in border security than on helping those who are illegally entering Canada from the U.S. outside of official border crossings. What is the solution you’d propose?

RO: I went to the border last year in June. I spent a day at Roxsom Road. I needed to touch it and feel it for myself. I had meetings with the RCMP, Canada Border Services Agency [CBSA] and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada [IRCC.] I stood and watched a number of families arriving in that ditch at Roxsom Road. I saw how they were received and processed. I’d like Canadians to know that our system and the agencies around that system have really geared up to be efficient, to follow the rule of law as it is and implement it as best they can.

I was fairly impressed. I do believe the system may come under pressure again if the numbers over the summer rise. We haven’t seen that yet, but I think we are prepared to some extent, but if there are thousands of people, that presents a problem to us. The state of readiness is fairly [well in place] at the border. Where we seem to fall down is making sure that, upon arrival, asylum-seekers get a hearing as quickly as possible. The delays in hearings and appeals and all the legal processes present a problem. I think efficiency, speed and fairness can co-exist.

A former deputy minister of immigration tabled a report on the inland asylum-seeker system and recommended a collaboration and co-ordination between the RCMP, CBSA and the IRCC, which hasn’t happened to date. There was a file done one way by the RCMP, another way by CBSA and yet another way by IRCC. You can imagine the delays and confusion and repetition of steps and processes. I know this sounds boring, but process and efficiency of process are important. Changes the IRB [Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada] has announced, for example, would allow that if there’s an asylum-seeker coming from a country where the rates of acceptance are really high, we don’t have to go through the whole process again. Instead, we do a paper review. By the same token, if the rates of rejection are really, really high, there’s no reason to roll out the whole articulated process. They always have access to an appeal. These changes are very recent and we need some time to ensure they are implemented and evaluated.

Our system is the gold standard of the world in terms of inland approvals; it is not the gold standard in Canadians’ eyes in terms of speed and efficiency. Speed and efficiency only come from adequate resources and constantly fine-tuning and improving how people are being processed. We’ve also had a debilitating shortage of IRB judges, but those vacancies have now been filled.

DM: How should the Safe Third Country Rule be changed? Refugee claimants are choosing to cross from the U.S. illegally, between entry points, jumping queues by lawful applicants and Canada is asking for the Safe Third Country Rule to be renegotiated with U.S. so that illegal entrants are not automatically entitled to a hearing. Do you agree with that?

RO: I think we have to explore a way forward and I’m not sure whether closing off access or opening it up is the most desirable. I welcome this conversation. I’m not a member of the government and have no way of knowing what’s on the table, but I think it’s important action for this government to take.

DM: What effect are populist politicians or those who want to limit migrant numbers or insist on legal applications having on this crisis?

RO: I think migration is at the heart of the rise of populism, its nativist attitudes and an aggrieved sense of being left behind — as we’ve seen south of the border and maybe in Canada as well. There is a sense of blaming migration for all the ills that may beset an individual or a community. But migration has always been a fact of life and will always be a fact of life. Refugees and asylum-seekers are conflated in this whole construct because in Canada, refugees are a very small portion of our annual immigration intake. For the most part, our immigration process works really well. We pick and choose and carefully select our immigrants. We also carefully pick our refugees, whether we select them from overseas or we select them from their asylum claims, there is a very full, articulated process that we have the luxury of enjoying. Other countries don’t necessarily have this because of their geographic locations. The populism threat to progressive liberal policies is real and in this country, it’s not refugees, it’s asylum-seekers who are at the heart of this. We have to see in the next six months how social media play this up.

![The refugee crisis: ‘[We should] stabilize the hotspots so people can go back to their homes’ 3 A Rohingya family at Kutupalong Rohingya Refugee Camp in Bangladesh. Omidvar anticipates the plight of the Rohingya will continue to be a global issue for years to come. (Photo: UN photo)](https://diplomatonline.com/mag/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MASSIVE1_2019-07-01_0024-300x243.png)

DM: How can WRC make sure protection of refugees is compatible with social cohesion?

RO: If you’re a global citizen, you understand, as [former UN Special Representative for International Migration] Peter Sutherland has said, that proximity is not the issue. Just because something is far away, doesn’t mean it doesn’t touch us. It does touch us. Look at the conversation we just had around asylum-seekers. What’s happening in Venezuela will affect us — maybe six months down the road. There’s a social cohesion element in looking after your neighbour, even if that neighbour is many oceans away.

There’s another element of social cohesion: When refugees arrive, whether in Bangladesh or in Canada, their presence in communities can be a factor that, in the beginning, is possibly disruptive, but in the long term, it makes sense to build a social cohesion in the room. I think about Jordan and the millions of Syrian refugees there. New economies are being created both by local Jordanians and Syrian refugees. Obviously, some of the Syrians will go back to Syria eventually, but there’s also hope that these regional economies will continue to grow and flourish.

DM: The report talks about economies that are cropping up in host countries as a result of businesses launched by refugees. It’s not all bad news.

RO: It’s not. It requires intention and the attention of multilateral institutes and their ability to make special concessions or waive rules such as duties here and there. These are all tweaks that can be made and the results can be surprising. The Jordan Compact [which loosened regulatory barriers to labour markets and gave refugees access to jobs] is a very interesting first experiment that we should look at and think about replicating.

DM: More than 50 per cent of refugees are younger than 18 years old. What does their future hold and how do you convince Canada’s and other countries’ policy-makers to consider them every time?

RO: I think that is the most compelling of our findings. There are 69 million displaced people in the world. Half of them are children. Think about that number — it’s more than the population of Canada. [They’re] disaffected, disenfranchised, with little hope, at least in the short term, if not in the long term, of a sustainable life that has a foundation of education, let alone homes and food and water.

You look at the people who are in the Kakuma Refugee Camp [in Kenya]. There are two generations already in that camp. What hope do we have for those young people? It is a lost opportunity in terms of what people can contribute, but it’s also a danger. Think about large groups of disaffected young people with no hope. What do we think they’re going to do?

The world should sit up and take notice. I think [policy-makers] are notionally aware of the fact. But what are we doing about it? In any given year, the UNHCR is only able to meet 60 per cent of its requirements [For 2018, it required US$8.2 billion to carry out its programs, but only had US$4.2 billion in funding; 2019 looks more promising, but will still only see it realize 60 per cent of the funding it requires.] It relies on the charity and goodwill of member states and one of the most important recommendations of the World Refugee Council is that we move from a system of voluntary contributions to a system of assessed contributions. If you’re a member of the world order, or the United Nations, there are certain obligations and these assessed contributions would bring other donor countries into the fold. It would ease the stress on a few donor countries that are ponying up more and more and would make a level playing field, plus the world refugee system would finally be resourced appropriately.

If you add to that the new scheme of financing that could come from the Frozen Assets Repurposing Act, you can see good things happening. I want readers to remember that when former Libyan president Moammar Gadhafi fell, Canada had $2.2 billion of his assets in our country. We had frozen them and when a new government was [created], Canada entered into negotiations with that government. These negotiations were not open and transparent, but it is the money of the people of Libya and we should return it to them through their government. We had no transparency or accountability of what happened. For all we know, it may have been corrupted all over again. The bill I have proposed [Frozen Assets Repurposing Act S-259] will shine light on the assets. We’ll have accountability because the courts will be responsible for making the decision on whether [the assets go] back to the government of the day of that particular country or to an NGO such as UNHCR or Médecins sans Frontières or does it go to someone else?

![The refugee crisis: ‘[We should] stabilize the hotspots so people can go back to their homes’ 4 Omidvar and 16 others sponsored this family of 12 from Syria in 2015. This photo was taken when they landed in Canada. (Photo: Compliments of Ratna Omidvar)](https://diplomatonline.com/mag/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/MASSIVE1_2019-07-01_0025.png)

DM: Is the international community abandoning host communities such as Turkey, Germany and Jordan?

RO: I think the international community has come to an unfortunate realization that the Syria conundrum will not be resolved, that the Syrian government will stay in power, and therefore, many Syrians will choose not to go home. In that light, I believe that Jordan, Syria and Lebanon need special attention and assistance that they may or may not be getting. Turkey has a huge influx of funds from the EU. I’m not sure about the others. I think abandoning is too strong a word. The way forward is unclear.

DM: How invested is Canada in the World Refugee Council?

RO: Canada should be very invested in the WRC. I’m not sure how invested they are. I’ve put forward the notion that Canada is looked to internationally as the gold standard. In spite of the small numbers we deal with, we have systems and procedures and legislation and policy that are mature. They need to mature more, but we have the opportunity to do so. Canada should think about our refugee context as a best practice. We would be well advised to create a centre of excellence in Canada that the world could look at to help them develop policy and we could learn from others. To look at the internally displaced people of the world, for example, is a robust recommendation. That number is far larger [than the number of refugees.] There are about 25 million refugees, but the number of internally displaced is 42 million. We can’t seem to touch them in a robust enough manner. The place of Canada and our experience and relative success in moving things forward, make this a report that the government of Canada should not just pay attention to, but own. Maybe it will help us get a seat on the UN Security Council.

DM: Is this the same kind of initiative as the landmine treaty and are you as hopeful about it?

RO: I am very hopeful about it, if we own it and embrace it. We’re a middle power and most reasonable Canadians accept that fact. Our greatest moments internationally are when we have taken a leap in leadership. I think of the leap in leadership prime minister Brian Mulroney took when he persuaded the international world order to work on the apartheid problem, and I think about the Land Mines Treaty and Lloyd Axworthy. It’s such a natural jump. The work we’re doing with the Lima Group [a group of countries, including Canada, that is pressing for democracy in Venezuela and recognition of president of the

National Assembly Juan Guaidó over current President Nicolás Maduro and his regime] is also a leap in leadership. Our footprint can be way larger than the size of our foot.

DM: As you mentioned, there are 42 million IDPs in more than 100 countries. How can WRC help them?

RO: Unlike the UNHCR, which cannot have any impact on IDPs, we embraced their issues as very relevant to our work. We suggested a number of proposals to deal with that, especially calling for the UNHCR to take some action by naming a UN leader to [be dedicated to] to this problem. We also recognized there are more concrete measures needed to deal with women and children.

DM: Are developed nations such as the U.S. reneging on their moral responsibilities to refugees?

RO: The actions and decisions of the U.S. are discouraging. There are other nation states that follow their lead. The populism discourse that started against migrants in Brexit is like a virus spreading and infecting populations. We need to find the right immunization against it.

Every nation state should and could be doing more. There are some states that sign a cheque, but won’t accept refugees; some accept them, but have no money. The uneven ground is an issue. The World Refugee Council does call for common but differentiated responsibilities, which recognizes that there are some nation states that are able to do one thing and not others. There’s some discussion about what common and differentiation could look like. I’m going to quote one of my heroes, Peter Sutherland. He said ‘Refugees are the responsibility of the world. Proximity doesn’t define responsibility.’

The WRC has made about six recommendations specifically about IDPs. In UN parlance, a special representative of the secretary general can call all kinds of nation-states together, table reports, make recommendations. We need a special representative on IDPs. That person could call a global summit on internal displacement. We could have special attention to donor requests and tie them to IDPs. These are basic, common sense steps. But in the absence of the world accepting and recognizing that we have an IDP crisis, nothing will move forward. Symbolic and substantive action could be that the UN says this is a crisis — we need to take some action and do this beyond the scope of the current UNHCR.

DM: Syrians in Turkey have created 100,000 jobs through 6,000 businesses — that’s a good news story, isn’t it? Do you know of others?

RO: Can I tell you a story from Canada? Tareq Hadhad came from Syria and was sponsored by a group in Antigonish, N.S. He comes from a family of chocolate-makers. He decided to rebuild the family business in Antigonish. It’s called Peace by Chocolate. It has created jobs in a depressed area of our country. It’s revitalized the local economy. He’s quite an amazing man.

DM: On private sponsorship of refugees — can you share some statistics and success stories?

RO: Since we’ve had the private sponsorship agreement, which just celebrated its 40th anniversary, we’ve sponsored 327,000 refugees. This is private sponsors, it doesn’t include the government sponsorships. Here’s another one: Two million Canadians report that they have been personally involved in helping Syrian refugees come and settle in. Environics did a poll and determined that eight per cent of Canadians were sponsoring refugees and another 25 per cent knew someone who did. That means one in three Canadians is either personally involved or aware of the private sponsorship program.

DM: Do you have any personal stories you can share?

RO: I have the story of the family I sponsored. When I created Life Line Syria, I felt it was imperative for me to walk the talk so I pulled together a team of sponsors. We were 17 individuals. We decided to sponsor a family that would be hard to place. There were 12 people in all. A mother, father and the father’s two sisters, along with eight children from the ages of three to 15. They spoke no English and lived in a tent in Lebanon for four years. They were rural people. The father had experience in construction. They arrived Dec. 18, 2015, and I just heard today that they’ve bought a house in Brampton and they’ve filed their application for citizenship. At the airport when they arrived, the father, Mahmoud, came to me and said, ‘You are Ratna?’ I said I was and he said ‘Where we live?’ I said ‘Toronto’ and I could see the sigh of relief on his face. The second thing he said was ‘I go to work.’ Private sponsors become ersatz families and they find it hard to let go. We saw them intensively for the first year, but we’ve encouraged our private sponsorship to not be too intrusive now. We’ll have a celebration in August, hopefully in their new home.

DM: Are you involved in the Global Action Network for the Forcibly Displaced (GANFD?)

RO: I consider myself a member of the GANFD. There are people who are coalescing around the notion that this not just become another report on the shelf. I’m heartened by the young voices who’ve coalesced around the report. The report is written through the lens of women and children as much as it can be and I really appreciate that. It features incentives around solutions that have come up in countries we don’t think of as progressive refugee-receiving countries. Let me give you an example: Tanzania gave citizenship status to more than 200,000 Rwandan refugees. Uganda gives plots of land to refugees. The report has [outlined several interesting] regional responses to regional movements of people that we should think about in other parts of the world. Yes, the private sponsorship program is amazing, really it is. But giving citizenship to 200,000 Rwandan refugees? Who sat up and took notice of that?

DM: Can you share some top goals of the GANFD?

RO: First, these ideas need to be kept alive and implemented and we need a global action network to do that. The Global Action Network will be the platform to bring the proposals in the report to realization. It will be made up of governments and individuals who will work outside the formal intergovernmental context and could include actors such as city mayors, financial institutions and, of course, humanitarian groups and civil society organizations.

It is not easy to reduce the goals down to three, but here are my top favourites. Please note that these are my choices and are not necessarily those of the WRC.

- Bring momentum behind at least one new multilateral reform proposal contained in the WRC (for example, annual assessed contributions to the UNHCR)

- Call into life proposals that are within the jurisdiction of a nation-state (such as repurposing of frozen assets)

- Bring unusual actors to the table as outlined in the report (e.g. multilateral organizations like the IMF and WTO, or financial-sector institutions) to [act on] recommendations such as trade preferences and refugee sovereign bonds.

DM: What role can women play in this crisis?

RO: Women and children are the crisis. They bear a disproportionate share of the burden and the risk. Their voices and perspectives have been central to the development of the recommendations. The WRC believes they must be at the forefront of change through leadership positions in the Global Action Network so that solutions implemented are viewed through a gender lens.